What is Scarcity in Economics? A Beginner’s Guide to the Fundamental Economic Problem

Have you ever wanted to buy something, but didn’t have enough money? Or wished you had more time in the day to do everything on your to-do list? If so, you’ve already experienced the core concept of scarcity, even if you didn’t call it that.

In the world of economics, scarcity is not just a passing inconvenience; it’s the fundamental problem that drives almost every decision we make, from what we buy at the grocery store to how governments allocate their budgets. It’s the starting point for understanding how economies work.

This beginner’s guide will break down what scarcity means in economics, why it’s so important, and how it shapes our world.

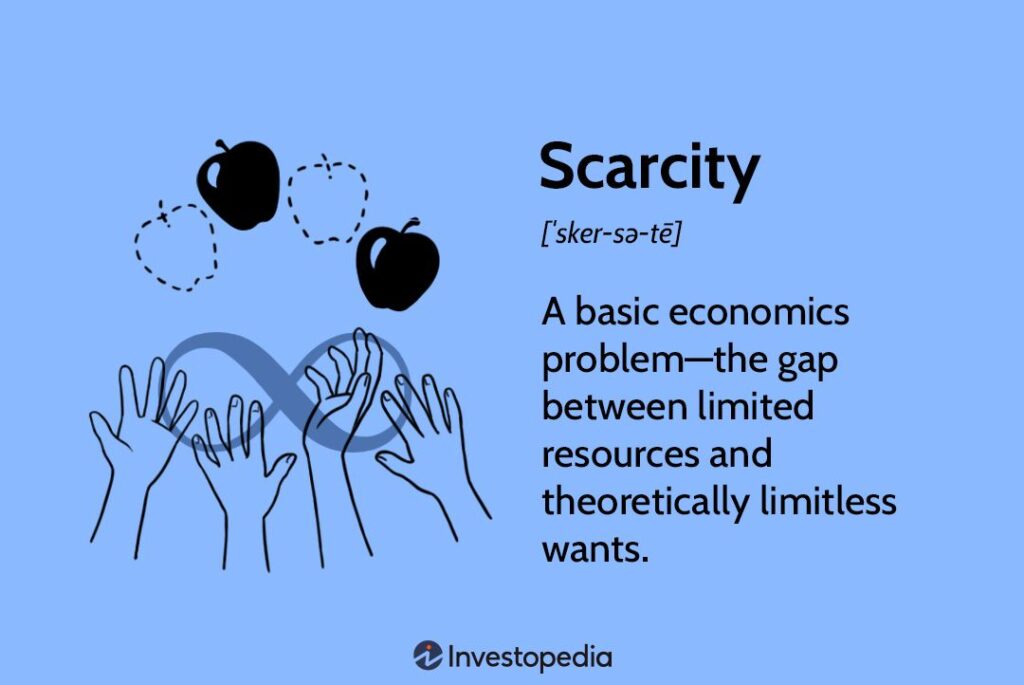

What Exactly is Scarcity? The Core Definition

At its heart, scarcity in economics means that our wants are unlimited, but the resources available to satisfy those wants are limited.

Let’s unpack that:

- Unlimited Wants: Humans, by nature, always want more. We desire better housing, more delicious food, fancier gadgets, more leisure time, advanced healthcare, a cleaner environment, safer communities, and the list goes on forever. Even if we satisfy one desire, another quickly takes its place.

- Limited Resources (or "Factors of Production"): The ingredients we need to produce goods and services are finite. We don’t have an infinite supply of land, labor, tools, or ideas.

Think of it like this: Imagine you want to bake a huge, delicious cake (unlimited want). But you only have a small amount of flour, sugar, and eggs (limited resources). You can’t bake an infinitely big cake, no matter how much you want to. You have to make choices about how big the cake will be and what ingredients you prioritize.

This gap – between our endless desires and the finite means to fulfill them – is what we call scarcity. It’s a universal problem that affects individuals, businesses, and entire nations.

Why is Scarcity So Important in Economics?

Scarcity isn’t just a minor detail; it’s the bedrock upon which all economic study is built. Here’s why:

- It Forces Choices: Because we can’t have everything we want, scarcity compels us to make decisions. Do I spend my money on a new phone or save it for a vacation? Does a country invest in education or defense? Every economic decision is a response to scarcity.

- It Creates Value: If something were infinitely available (like air, though even clean air is becoming scarce!), it would have no economic value. It’s precisely because resources are limited that they become valuable and command a price.

- It Leads to Opportunity Cost: When you make a choice due to scarcity, you give up something else. The value of that "next best alternative" that you didn’t choose is called opportunity cost. We’ll explore this more later.

- It Shapes Economic Systems: Different societies have developed different ways to deal with scarcity – from market economies (where prices guide decisions) to command economies (where governments make most decisions). All systems are fundamentally trying to answer the questions posed by scarcity.

The Three Pillars of Scarcity: Factors of Production

To understand why resources are limited, it helps to know what economists consider the fundamental "ingredients" for producing anything. These are known as the Factors of Production, and they are all inherently scarce:

-

Land (Natural Resources):

- This includes all natural resources found on or in the earth.

- Examples: Fertile land for farming, water, forests, oil, natural gas, minerals, sunlight, clean air.

- Scarcity: There’s a finite amount of arable land, clean water is dwindling in many regions, and fossil fuels are non-renewable.

-

Labor (Human Resources):

- This refers to the mental and physical effort that people put into producing goods and services.

- Examples: Farmers, factory workers, teachers, doctors, software engineers, artists.

- Scarcity: While the population grows, the availability of specific skills, health, and energy of the workforce is limited. There aren’t enough doctors for everyone who needs one, or enough skilled programmers for every tech company.

-

Capital (Man-Made Resources):

- These are man-made goods used to produce other goods and services, not consumed directly.

- Examples: Factories, machinery, tools, roads, computers, vehicles.

- Scarcity: Building new capital takes time, resources, and investment. There isn’t an unlimited supply of advanced robots or high-speed rail lines.

-

Entrepreneurship (Innovation & Risk-Taking):

- This is the special human talent that combines the other three factors of production, innovates new products or processes, and takes risks in hopes of profit.

- Examples: Steve Jobs (Apple), Elon Musk (Tesla, SpaceX), a small business owner opening a new cafe.

- Scarcity: Not everyone has the vision, courage, and ability to identify opportunities, organize resources, and bear the risks necessary to start and grow successful ventures.

Scarcity vs. Shortage: A Crucial Distinction

This is a common point of confusion for beginners. While related, scarcity and shortage are not the same thing.

-

Scarcity: This is the fundamental, permanent condition of having unlimited wants but limited resources. It always exists, regardless of price or demand. It’s like living in a desert – water is scarce because there isn’t much of it naturally available.

-

Shortage: This is a temporary condition where the quantity demanded for a good or service is greater than the quantity supplied at a given price. Shortages usually happen when prices are too low, or there’s a sudden disruption in supply. It’s a market phenomenon. It’s like a supermarket running out of your favorite brand of cereal because a delivery truck broke down – the cereal isn’t scarce in the fundamental sense, just temporarily unavailable at that store.

Key Difference: Scarcity is a constant, universal economic problem. A shortage is a temporary market imbalance that can often be resolved by adjusting prices or supply.

How Scarcity Drives Economic Decisions

Because of scarcity, every society must answer three fundamental economic questions:

-

What to Produce?

- Given limited resources, what goods and services will we prioritize? More healthcare or more education? More consumer goods or more military equipment?

- Example: A country with limited farmland might choose to grow staple crops to feed its population rather than luxury items.

-

How to Produce?

- What methods will be used to produce these goods and services? Will we use more labor or more machinery? Will we prioritize efficiency or environmental protection?

- Example: A car manufacturer must decide whether to use highly automated robots (capital-intensive) or more human workers (labor-intensive) on its assembly line.

-

For Whom to Produce?

- Who will get to consume the goods and services produced? How will they be distributed among the population? Based on income, need, effort, or something else?

- Example: A society might decide to provide free healthcare for all citizens, or only to those who can afford private insurance.

The way a society answers these questions defines its economic system (e.g., capitalism, socialism, mixed economy).

The Role of Choice and Opportunity Cost

Since scarcity forces choices, it naturally brings us to the concept of opportunity cost.

- Choice: Every decision we make, from the mundane to the monumental, involves choosing one option over others. When you decide to read this article, you’re choosing not to watch a video or cook a meal.

- Opportunity Cost: This is the value of the next best alternative that you give up when you make a choice. It’s not just the monetary cost, but what you forgo.

Examples of Opportunity Cost:

- Individual: If you have $20 and choose to buy a pizza, your opportunity cost might be the movie ticket you could have bought instead.

- Business: A company invests $1 million in a new production line. Its opportunity cost might be the new research and development project it couldn’t fund with that same money.

- Government: A government spends $1 billion on a new highway. Its opportunity cost might be the new schools or hospitals that could have been built with that same $1 billion.

Understanding opportunity cost is crucial because it helps us evaluate the true cost of our decisions, not just in terms of money, but in terms of what we sacrifice.

Scarcity in the Real World: Beyond Money

Scarcity isn’t just about how much cash is in your wallet. It affects every aspect of life:

- Time: We all have a limited 24 hours in a day. Choosing to work more means less time for leisure or family.

- Clean Water: In many parts of the world, access to clean, potable water is a severe and growing example of scarcity.

- Clean Air: Industrialization and pollution have made clean air a scarce resource in many urban areas.

- Healthcare: Medical resources (doctors, hospital beds, specialized equipment, life-saving drugs) are limited, leading to difficult choices about who receives what care.

- Education: Quality education, especially higher education, is a scarce resource requiring significant investment of time and money.

- Skilled Labor: There might be a scarcity of highly specialized workers (e.g., AI engineers, certain medical specialists) even in an economy with general unemployment.

Is Scarcity Always Bad?

While scarcity presents challenges, it’s not entirely negative. In many ways, it drives progress:

- Innovation: Scarcity encourages us to find new and more efficient ways to use our limited resources. This leads to technological advancements and creative solutions.

- Efficiency: Faced with limited resources, individuals and businesses are motivated to use what they have as productively as possible, reducing waste.

- Value Creation: Scarcity is what makes things valuable. It motivates us to work, save, and invest.

However, scarcity can also lead to conflict, inequality, and environmental degradation if not managed wisely.

Conclusion: Scarcity – The Endless Challenge

Scarcity is the bedrock of economic thought. It’s the simple yet profound truth that while human desires are limitless, the means to satisfy them are not. This fundamental imbalance forces choices, creates value, and shapes every economic decision made by individuals, businesses, and governments worldwide.

Understanding scarcity is the first step in comprehending why we pay for goods and services, why we save money, why governments tax, and why societies organize themselves the way they do. It’s a universal and permanent challenge, but one that also drives innovation and efficiency in our quest to make the most of what we have.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Scarcity in Economics

1. Is scarcity the same as shortage?

No, they are different. Scarcity is the fundamental, permanent condition of unlimited wants vs. limited resources. A shortage is a temporary market situation where demand exceeds supply at a specific price.

2. Can scarcity be eliminated?

No. As long as human wants are unlimited and resources are finite, scarcity will always exist. Technological advancements can help us use resources more efficiently or discover new ones, but they don’t eliminate the fundamental problem.

3. What are some real-world examples of scarce resources?

Beyond money, examples include time, clean water, fossil fuels, arable land, skilled labor, clean air, and even quiet spaces in crowded cities.

4. How do societies deal with scarcity?

Societies develop economic systems (like market economies, command economies, or mixed economies) to answer the fundamental questions of what to produce, how to produce, and for whom to produce, all driven by the need to manage scarcity.

5. What is the main consequence of scarcity?

The main consequence of scarcity is that it forces individuals, businesses, and governments to make choices, which inevitably leads to opportunity cost – giving up the next best alternative.

Post Comment