What is a Sovereign Wealth Fund? Unveiling Global Investment Strategies for National Prosperity

Have you ever wondered how some countries manage to save vast amounts of money for their future, often from natural resources or budget surpluses? Or how they invest these colossal sums to ensure long-term prosperity for their citizens? The answer often lies in a powerful, yet sometimes mysterious, entity known as a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF).

In an increasingly interconnected global economy, SWFs have emerged as major players, wielding immense financial power and shaping investment landscapes worldwide. For beginners, understanding these funds might seem daunting, but at their core, they are simply national piggy banks designed to secure a brighter economic future for entire nations.

This comprehensive guide will demystify Sovereign Wealth Funds, exploring what they are, why countries create them, how they invest their trillions, and their significant impact on global financial markets.

I. What Exactly is a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF)?

At its simplest, a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) is a state-owned investment fund that manages national savings for the benefit of current and future generations. Think of it as a specialized investment company, but instead of being owned by private shareholders, it’s owned and operated by a country’s government.

These funds are typically created from a variety of sources, most commonly from:

- Surpluses from natural resources (like oil, gas, or minerals).

- Excess revenues from trade or budget surpluses.

- Proceeds from privatization of state-owned assets.

- Foreign exchange reserves that exceed what’s needed for immediate economic stability.

The primary goal of an SWF is to diversify a nation’s wealth and ensure its long-term economic stability and growth, often with an investment horizon spanning decades, or even centuries.

II. Why Do Countries Create Sovereign Wealth Funds? The Driving Forces

Countries establish SWFs for a multitude of strategic economic reasons, each tailored to their unique national circumstances and long-term objectives.

-

1. Intergenerational Equity & Future Generations:

- For countries rich in non-renewable resources (like oil or gas), an SWF acts as a savings mechanism. It converts finite natural resource wealth into a diversified, sustainable financial asset base that can continue to generate income long after the resources are depleted. This ensures that future generations also benefit from today’s natural endowments.

-

2. Macroeconomic Stabilization:

- Commodity-exporting nations are vulnerable to volatile global prices. An SWF can help smooth out these fluctuations. During periods of high prices and large revenues, surpluses can be channeled into the fund, preventing the economy from overheating. During lean times, the fund can provide a buffer or be drawn upon to support government spending.

-

3. Economic Diversification:

- Many countries, especially those heavily reliant on a single industry (e.g., oil), use SWFs to diversify their national assets away from domestic economic risks. By investing globally across various asset classes, they reduce their vulnerability to local economic downturns or industry-specific shocks.

-

4. Funding Future Liabilities:

- Some SWFs are established to meet specific future financial obligations, such as national pension shortfalls or long-term infrastructure development projects. They build up reserves that can be drawn upon when these liabilities mature.

-

5. Strategic Investment & National Development:

- Certain SWFs are mandated to invest strategically in key industries, both domestically and internationally, to foster innovation, attract foreign direct investment, or secure access to critical technologies and resources that align with national development goals.

III. Where Do SWFs Get Their Money? Sources of Capital

The sheer scale of SWFs is staggering, with their combined assets estimated to be in the trillions of dollars. This immense capital comes from several primary sources:

- Commodity Export Surpluses: This is the most common source, particularly for oil-rich nations in the Middle East and Norway. When oil or gas prices are high, and production is robust, the excess revenue that isn’t needed for the national budget is funneled into the SWF.

- Non-Commodity Fiscal Surpluses: Countries with strong economies and prudent fiscal management can accumulate budget surpluses. Instead of spending or returning these funds, they can be saved and invested in an SWF to build long-term wealth. Singapore is a prime example of a nation that has built substantial SWFs from non-commodity surpluses.

- Privatization Proceeds: When governments sell off state-owned enterprises (like airlines, telecommunications companies, or utilities) to private entities, the revenue generated can be used to capitalize or expand an SWF.

- Foreign Exchange Reserves: Central banks hold foreign currency reserves to manage their country’s currency and facilitate international trade. If these reserves grow beyond what’s deemed necessary for monetary stability, the excess can be transferred to an SWF for higher, long-term returns.

IV. Global Investment Strategies: How SWFs Invest Their Billions

SWFs are known for their sophisticated and diversified investment strategies, designed to generate substantial returns over the long haul while managing risk. Unlike typical pension funds or mutual funds, SWFs often have a much longer investment horizon, sometimes stretching for decades, allowing them to ride out short-term market fluctuations.

Key aspects of their investment approach include:

-

1. Diversification is King:

- SWFs rarely put all their eggs in one basket. They spread their investments across a wide range of asset classes, geographies, and industries to minimize risk and maximize potential returns.

-

2. A Broad Spectrum of Asset Classes:

- Public Equities (Stocks): Investing in shares of publicly traded companies around the world. This is often a significant portion of an SWF’s portfolio, offering growth potential.

- Fixed Income (Bonds): Purchasing government bonds (like U.S. Treasuries) or corporate bonds. These are generally considered lower-risk investments that provide steady income.

- Real Estate: Acquiring properties globally, including office buildings, shopping malls, hotels, and residential complexes. SWFs are major players in the global real estate market.

- Private Equity: Investing directly in private companies that are not listed on stock exchanges. This often involves taking significant stakes in businesses with high growth potential, but also higher risk.

- Hedge Funds: Investing in more complex and often aggressive strategies managed by hedge funds, aiming for higher returns but also involving higher fees and risks.

- Infrastructure: Investing in long-term projects like airports, toll roads, power plants, ports, and telecommunications networks. These offer stable, long-term returns and often align with strategic national interests.

- Alternative Investments: This can include anything from timberland and farmland to commodities and even art or collectibles, further diversifying the portfolio.

-

3. Global Reach:

- SWFs invest across continents and emerging markets, not just in developed economies. This global perspective allows them to capitalize on growth opportunities wherever they arise and mitigate risks associated with over-exposure to any single region.

-

4. Patient Capital:

- Their long-term horizon means SWFs can afford to be "patient capital." They can invest in illiquid assets (like private equity or real estate) that take years to mature, and they are less pressured to sell off assets during market downturns. This often allows them to buy assets at lower prices when others are selling.

-

5. Growing Focus on ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance):

- Increasingly, SWFs are integrating ESG factors into their investment decisions. This means considering a company’s environmental impact, its social responsibility (e.g., labor practices, community engagement), and its corporate governance (e.g., board structure, transparency). This shift reflects a growing awareness of sustainability and long-term value creation beyond pure financial returns.

V. Types of Sovereign Wealth Funds

While all SWFs share common characteristics, they can be categorized based on their primary objectives:

- 1. Stabilization Funds: Designed to shield the national budget and economy from commodity price volatility (e.g., oil and gas prices). Funds are deposited during boom times and withdrawn during busts.

- 2. Savings/Future Generation Funds: Aim to convert non-renewable assets into a diversified financial portfolio, ensuring wealth for future generations after natural resources are depleted. The Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global is a prime example.

- 3. Pension Reserve Funds: Created to meet future pension liabilities of the state, often as part of a broader social security system.

- 4. Reserve Investment Funds: Manage official foreign currency reserves that exceed what’s needed for standard central bank operations, aiming for higher returns than traditional reserve management.

- 5. Strategic Development Funds: Invest in specific industries or projects, often domestically, to stimulate economic growth, diversify the economy, or achieve strategic national goals.

VI. Key Characteristics of SWFs

Beyond their types and investment strategies, SWFs possess several distinguishing features:

- State Ownership: They are government-owned and managed, making them distinct from private investment firms.

- Long Investment Horizon: Their focus is on decades, not quarters, allowing for long-term strategic investments.

- Large Capital Base: They typically manage hundreds of billions, sometimes trillions, of dollars.

- Global Diversification: Investments are spread across various asset classes and geographical regions.

- Passive vs. Active Management: Some funds employ mostly passive strategies (e.g., tracking market indices), while others actively seek out specific investments and engage in private equity or direct deals.

- Varying Transparency Levels: Some SWFs are highly transparent about their holdings and governance (like Norway’s), while others operate with considerable discretion.

VII. Notable Examples of Sovereign Wealth Funds

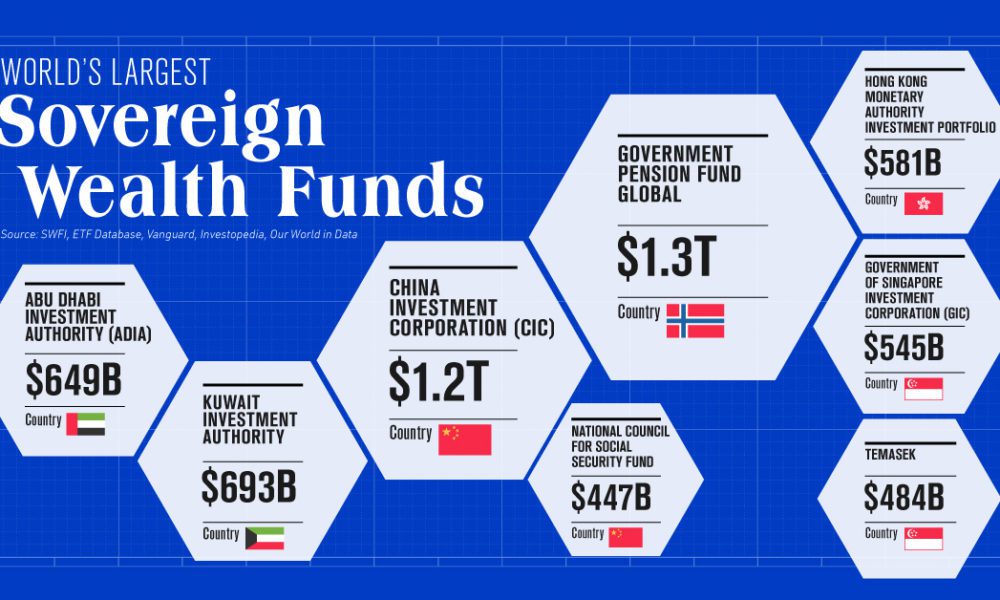

The world’s largest and most influential SWFs hail from diverse corners of the globe:

-

1. Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), Norway:

- Source: Oil and gas revenues.

- Size: Over $1.5 trillion (one of the largest in the world).

- Strategy: Known for its high transparency, ethical guidelines (excluding investments in tobacco, weapons, etc.), and broad diversification primarily into public equities, fixed income, and real estate globally. It’s often cited as the gold standard for SWF governance.

-

2. China Investment Corporation (CIC), China:

- Source: Portion of China’s foreign exchange reserves.

- Size: Over $1.3 trillion.

- Strategy: Manages a diversified global portfolio, including public equities, alternative investments (private equity, hedge funds, real estate), and fixed income. It’s known for its strategic investments aimed at securing resources and technology.

-

3. Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), UAE:

- Source: Oil revenues.

- Size: Estimated over $800 billion.

- Strategy: One of the oldest and most diversified SWFs, investing across virtually every asset class and geography, with a significant allocation to alternative investments and private markets. Known for its very long-term horizon.

-

4. GIC Private Limited (GIC), Singapore:

- Source: Government budget surpluses and foreign reserves.

- Size: Estimated over $700 billion.

- Strategy: Manages Singapore’s foreign reserves, investing in a broad range of assets globally, with a strong emphasis on long-term growth and active management across public and private markets.

-

5. Temasek Holdings, Singapore:

- Source: Initial capital from Singapore’s government, with ongoing returns reinvested.

- Size: Over $400 billion.

- Strategy: Operates more like a commercial investment company, holding and managing a portfolio of state-owned enterprises in Singapore, and making direct investments globally, focusing on long-term value creation.

-

6. Public Investment Fund (PIF), Saudi Arabia:

- Source: Oil revenues, government transfers, and asset sales.

- Size: Over $700 billion.

- Strategy: Central to Saudi Arabia’s "Vision 2030" plan to diversify its economy away from oil. It makes massive, often strategic, investments both domestically (e.g., NEOM megacity) and internationally (e.g., stakes in major tech companies, sports ventures).

VIII. Challenges and Criticisms Facing SWFs

Despite their economic benefits, SWFs are not without their challenges and criticisms:

- 1. Transparency and Governance: A common criticism is the lack of transparency in some SWFs regarding their holdings, investment strategies, and governance structures. This can lead to concerns about accountability and potential political interference.

- 2. Political Influence and Geopolitical Concerns: The sheer size and state ownership of SWFs can raise concerns about their investment motives. Some fear that investments might be driven by political agendas rather than purely economic ones, potentially leading to market distortions or even national security concerns in recipient countries.

- 3. Market Impact and Distortion: The massive capital deployed by SWFs can significantly influence market prices, especially in less liquid asset classes like real estate or private equity, potentially distorting market dynamics.

- 4. Ethical and ESG Dilemmas: While many SWFs are adopting ESG principles, some still face scrutiny over investments in industries with questionable environmental or human rights records, or in regimes with poor governance.

- 5. Managing Public Expectations: In countries where SWFs hold significant wealth, there can be public pressure to spend the funds on immediate social welfare programs rather than saving for the long term, creating a delicate balance for governments.

Conclusion: The Enduring Importance of Sovereign Wealth Funds

Sovereign Wealth Funds are far more than just large pools of money; they are sophisticated instruments of national economic strategy. From ensuring intergenerational equity and stabilizing economies to driving diversification and funding strategic development, their roles are multifaceted and increasingly vital in the global financial landscape.

As the world continues to grapple with economic volatility, climate change, and evolving geopolitical dynamics, SWFs are poised to play an even more significant role. Their long-term investment horizons, patient capital, and growing focus on responsible investing make them powerful forces for shaping the future, not just for their respective nations, but for the global economy as a whole. Understanding these colossal funds is key to comprehending the intricate web of global finance and the pursuit of national prosperity.

Post Comment