What is a Public Good? Characteristics, Challenges & Real-World Examples

Ever wondered why some things, like national defense or the air we breathe, are available to everyone without a direct price tag, while others, like a slice of pizza or a new smartphone, are only yours if you pay for them? This fundamental difference lies at the heart of what economists call a "public good."

Understanding public goods is crucial because they represent areas where traditional markets often fail, leading to the need for government intervention or other collective solutions. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll break down what a public good is, explore its unique characteristics, differentiate it from other types of goods, and discuss the significant challenges in providing them.

What Exactly is a Public Good? A Simple Definition

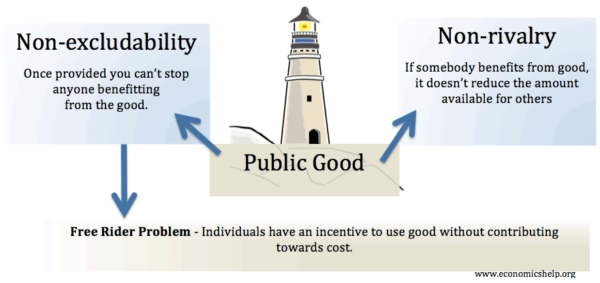

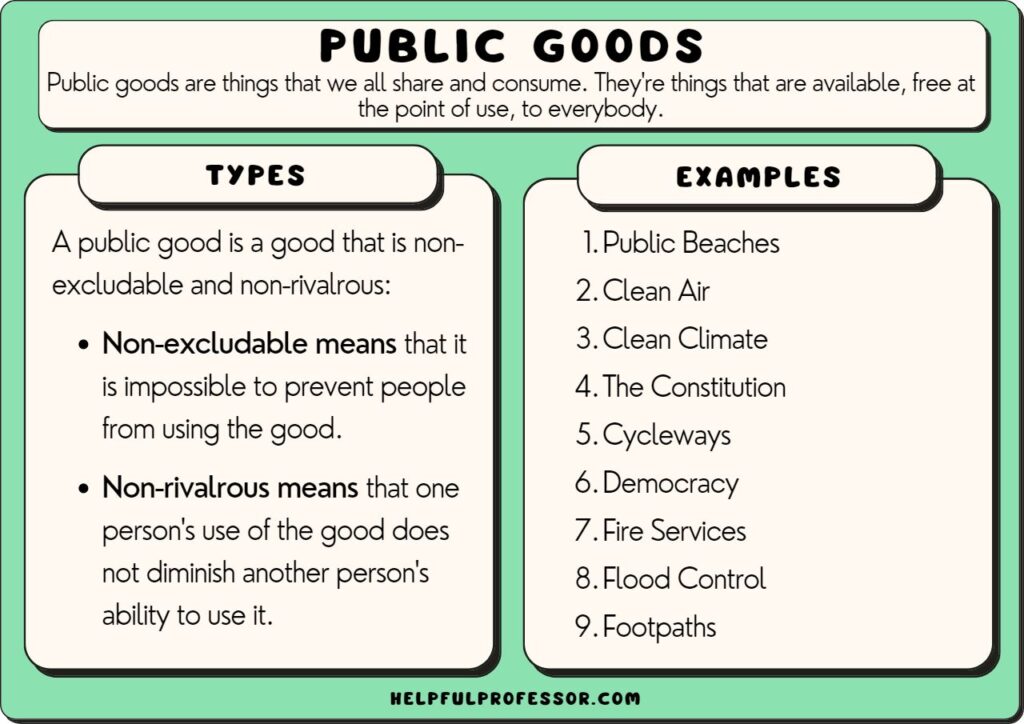

At its core, a public good is something that is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. Don’t worry if those terms sound a bit complex; we’ll break them down.

Imagine a good or service that, once created, is available for everyone to enjoy, and one person’s use doesn’t stop another from using it. That’s the essence of a public good. They are often things that benefit society as a whole, rather than just individuals.

The Two Defining Characteristics of a Public Good

To truly understand public goods, we need to dive into their two core characteristics:

1. Non-Rivalry

What it means: When a good is non-rivalrous, one person’s consumption (or use) of that good does not reduce its availability for others. In simpler terms, multiple people can use or enjoy the good at the same time without diminishing its quality or quantity for anyone else.

Think of it this way:

- A TV Broadcast: If you’re watching a national news broadcast, your viewing doesn’t prevent millions of others from watching it simultaneously. The signal isn’t "used up" by your eyes.

- A Lighthouse: The light from a lighthouse guides one ship safely to shore, but it can guide countless other ships at the same time, without becoming less effective for any of them.

- Clean Air: When you breathe clean air, it doesn’t mean there’s less clean air for someone else to breathe (at least, not until pollution becomes an issue, which is a different problem!).

2. Non-Excludability

What it means: When a good is non-excludable, it is either impossible or extremely costly to prevent people from consuming (or using) it, even if they haven’t paid for it. Once the good exists, it’s virtually impossible to stop anyone from benefiting from it.

Think of it this way:

- National Defense: If a country’s military defends its borders, it protects everyone within those borders, regardless of whether they pay taxes or not. You can’t put a fence around the protection.

- Street Lights: Once a street light is turned on, everyone walking or driving by benefits from the illumination. You can’t charge individual pedestrians for each step they take under its light.

- Basic Scientific Knowledge: Once a new scientific discovery (like the theory of gravity) is made and published, it becomes part of the public domain. You can’t stop people from learning about it or using that knowledge, even if they didn’t fund the original research.

Public Goods vs. Other Types of Goods: A Clearer Picture

To fully grasp what makes a public good unique, it’s helpful to compare it to other categories of goods based on rivalry and excludability. Economists often use a 2×2 matrix to illustrate these distinctions:

| Characteristic | Excludable | Non-Excludable |

|---|---|---|

| Rivalrous | 1. Private Goods | 2. Common-Pool Resources |

| Examples: Pizza, Car, Clothing, Haircut | Examples: Fish in the ocean, Public forest, Clean water in a river | |

| Non-Rivalrous | 3. Club Goods | 4. Public Goods |

| Examples: Cable TV, Private park, Netflix, Gym membership | Examples: National Defense, Street Lights, Basic Research, Lighthouse |

Let’s break down the other three categories:

1. Private Goods (Rivalrous & Excludable)

- Definition: These are the most common goods we encounter daily. One person’s use prevents another’s, and it’s easy to stop people from using them if they don’t pay.

- Examples: A slice of pizza (if I eat it, you can’t), a car (if I drive it, you can’t), a pair of shoes.

2. Common-Pool Resources (Rivalrous & Non-Excludable)

- Definition: These goods are available to everyone (hard to exclude), but one person’s use reduces the amount available for others. This often leads to overuse.

- Examples: Fish in the ocean (if I catch a fish, there’s one less for you), clean water in a shared river (my pollution affects your ability to use it), timber from a public forest. This category is famously associated with the "Tragedy of the Commons."

3. Club Goods (Non-Rivalrous & Excludable)

- Definition: These goods are non-rivalrous (many can use them at once) but are excludable (you can be prevented from using them if you don’t pay). They often involve membership or subscription fees.

- Examples: Cable TV (many can watch, but only if they pay), a private golf course (many can play, but only members), a Netflix subscription (many can stream, but only subscribers).

Why Are Public Goods "Special"? The Market Failure Aspect

Because public goods are non-rivalrous and non-excludable, private businesses often find it difficult to provide them profitably. Why?

- Difficulty in Charging: If you can’t stop people from using it (non-excludable), how do you charge them?

- No Incentive to Produce Enough: If one person’s use doesn’t diminish the good for others (non-rivalrous), the "marginal cost" (cost of one more person using it) is essentially zero. It’s hard to justify charging a price that covers production costs when the good can be enjoyed by everyone for free.

This situation leads to what economists call market failure – a situation where the free market, left to its own devices, fails to produce an optimal or efficient allocation of goods and services. For public goods, the market typically produces too little or none at all.

Key Challenges in Providing Public Goods

Given their unique characteristics, public goods present several significant challenges:

1. The Free-Rider Problem

This is arguably the biggest challenge. The free-rider problem occurs when individuals can benefit from a good or service without contributing to its cost. Since public goods are non-excludable, people can "free ride" on the contributions of others.

- Example: Imagine a neighborhood wants to hire a private security guard. If the guard patrols the streets, everyone benefits from increased safety, even those who didn’t contribute money. Knowing this, some residents might choose not to pay, hoping others will bear the cost. If too many people free-ride, the security guard service might not be funded at all.

2. Under-Provision

As a direct consequence of the free-rider problem, public goods are often under-provided by the private market. If no one wants to pay, or too few people pay, the good simply won’t be produced in sufficient quantities, or sometimes not at all. This means society misses out on beneficial services.

3. Difficulty in Valuation

How do you put a price tag on the benefits of clean air, national security, or a beautiful public park? It’s incredibly hard to determine exactly how much value each individual places on these collective goods, making it difficult to decide how much society should spend on them.

4. Funding Challenges

Since public goods can’t easily be sold in a market, they are typically funded through other means:

- Taxation: Governments usually fund public goods through compulsory taxes collected from citizens. This ensures everyone contributes, mitigating the free-rider problem.

- Voluntary Contributions: For smaller-scale public goods, sometimes voluntary donations or community efforts can fund them, but this is less reliable.

- International Agreements: For global public goods (like climate stability or disease control), international cooperation and funding are necessary.

5. The "Tragedy of the Commons" (Related but Distinct)

While often discussed alongside public goods, the "Tragedy of the Commons" primarily applies to common-pool resources (rivalrous but non-excludable). It describes the depletion of a shared resource by individuals acting independently and rationally according to their own self-interest, despite understanding that depleting the common resource is contrary to the group’s long-term best interests.

- Example: Overfishing in international waters, where no single entity owns the fish, leads to depletion because each fishing boat has an incentive to catch as much as possible before others do.

Who Provides Public Goods?

Given the challenges of market provision, who steps in to ensure we have public goods?

-

Governments: This is the most common and effective provider. Through taxation, governments can overcome the free-rider problem and fund essential public goods like:

- National Defense

- Law Enforcement and Judicial Systems

- Public Roads and Infrastructure (though some can be private)

- Basic Scientific Research

- Environmental Protection

-

Non-Profit Organizations and Charities: For certain public goods, particularly those with a strong social benefit, NGOs and charities play a vital role through donations and volunteer efforts. Examples might include:

- Local park maintenance

- Disaster relief

- Open-source software development

-

International Organizations: For global public goods that transcend national borders, international bodies and agreements are crucial. Examples include:

- Global health initiatives (e.g., WHO efforts to eradicate diseases)

- Climate change agreements

- Peacekeeping missions

Real-World Examples of Public Goods

Let’s look at some classic and contemporary examples to solidify your understanding:

- National Defense: Protects everyone within a nation’s borders, and one person’s protection doesn’t diminish another’s. Impossible to exclude.

- Lighthouses: Guide all ships in the vicinity, non-rivalrous, and impossible to exclude any ship from seeing the light.

- Street Lighting: Benefits all pedestrians and drivers, non-rivalrous, and non-excludable.

- Basic Scientific Research: Once a fundamental discovery is made (e.g., the principles of electricity), it becomes part of the collective knowledge base, benefiting everyone without being "used up."

- Clean Air/Water (to a degree): While pollution can make them rivalrous, the fundamental availability of clean air/water is non-rivalrous and non-excludable.

- Public Parks (without gates/fees): The open space and general aesthetic benefit are non-rivalrous (up to a point of crowding) and non-excludable.

- Flood Control Systems (e.g., dikes, levees): Protect entire communities, non-rivalrous, and non-excludable for residents within the protected area.

Conclusion

Public goods are a fascinating and essential concept in economics. Defined by their non-rivalrous and non-excludable nature, they highlight areas where the free market falls short. The pervasive free-rider problem means that without collective action, often through government intervention funded by taxation, many vital public goods would be under-provided or simply wouldn’t exist.

Understanding public goods helps us appreciate the complex role of government in society and the importance of collective action to provide services that benefit everyone, ensuring a higher quality of life for all.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Is clean air a perfect public good?

A1: Clean air is often cited as an example, but it’s not always "perfect." While the availability of clean air is non-rivalrous and non-excludable, pollution introduces rivalry (my pollution affects your air quality) and can make it harder to access clean air in certain areas. So, while it has strong public good characteristics, it also faces common-pool resource challenges.

Q2: What’s the main difference between a public good and a private good?

A2: The main difference lies in their characteristics:

- Public Goods: Non-rivalrous (many can use at once) and Non-excludable (hard to prevent use).

- Private Goods: Rivalrous (one person’s use prevents another’s) and Excludable (easy to prevent use if not paid for).

Q3: Can a private company provide a public good?

A3: It’s difficult for private companies to profitably provide pure public goods due to the free-rider problem. However, governments can contract private companies to produce public goods (e.g., a private defense contractor building equipment for the military), but the provision (funding and ensuring access) ultimately remains with the government. Sometimes, private firms might provide a "public good" as a side effect of another activity, or if subsidized.

Q4: What is the "free-rider problem" in simple terms?

A4: The free-rider problem means someone benefits from a service or good without paying for it, because they can’t be excluded. They "ride for free" on the contributions of others. This can lead to the good not being provided at all if too many people free-ride.

Q5: Are public parks always public goods?

A5: An open, ungated public park is largely a public good: non-rivalrous (many can enjoy it simultaneously) and non-excludable (anyone can enter). However, if the park becomes extremely crowded, it can become rivalrous (less enjoyment for others), and if it has an entrance fee, it becomes excludable, turning it more into a club good.

Post Comment