What is a "Black Swan" Event in Economics? Unpacking Unpredictable Global Shocks

Imagine a world where everything seems to be following a predictable path. Economies are growing, markets are stable, and experts are confidently forecasting the future. Then, suddenly, something utterly unexpected, something that seemed almost impossible, happens. It hits with devastating force, changing everything in its wake. This, in essence, is what economists and risk managers refer to as a "Black Swan" event.

The term, popularized by scholar and former options trader Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his seminal 2007 book "The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable," describes a specific type of event that has profound, far-reaching consequences, yet is considered virtually impossible to predict.

In an increasingly interconnected and complex world, understanding Black Swan events is crucial for individuals, businesses, and governments alike. While we can’t predict them, recognizing their characteristics can help us build more resilient systems.

What Exactly is a Black Swan Event?

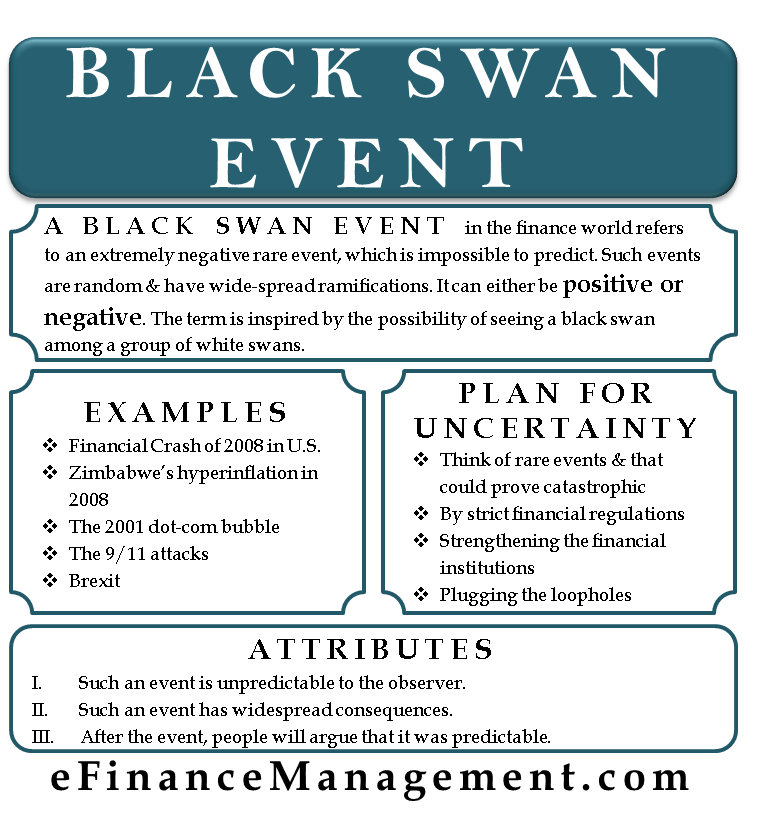

A Black Swan event is not just any major crisis or unexpected turn of events. For an event to truly qualify as a "Black Swan" according to Taleb, it must meet three specific criteria:

- It is an Outlier: The event lies outside the realm of regular expectations. This means that nothing in the past experience or traditional forecasting models would have strongly indicated its possibility. It’s truly rare and unprecedented. Think of it as a statistical anomaly that’s so far off the charts, it barely registers.

- It Carries Extreme Impact: Once it occurs, the Black Swan event has a catastrophic effect. This impact can be economic (market crashes, recessions), social (widespread panic, societal shifts), technological, or geopolitical. It fundamentally alters the landscape and has long-lasting consequences.

- Retrospective Predictability (The "Hindsight Bias"): After the event has happened, people tend to rationalize its occurrence, claiming it should have been predictable. Experts will often construct explanations that make the event seem less random and more logical in hindsight. This "it was obvious all along" phenomenon is a critical component of the Black Swan theory, as it highlights our human tendency to underestimate true randomness and unpredictability.

In short, a Black Swan event is a highly improbable, high-impact surprise that only seems obvious after it has occurred.

The Origin of the "Black Swan" Term

The term itself has a fascinating origin. For centuries, Europeans believed that all swans were white. This belief was based on empirical evidence – every swan ever observed was white. The concept of a "black swan" was used as a metaphor for something impossible or non-existent.

However, in 1697, Dutch explorer Willem de Vlamingh discovered black swans in Western Australia. This single observation shattered a long-held, seemingly irrefutable truth. It demonstrated that what was considered impossible was, in fact, possible, and that our understanding of the world is based on limited observations.

Taleb adopted this metaphor to illustrate how a single, unpredicted event can invalidate a widely accepted theory or assumption, particularly in the realm of economics and finance, where models often rely on past data to predict future outcomes.

Why Do Black Swan Events Matter So Much?

Black Swan events are significant because they expose the fundamental flaws in our traditional approaches to risk management and forecasting.

- Limits of Prediction: Most economic and financial models rely on historical data and statistical probabilities. They are designed to predict "normal" fluctuations and risks that have occurred before. Black Swan events, by definition, fall outside these models, rendering them ineffective.

- Compounding Effects: The impact of a Black Swan event often cascades through interconnected systems. A financial shock can lead to job losses, which can depress consumer spending, further impacting businesses, creating a negative feedback loop.

- Underestimation of Risk: Because these events are considered highly improbable, individuals, businesses, and governments rarely allocate sufficient resources to prepare for them. This lack of preparedness amplifies their destructive power.

- Psychological Impact: The sheer surprise and magnitude of Black Swan events can lead to widespread fear, uncertainty, and a loss of trust in institutions and experts.

Notable Examples of Black Swan Events

While it’s easy to label any major crisis as a Black Swan, it’s important to apply Taleb’s criteria carefully. Here are some commonly cited examples that fit the definition:

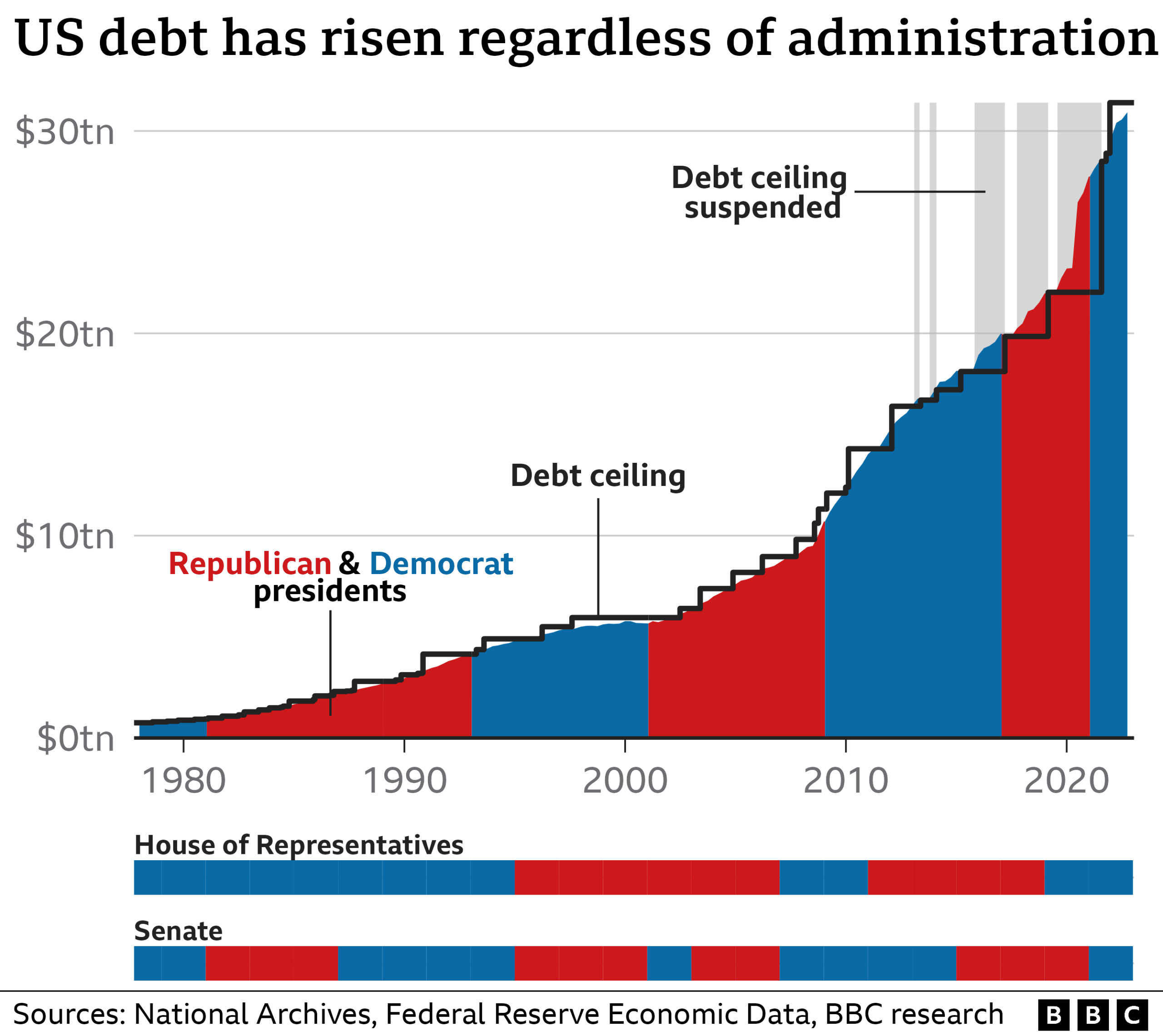

- The Dot-Com Bubble Burst (Early 2000s): The rapid rise of internet-based companies in the late 1990s led to unprecedented valuations, fueled by speculation. Many traditional economic models struggled to explain or predict the scale of this bubble or its subsequent, dramatic collapse, which wiped out trillions in market value and ushered in a recession. In hindsight, the overvaluation became obvious, but few truly predicted the extent of the crash beforehand.

- The September 11th Attacks (2001): While tragic, the 9/11 attacks were an extreme outlier event in terms of their scale, method, and direct targeting of iconic American symbols. No intelligence or risk assessment models had truly predicted such an coordinated, large-scale attack on U.S. soil. The economic and geopolitical impact was immediate and profound, leading to market shutdowns, massive airline industry losses, and a shift in global foreign policy.

- The 2008 Global Financial Crisis: While some economists and investors had warned about subprime mortgages, the scale and speed of the systemic collapse, triggered by the housing market bust and the subsequent failure of major financial institutions like Lehman Brothers, caught most experts and regulators by surprise. The idea that the entire global financial system could teeter on the brink was considered an extreme improbability. Its devastating impact on employment, housing, and global trade was undeniable.

- The COVID-19 Pandemic (2020): While pandemics had been discussed as a theoretical risk, the global scale, rapid spread, and unprecedented economic and social shutdown caused by COVID-19 in 2020 was an extreme outlier. Most economic models did not account for a global, synchronized economic halt. The immediate impact on supply chains, travel, and consumer behavior was immense, and its long-term effects are still unfolding.

Is Every Major Crisis a Black Swan? The Nuance

It’s crucial to understand that not every major crisis or unexpected event qualifies as a Black Swan. For example:

- Predictable Recessions: Economic recessions that follow typical business cycles are not Black Swans, even if their exact timing is uncertain.

- Known Risks: A hurricane hitting a coastal city is not a Black Swan; it’s a known, albeit uncertain, risk that cities prepare for to varying degrees. The unpredictable nature of the event itself is key, not just its impact.

- "Gray Swans": Some events might be considered "gray swans" – highly improbable events that are discussed as possibilities, but their timing or exact manifestation is unknown. For instance, a major cyberattack on critical infrastructure might be a gray swan; we know it’s possible and potentially devastating, but the specifics are uncertain. A true Black Swan, by Taleb’s definition, is something that doesn’t even feature prominently in our risk models or collective consciousness until it happens.

The distinction lies in the element of extreme unforeseeability from a statistical and cognitive perspective.

How Can We Prepare for Black Swan Events?

Since Black Swan events are, by definition, unpredictable, we cannot prepare for them by forecasting their arrival. Instead, the focus shifts from prediction to resilience and robustness.

Here are strategies inspired by the Black Swan theory:

- Build Redundancy and Buffers: Instead of striving for hyper-efficiency, which can make systems fragile, build in extra capacity, diverse supply chains, and financial reserves. For example, a company might have multiple suppliers for critical components, even if it costs a bit more.

- Diversify: For investors, this means not putting all your eggs in one basket. Diversifying investments across different asset classes, industries, and geographies can cushion the blow if one area is severely impacted.

- Scenario Planning, Not Point Forecasting: Instead of trying to predict the single most likely future, businesses and governments should engage in "what-if" scenario planning that includes extreme, low-probability events. This helps develop flexible strategies that can adapt to a wider range of outcomes.

- Embrace Antifragility: Taleb later introduced the concept of "antifragility" – systems that don’t just withstand shocks but actually get stronger from them. This involves learning from mistakes, being open to experimentation, and having decentralized decision-making.

- Focus on Avoiding Single Points of Failure: Identify critical dependencies in systems (economic, technological, social) and work to eliminate or mitigate them.

- Foster Critical Thinking and Skepticism: Be wary of models and experts who claim to predict the future with certainty. Recognize the limits of knowledge and the role of randomness.

Conclusion

Black Swan events are a powerful reminder of the inherent uncertainty in our world, particularly in complex systems like the global economy. They challenge our assumptions about predictability, risk, and control. While they cannot be foreseen, understanding their characteristics allows us to shift our focus from futile attempts at prediction to building more adaptable, resilient, and robust systems.

By embracing diversification, redundancy, and a healthy skepticism towards conventional wisdom, individuals, businesses, and nations can better navigate the inevitable, yet unpredictable, shocks that lie ahead. The goal isn’t to see the Black Swan coming, but to be strong enough to weather its impact when it inevitably arrives.

Post Comment