Unraveling Systemic Risk: Identifying Weaknesses and Safeguarding the Global Financial System

The global financial system is like the circulatory system of the world economy. It facilitates trade, investment, and growth, allowing money to flow where it’s needed. But just as a body’s circulatory system can suffer from blockages or infections, the financial system faces its own unique vulnerabilities. One of the most significant and potentially devastating of these is systemic risk.

For beginners, understanding systemic risk can feel complex, but it’s a crucial concept for anyone interested in economics, finance, or even just the stability of their own financial future. This article will break down what systemic risk is, how we identify its weaknesses, and what measures are taken to protect us from its potentially catastrophic effects.

What Exactly Is Systemic Risk? The "Domino Effect" Explained

Imagine a perfectly aligned row of dominoes. If you tip just one, it triggers a chain reaction, knocking down every other domino in the line. This simple image is perhaps the best way to understand systemic risk in the financial world.

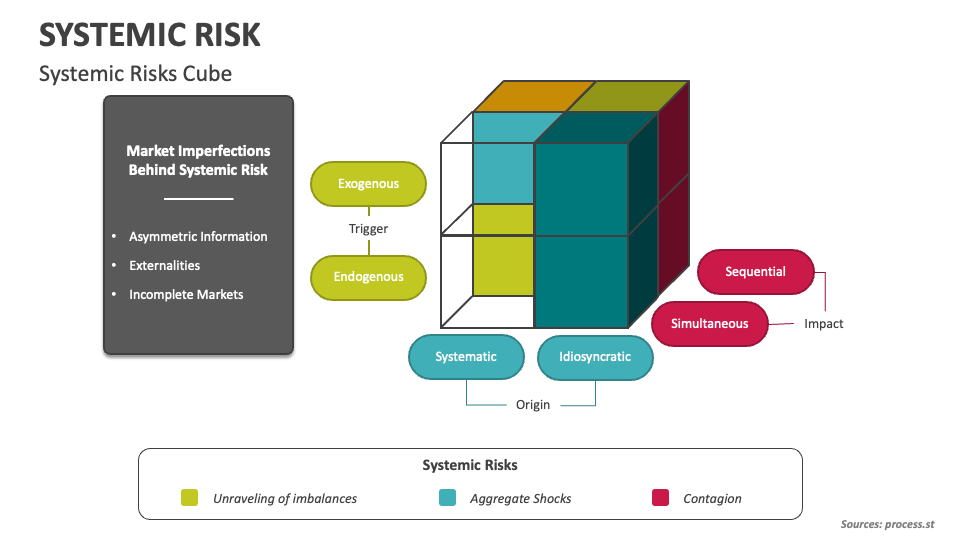

Systemic risk refers to the risk of collapse of an entire financial system or market, as opposed to the collapse of individual firms or components. It’s the danger that problems in one part of the system will spread rapidly and widely, causing a breakdown in the entire system, leading to a severe economic crisis.

Think of it this way:

- Individual Firm Failure: If a small, isolated company goes bankrupt, it’s unfortunate for its employees and investors, but it doesn’t usually threaten the entire economy.

- Systemic Failure: If a major bank, deeply connected to many other financial institutions, collapses, it could drag down other banks, investment funds, and even entire countries through a ripple effect. This is systemic risk in action.

Key Characteristics of Systemic Risk:

- Interconnectedness: Financial institutions (banks, investment funds, insurance companies) are deeply linked through lending, borrowing, and complex financial contracts (like derivatives). A problem in one can quickly spread to others.

- Contagion: This is the "spreading" effect. A shock in one part of the system (e.g., a major bank defaulting) can lead to a loss of confidence, panic, and a rapid withdrawal of funds from other institutions, even healthy ones.

- Cascading Failures: One failure triggers another, creating a chain reaction that can bring down the entire system.

- Loss of Confidence: Fear and uncertainty can cause investors and consumers to pull their money out of banks or markets, further exacerbating the crisis.

Sources of Weakness: Where Does Systemic Risk Originate?

Systemic risk doesn’t just appear out of nowhere. It arises from specific weaknesses and characteristics within the financial system. Identifying these sources is the first step in preventing a crisis.

-

Interconnectedness and Complexity

The modern financial system is incredibly complex. Banks lend to other banks, invest in each other’s securities, and trade intricate financial products (like derivatives) that link them together. If one major player fails, it can create a chain reaction of defaults and losses across the system, much like a spiderweb where pulling one thread affects the whole structure.

-

"Too Big to Fail" (TBTF) Institutions

Some financial institutions are so large and their activities so intertwined with the rest of the economy that their failure would have catastrophic consequences. These are often called "Too Big to Fail" (TBTF).

- The Problem: Because their failure is unthinkable, governments often feel compelled to bail them out using taxpayer money. This creates a "moral hazard," where these institutions might take on more risks, knowing they’ll be rescued if things go wrong.

-

Excessive Leverage

Leverage means borrowing money to make investments. While it can amplify returns, it also amplifies losses. If banks or investors borrow too much and their investments turn sour, their losses can quickly exceed their capital, leading to insolvency. High leverage across the system makes it more fragile and prone to systemic collapse.

-

Asset Bubbles and Bursts

An asset bubble occurs when the price of an asset (like housing or stocks) rises far above its true, underlying value, driven by speculation and irrational exuberance. When the bubble inevitably bursts, prices crash, leading to massive losses for those who invested, and often triggering wider financial distress. The subprime mortgage crisis leading to the 2008 financial crisis is a prime example of a housing bubble bursting.

-

Herding Behavior and Panic

In financial markets, participants sometimes exhibit "herding behavior," where they all follow the same trends or reactions. This can amplify bubbles (everyone buys) or accelerate crashes (everyone sells). If panic sets in, a "bank run" (everyone tries to withdraw their money at once) or a stock market crash can quickly spiral out of control.

-

Regulatory Gaps and Shadow Banking

Financial innovation sometimes moves faster than regulation. Activities that pose risks might occur outside the traditional banking system, in what’s known as shadow banking (e.g., certain hedge funds, money market funds, or peer-to-peer lending platforms). If these unregulated or lightly regulated areas grow large and interconnected, they can become a significant source of systemic risk.

Historical Echoes: When Systemic Risk Became Reality

History offers stark lessons on the devastating impact of systemic risk.

-

The Great Depression (1929)

While not solely a financial crisis, a wave of bank failures in the U.S. in the early 1930s spiraled into a systemic crisis. As one bank failed, public confidence plummeted, leading to "bank runs" where depositors rushed to withdraw their money from other banks, causing even healthy banks to collapse. This destroyed credit, halted investment, and contributed significantly to the worst economic downturn in modern history.

-

The Asian Financial Crisis (1997-1998)

This crisis started with the collapse of the Thai baht and quickly spread across Asia (Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, etc.). It demonstrated currency contagion and the interconnectedness of global capital flows. As foreign investors pulled their money out of one country, it triggered a loss of confidence and capital flight from neighboring economies, causing widespread currency devaluations, bank failures, and economic contractions.

-

The Global Financial Crisis (2008)

Perhaps the most vivid recent example, the 2008 crisis originated in the U.S. subprime mortgage market.

- The Trigger: Loans were given to borrowers with poor credit histories, often with adjustable interest rates that later reset to unaffordable levels.

- The Spreading: These "toxic" mortgages were packaged into complex financial products (Mortgage-Backed Securities – MBS) and sold to banks and investors worldwide.

- The Collapse: When homeowners defaulted en masse, the value of these MBS plummeted, causing massive losses for the banks holding them.

- The Contagion: The failure of Lehman Brothers (a major investment bank) sent shockwaves globally. Banks stopped lending to each other due to distrust, credit markets froze, and the entire system teetered on the brink of collapse, necessitating massive government bailouts.

Identifying Weaknesses: How Do We Spot Trouble Ahead?

Preventing future crises requires vigilance and sophisticated tools to identify emerging weaknesses. Regulators and policymakers constantly monitor the financial system for signs of stress.

-

Stress Testing

Imagine subjecting a car to a simulated crash to see how it holds up. Stress testing does something similar for banks. Regulators simulate severe economic scenarios (e.g., a deep recession, a sharp fall in housing prices, a surge in unemployment) to see if banks have enough capital (financial cushion) to withstand the shocks and continue lending. This helps identify vulnerabilities before a crisis hits.

-

Macroprudential Regulation

Traditionally, financial regulation focused on individual banks ("microprudential"). Macroprudential regulation, however, takes a "big picture" view. It aims to identify and mitigate risks that could threaten the entire financial system. This involves measures like:

- Limiting overall leverage in the system.

- Controlling credit growth to prevent bubbles.

- Requiring more capital from large, interconnected banks.

-

Early Warning Indicators (EWIs)

Economists and regulators monitor various data points that can signal potential trouble. These Early Warning Indicators include:

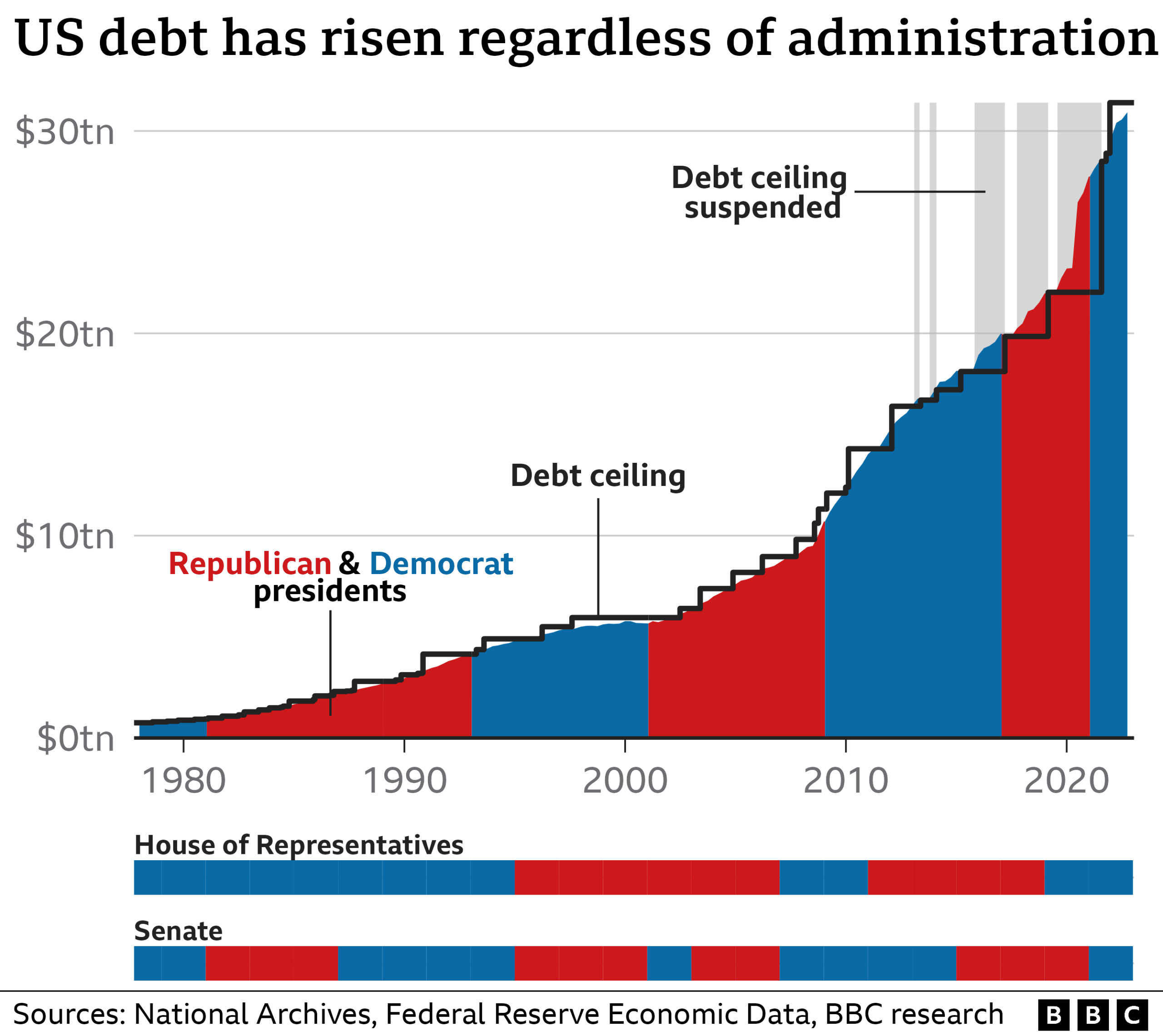

- Rapid growth in credit or debt.

- Sharp increases in asset prices (housing, stocks).

- High levels of interconnectedness between financial institutions.

- Excessive risk-taking by banks.

- Deteriorating global economic conditions.

-

Data Collection and Transparency

A lack of transparency can hide risks. Regulators increasingly demand more detailed data from financial institutions to understand their exposures, interconnections, and potential vulnerabilities. The more data available, the better regulators can assess the true health of the system.

-

Enhanced Supervision and Oversight

Financial supervisors constantly monitor the activities of banks and other financial firms. This includes regular examinations, reviews of risk management practices, and ensuring compliance with regulations. The goal is to catch risky behavior or emerging problems early.

Mitigating Systemic Risk: Strengthening the System

Once weaknesses are identified, measures are put in place to strengthen the financial system and reduce the likelihood and impact of systemic crises.

-

Increased Capital Requirements

Banks are now required to hold significantly more capital (their own money) as a buffer against losses. This means they rely less on borrowed money and have a larger cushion to absorb unexpected shocks without collapsing. This is a core component of the Basel III international banking standards.

-

Improved Liquidity Management

Liquidity refers to how easily an asset can be converted into cash. Banks are now required to hold more high-quality, easily convertible assets (like cash or government bonds) so they can meet their short-term obligations even during times of stress. This helps prevent bank runs.

-

Resolution Regimes for "Too Big to Fail" Institutions

To avoid future bailouts, new frameworks have been developed to allow large, complex financial institutions to fail in an orderly way without destabilizing the entire system. This involves creating "living wills" (plans for orderly bankruptcy) and powers for regulators to wind down failing firms.

-

Enhanced Supervision and Data Sharing

Regulators across different countries and agencies are now better at sharing information and coordinating their efforts. Since financial markets are global, international cooperation is essential to address cross-border systemic risks.

-

Addressing Shadow Banking Risks

Efforts are underway to bring more oversight to the shadow banking sector. This includes monitoring their activities, assessing their risks, and, where appropriate, extending regulation to these previously unregulated areas.

-

Limiting Interconnectedness

While impossible to eliminate, regulators look for ways to reduce excessive interconnectedness, for instance, by encouraging central clearing of complex derivatives contracts, which reduces the direct links between many individual firms.

The Ongoing Challenge

Despite significant progress since the 2008 crisis, the fight against systemic risk is an ongoing challenge. The financial system is constantly evolving, with new technologies, financial products, and business models emerging. This means regulators must remain vigilant, adapting their tools and approaches to identify and mitigate new forms of risk as they arise.

The goal is to build a financial system that is resilient enough to withstand shocks without collapsing, ensuring that the lifeblood of the global economy continues to flow smoothly, even in turbulent times.

Conclusion

Systemic risk is the ultimate nightmare scenario for the financial world: a single point of failure triggering a chain reaction that brings down the entire system. Understanding its origins – from deep interconnectedness and "too big to fail" institutions to asset bubbles and shadow banking – is the first step in safeguarding our economic future.

While the complexities of global finance can be daunting, the principles of identifying weaknesses through stress testing, implementing macroprudential policies, and strengthening institutions through higher capital and liquidity requirements are vital. The lessons of history, particularly the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, underscore the critical importance of continuous vigilance and international cooperation. By diligently working to identify and mitigate these systemic weaknesses, we can strive for a more stable and resilient financial system for everyone.

Post Comment