Unlocking Global Finance: Balance of Payments Explained – Current Account vs. Capital Account

Have you ever wondered how countries manage their money on the global stage? Just like you have a bank account and a budget, every nation tracks its financial interactions with the rest of the world. This comprehensive record is known as the Balance of Payments (BoP).

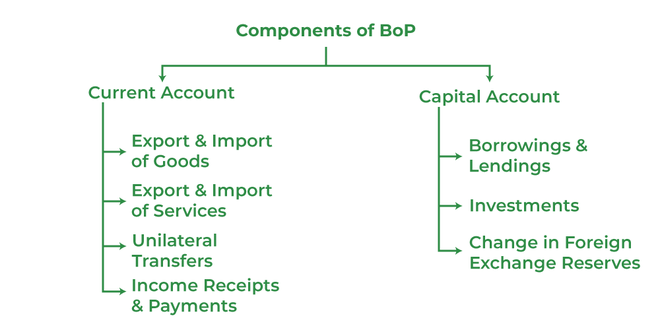

Understanding the Balance of Payments is crucial for anyone looking to grasp global economics, international trade, and even the stability of national currencies. At its heart, the BoP is divided into two major components: the Current Account and the Capital Account (often grouped with the Financial Account). While they sound similar, they track very different types of transactions.

This long-form guide will demystify the Balance of Payments, breaking down the Current Account and Capital Account in an easy-to-understand way, perfect for beginners.

What is the Balance of Payments (BoP)?

Imagine a country’s financial report card. The Balance of Payments is precisely that – a detailed summary of all economic transactions between residents of a country and the rest of the world over a specific period, typically a quarter or a year.

Key Principles of BoP:

- Double-Entry Accounting: Every international transaction is recorded twice – once as a credit and once as a debit. This ensures that, theoretically, the BoP always balances to zero.

- A "Balance" Doesn’t Mean Zero Trade: It doesn’t mean a country isn’t buying or selling anything. It means that for every dollar that leaves the country, a dollar must eventually come back in, either through goods, services, income, or financial assets.

- Snapshot of Global Interactions: It provides insights into a country’s economic health, its trade relationships, investment flows, and its overall financial standing in the world.

Think of it like your personal budget: if you spend more money than you earn, you have to find a way to finance that spending – maybe by selling an asset, borrowing money, or drawing down savings. A country operates similarly on a global scale.

The Current Account: Tracking Day-to-Day Transactions

The Current Account is often considered the most visible part of the Balance of Payments. It records a country’s net income from international transactions, focusing on the flow of goods, services, income, and unilateral transfers. Think of it as tracking a country’s everyday earnings and spending with the rest of the world.

Components of the Current Account:

The Current Account is primarily made up of four sub-accounts:

-

Trade in Goods (Visible Trade):

- This is the largest and most commonly discussed component.

- It records the export and import of physical goods (like cars, electronics, oil, clothing, food).

- Exports (money coming into the country) are recorded as a credit (+).

- Imports (money leaving the country) are recorded as a debit (-).

- The difference between exports and imports of goods is called the Balance of Trade.

-

Trade in Services (Invisible Trade):

- This tracks the export and import of non-physical services.

- Examples include:

- Tourism: When foreign tourists spend money in your country (export of services), or your citizens spend money abroad (import of services).

- Shipping & Transportation: Fees for transporting goods.

- Financial Services: Banking, insurance, and investment advisory fees.

- Consulting & Professional Services: Legal, accounting, and IT services.

- Education: Foreign students paying tuition.

-

Primary Income (Net Factor Income from Abroad):

- This account records income earned by a country’s residents from investments abroad, or income earned by foreigners from investments within the country.

- Income received from abroad:

- Wages earned by citizens working overseas.

- Dividends received from foreign stocks.

- Interest earned on foreign bonds or loans.

- Income paid to foreigners:

- Wages paid to foreign workers in the country.

- Dividends paid to foreign shareholders.

- Interest paid on foreign loans to the country.

-

Secondary Income (Unilateral Transfers):

- This refers to one-way transfers of money or goods between countries, where nothing is received in return. Think of them as "gifts."

- Examples include:

- Remittances: Money sent by migrants working abroad back to their home countries.

- Foreign Aid: Grants or humanitarian assistance.

- Pensions: Payments to retired citizens living abroad.

- Donations: Contributions to international organizations.

Current Account Surplus vs. Deficit

-

Current Account Surplus: This occurs when a country earns more from its exports of goods, services, and income from abroad than it spends on imports and income paid to foreigners.

- What it means: The country is a net lender to the rest of the world. It’s accumulating foreign assets or reducing its foreign liabilities.

- Example: Japan often runs a Current Account surplus, indicating it exports more than it imports and earns significant income from its foreign investments.

-

Current Account Deficit: This occurs when a country spends more on imports and income paid to foreigners than it earns from exports and income from abroad.

- What it means: The country is a net borrower from the rest of the world. It must finance this deficit by attracting foreign investment or by reducing its foreign assets.

- Example: The United States frequently runs a Current Account deficit, meaning it imports more goods and services than it exports.

The Capital Account (and Financial Account): Tracking Long-Term Investments

While the Current Account focuses on income and spending, the Capital Account (often discussed alongside, or even largely subsumed by, the Financial Account in modern economic reporting) tracks changes in a country’s assets and liabilities with the rest of the world. It’s about who owns what across borders.

Historically, this was largely called the "Capital Account." However, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and most modern economists now split it into two distinct parts:

-

The Capital Account (Minor Component):

- This relatively small account records capital transfers that do not involve a change in income.

- Examples include:

- Debt forgiveness: When one country forgives another’s debt.

- Transfers of assets by migrants: When individuals move to a new country and transfer their assets (like property or financial holdings).

- Sales/purchases of non-produced, non-financial assets: Things like patents, copyrights, trademarks, or land sales to embassies.

-

The Financial Account (Major Component):

- This is the much larger and more significant part, dealing with international investment flows. It shows how a country finances its current account balance.

- Components of the Financial Account:

- Direct Investment (Foreign Direct Investment – FDI):

- Involves acquiring a lasting management interest in an enterprise in another country. It’s about setting up or buying businesses.

- Examples: A foreign company building a factory in your country (inflow), or your country’s company buying a business abroad (outflow).

- Portfolio Investment:

- Involves buying financial assets like stocks and bonds purely for financial return, without gaining management control.

- Examples: Foreigners buying your country’s government bonds or company shares (inflow), or your citizens buying foreign stocks (outflow).

- Other Investment:

- Covers a variety of financial transactions, mainly international loans and deposits.

- Examples: Foreign banks lending money to your country’s businesses, or your citizens depositing money in foreign banks.

- Reserve Assets:

- Refers to the foreign currency, gold, and other reserve assets held by the central bank. These are used to manage exchange rates and provide liquidity.

- Examples: The central bank buying foreign currency to strengthen its own currency (outflow of domestic currency), or selling foreign currency (inflow).

- Direct Investment (Foreign Direct Investment – FDI):

Capital/Financial Account Surplus vs. Deficit

-

Capital/Financial Account Surplus: This means a country is experiencing a net inflow of foreign investment. Foreigners are investing more in the country than the country’s residents are investing abroad.

- What it means: The country is attracting capital, often indicating investor confidence.

- Example: If the U.S. attracts significant foreign direct investment and portfolio investment, it will have a Financial Account surplus.

-

Capital/Financial Account Deficit: This means a country is experiencing a net outflow of investment. Its residents are investing more abroad than foreigners are investing in the country.

- What it means: The country’s residents are buying more foreign assets than foreigners are buying domestic assets.

- Example: If China’s companies and citizens invest heavily in foreign countries, it contributes to a Financial Account deficit for China.

The Interplay: How Current Account and Capital Account Balance

Here’s the crucial part: The Current Account and the Capital (and Financial) Account are inextricably linked and must, by definition, balance each other out.

The fundamental identity of the Balance of Payments is:

Current Account (CA) + Capital Account (KA) + Net Errors & Omissions = 0

(In practice, the "Capital Account" here usually refers to the Financial Account, as it’s the dominant component.)

This means:

-

If a country has a Current Account Deficit, it must have a corresponding Capital/Financial Account Surplus.

- In plain English: If a country spends more than it earns on everyday transactions (imports more than it exports, pays more income than it receives), it has to borrow money from abroad or sell off its assets to foreigners to finance that spending. The inflow of foreign investment (Capital/Financial Account surplus) covers the shortfall.

- Example: The U.S. frequently runs a large Current Account deficit. This deficit is largely financed by a significant Financial Account surplus, meaning foreigners are investing heavily in U.S. stocks, bonds, and real estate. They effectively lend money to the U.S. or buy U.S. assets to fund its consumption.

-

If a country has a Current Account Surplus, it must have a corresponding Capital/Financial Account Deficit.

- In plain English: If a country earns more than it spends on everyday transactions (exports more than it imports, receives more income than it pays), it has a surplus of foreign currency. This surplus is then used to invest abroad, essentially lending money to other countries or buying foreign assets. The outflow of domestic investment (Capital/Financial Account deficit) absorbs the surplus.

- Example: Japan often runs a Current Account surplus. This means Japan is accumulating foreign currency, which it then uses to invest in other countries’ assets (e.g., buying U.S. Treasury bonds, investing in foreign companies), leading to a Financial Account deficit for Japan.

The "Net Errors & Omissions" term is included because, in reality, data collection is imperfect. This category acts as an adjustment to ensure the accounts truly balance.

Why Does the Balance of Payments Matter?

Understanding the BoP is not just an academic exercise; it has real-world implications for a country’s economy, its currency, and its people.

-

Economic Health Indicator:

- A persistent Current Account deficit might signal that a country is consuming more than it produces, relying on foreign borrowing to sustain its lifestyle. While not always bad (especially for developing nations attracting investment), a large, growing deficit can be a warning sign of unsustainable consumption or lack of competitiveness.

- A large Current Account surplus might indicate strong export performance and high domestic savings, but could also suggest insufficient domestic demand.

-

Exchange Rates:

- A strong Current Account surplus (meaning more foreign currency is coming in) tends to strengthen a country’s currency.

- A large Current Account deficit (meaning more domestic currency is leaving) can put downward pressure on the currency, making imports more expensive.

-

Government Policy Decisions:

- Policymakers monitor the BoP to make decisions on trade policy (tariffs, quotas), fiscal policy (government spending, taxes), and monetary policy (interest rates).

- For example, a country with a large current account deficit might implement policies to boost exports or attract more foreign investment.

-

Investment Decisions:

- Investors pay close attention to the BoP. A country consistently running large deficits might be seen as a riskier investment, potentially leading to capital flight. Conversely, a stable BoP or a surplus can attract foreign capital.

-

Debt Sustainability:

- If a Current Account deficit is financed primarily through borrowing, it can lead to an accumulation of foreign debt. If this debt becomes too large relative to the country’s economic size, it can become unsustainable, leading to financial crises.

Common Misconceptions About the Balance of Payments

- "A deficit is always bad." Not necessarily. A Current Account deficit can be beneficial for a developing country if it’s financing productive investments (like factories or infrastructure) that will boost future economic growth and export capacity. It becomes problematic when it’s used to finance consumption rather than investment.

- "A balance means no trade." As explained, "balance" refers to the accounting identity, not the volume of trade. Countries trade billions of dollars worth of goods and services, and all those transactions are recorded to balance out.

- "The Balance of Payments is the same as the trade balance." The trade balance (goods exports minus goods imports) is just one part of the Current Account, which in turn is just one part of the overall Balance of Payments.

Conclusion

The Balance of Payments is a critical tool for understanding a country’s economic interactions with the rest of the world. By distinguishing between the Current Account (tracking everyday income and spending on goods, services, and income) and the Capital Account / Financial Account (tracking long-term investment flows and asset ownership), we gain a clearer picture of how a nation finances its global activities.

These two accounts, while distinct, are fundamentally interconnected, always balancing each other out. A Current Account deficit signals a country is borrowing or selling assets to finance its consumption or investment, while a surplus indicates it’s lending or acquiring foreign assets. Grasping this interplay is a cornerstone of international economics, providing vital insights into a nation’s financial health and its role in the global economy.

Post Comment