Understanding Deleveraging: The Painful Yet Essential Process of Debt Reduction

In the complex world of finance and economics, few terms carry as much weight and evoke as much apprehension as "deleveraging." It’s a word that signals a fundamental shift, often following periods of excessive borrowing, and it describes the difficult but necessary journey of reducing debt. Think of it like a financial detox – incredibly uncomfortable in the short term, but vital for long-term health.

This article will demystify deleveraging, explaining what it is, why it happens, why it hurts, and why, ultimately, it’s a crucial step towards a more stable financial future.

What is Deleveraging, Anyway?

At its simplest, deleveraging is the process of reducing the amount of debt an individual, business, or country owes. The term "leverage" refers to the use of borrowed money to finance assets. When you "delever," you’re essentially unwinding that leverage, paying down loans, selling assets to reduce debt, or writing off unpayable debts.

Imagine a person who has accumulated a lot of credit card debt, a car loan, and a mortgage. They are highly "leveraged." If they decide to get their finances in order, pay off their credit cards, sell their expensive car for a cheaper one, and make extra payments on their mortgage, they are engaging in personal deleveraging.

On a larger scale, the concept applies to:

- Households: Reducing personal loans, mortgages, credit card debt.

- Businesses: Paying down corporate bonds, bank loans, or restructuring debt.

- Governments: Reducing national debt through budget cuts or increased taxes.

- Financial Institutions: Banks and investment firms reducing their exposure to risky assets or improving their capital ratios.

Why Does Deleveraging Happen? The Road to Too Much Debt

Deleveraging typically follows a period of excessive credit expansion – a time when borrowing becomes easy, cheap, and widespread. This can happen for several reasons:

- Low Interest Rates: When borrowing is inexpensive, individuals and businesses are encouraged to take on more debt.

- Asset Bubbles: Easy credit often fuels bubbles in asset markets (like housing or stocks). People borrow heavily to buy these assets, expecting prices to rise indefinitely.

- Lax Lending Standards: Banks might become less cautious in who they lend to, leading to a proliferation of risky loans.

- Over-Optimism: During boom times, there’s a collective belief that "things will always get better," leading to overspending and over-investment.

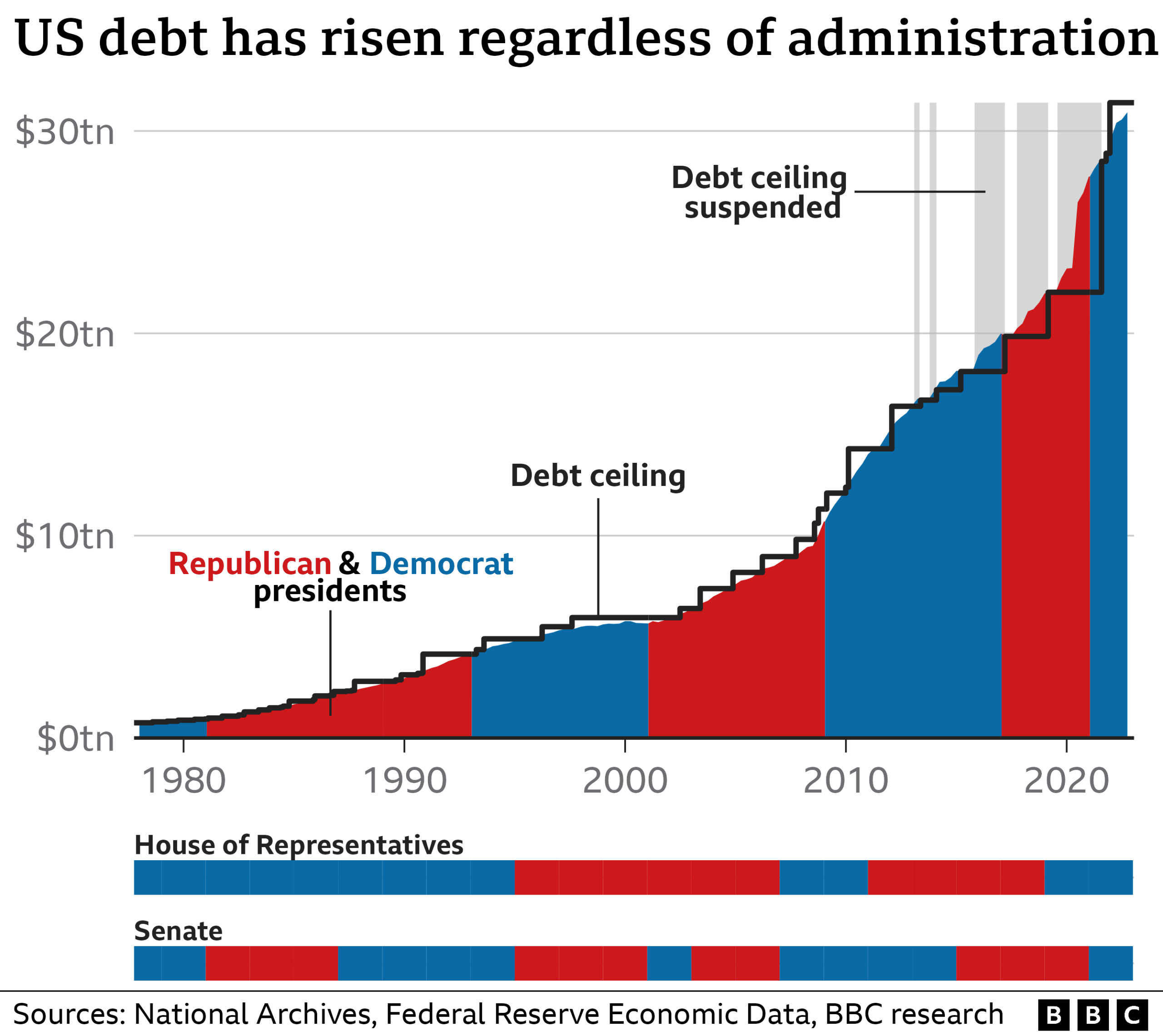

- Government Spending: Governments can accumulate large debts during recessions (stimulus) or wars, or through persistent budget deficits.

Eventually, the party ends. Asset bubbles burst, interest rates rise, or an economic shock (like a recession or a global pandemic) hits. Suddenly, the debt that seemed manageable becomes a crushing burden. People can’t pay their mortgages, businesses face declining sales, and governments see tax revenues fall. This is the point where deleveraging becomes not just an option, but a painful necessity.

The Painful Side of Deleveraging: Why It Hurts

The reason deleveraging is often described as "painful" is because it almost invariably leads to a period of economic slowdown, if not outright recession. Here’s why:

- Reduced Spending:

- Consumers: When households are focused on paying down debt, they have less money to spend on goods and services. This reduces demand for products, hurting businesses.

- Businesses: Companies burdened by debt cut back on investments, expansion plans, and even everyday operations. They might halt new projects, reduce research and development, and delay hiring.

- Governments: To reduce national debt, governments often resort to "austerity measures" – cutting public spending on services like education, healthcare, and infrastructure, or raising taxes.

- Falling Asset Prices: As individuals and businesses sell assets (like homes, stocks, or equipment) to pay down debt, it floods the market, driving down prices. This further erodes wealth and makes it harder for others to borrow against their assets.

- Increased Unemployment: With reduced consumer demand and business investment, companies often respond by laying off workers to cut costs. This leads to higher unemployment rates, further depressing consumer spending.

- Slower Economic Growth (or Recession): The combined effect of reduced spending, falling asset prices, and job losses leads to a significant slowdown in economic activity. In severe cases, it can trigger a deep and prolonged recession.

- Credit Crunch: Banks, also deleveraging, become much more cautious about lending. This "credit crunch" makes it difficult for even healthy businesses and individuals to get loans, stifling economic recovery.

- Social Unrest: Austerity measures and high unemployment can lead to public discontent, protests, and political instability.

Who Deleverages? Different Faces of Debt Reduction

Deleveraging isn’t a monolithic process; it occurs at various levels of the economy, each with its own specific drivers and consequences.

1. Individuals & Households (Personal Deleveraging)

This is perhaps the most relatable form of deleveraging. It happens when families decide to reduce their personal debt load.

- How it Happens:

- Budgeting: Cutting back on discretionary spending (dining out, entertainment, luxury items).

- Increased Savings: Directing more income towards paying down loans rather than consumption.

- Asset Sales: Selling non-essential assets (a second car, a vacation home) to raise cash for debt repayment.

- Defaults: In extreme cases, individuals may default on loans (e.g., foreclosures, bankruptcies), which erases debt but severely damages credit.

- Impact: While financially liberating in the long run, personal deleveraging means less consumer spending in the economy, which can contribute to a broader slowdown.

2. Businesses & Corporations (Corporate Deleveraging)

Companies, like individuals, can accumulate too much debt, especially during boom times when they borrow to expand, acquire other firms, or buy back their own stock.

- How it Happens:

- Cost Cutting: Reducing operational expenses, which often includes layoffs.

- Asset Sales: Selling off non-core business units, property, or equipment to generate cash.

- Reduced Investment: Delaying or canceling plans for new factories, research, or product development.

- Debt Restructuring: Negotiating with lenders for new payment terms or lower interest rates.

- Equity Issuance: Selling new shares to investors to raise cash and pay down debt, but this dilutes existing ownership.

- Impact: Corporate deleveraging can lead to slower innovation, reduced job creation, and a contraction in overall business activity.

3. Governments (Sovereign Deleveraging)

When a nation’s debt becomes too high relative to its ability to repay (its GDP), it may face pressure to deleverage.

- How it Happens:

- Austerity Measures: This is the most common and controversial method, involving:

- Spending Cuts: Reducing budgets for public services (healthcare, education, defense), infrastructure projects, and welfare programs.

- Tax Increases: Raising income tax, sales tax, corporate tax, or introducing new taxes.

- Economic Growth: Ideally, a country can "grow out of its debt" if its economy expands faster than its debt accumulates. However, deleveraging itself often hinders growth in the short term.

- Default/Restructuring: In severe cases, a government might default on its debt or negotiate with creditors to reduce the principal or extend repayment terms (e.g., Greece during the Eurozone crisis).

- Inflation: Governments can sometimes reduce the real value of their debt by allowing inflation to rise. This is a risky strategy as it erodes purchasing power for citizens.

- Austerity Measures: This is the most common and controversial method, involving:

- Impact: Austerity can be socially disruptive, leading to protests and reduced quality of public services. It also slows economic growth.

4. Financial Institutions (Bank Deleveraging)

Banks and other financial firms are at the heart of the credit system. When they have taken on too much risk or their assets decline in value, they need to deleverage.

- How it Happens:

- Selling Off Assets: Banks might sell loans, securities, or other investments to reduce their balance sheets and raise cash.

- Tightening Lending Standards: Becoming much stricter about who they lend to, making it harder for businesses and individuals to get credit.

- Raising Capital: Issuing new shares to investors to increase their equity base, making them less reliant on debt.

- Writing Off Bad Loans: Acknowledging that some loans will not be repaid, which reduces their assets but cleans up their books.

- Impact: Bank deleveraging can lead to a severe "credit crunch," where money stops flowing through the economy, choking off investment and consumption. This was a major feature of the 2008 financial crisis.

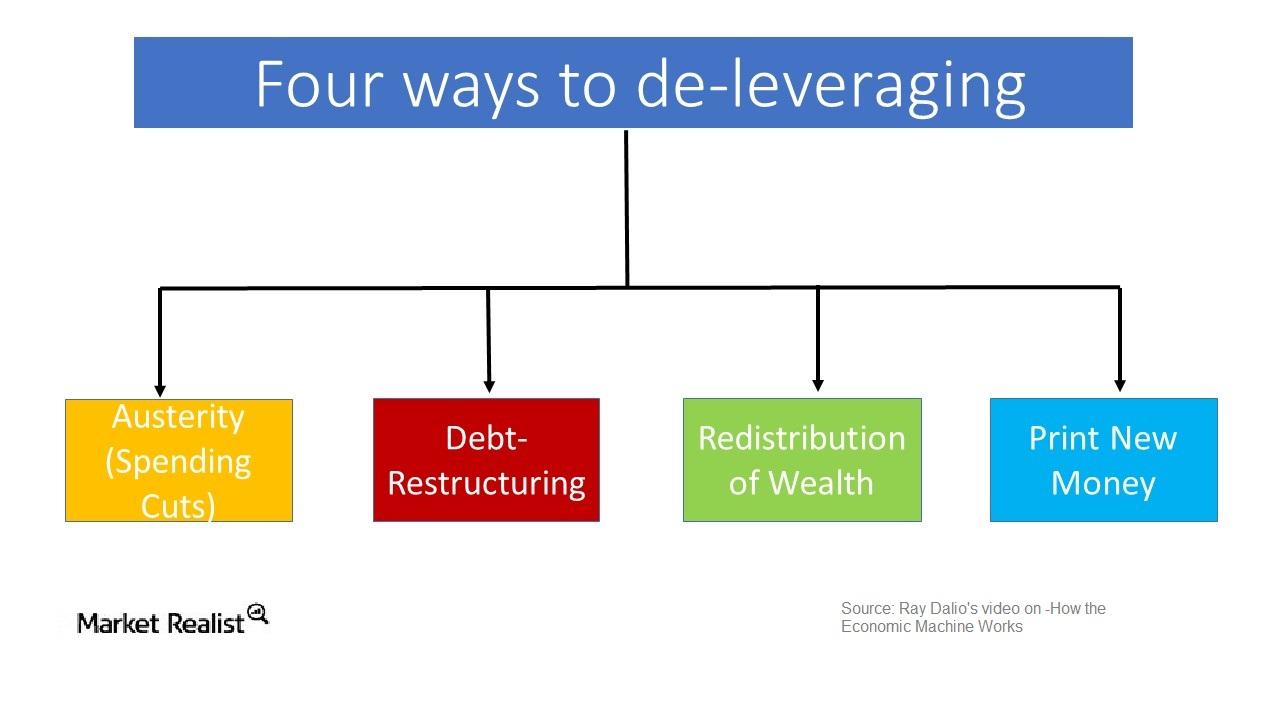

How Does Deleveraging Happen? Mechanisms at Play

Beyond the "who," it’s important to understand the actual mechanisms through which debt is reduced:

- Paying Down Debt (The "Good" Way): This is the ideal scenario, where income exceeds spending, and the surplus is directed towards debt repayment. It’s slow but healthy.

- Defaults and Bankruptcies (The Painful Way): When borrowers cannot pay, debts are written off. This clears the slate for the borrower but creates losses for lenders, potentially leading to a cascade of failures.

- Asset Sales (Selling to Survive): Borrowers sell assets (real estate, equipment, investments) to generate cash to repay debt. This can depress asset prices across the board.

- Austerity (Government’s Tough Choice): As discussed, governments cut spending or raise taxes.

- Inflation (The Sneaky Way): If inflation outpaces interest rates, the real value of debt decreases over time. However, this erodes the value of savings and can be destabilizing.

- Economic Growth (The Best-Case Scenario): If the economy grows robustly, incomes rise, and the debt-to-income ratio naturally improves without painful cuts. However, achieving strong growth during a deleveraging period is challenging.

The Long-Term Benefits: Why the Pain is Worth It

While the short-term pain of deleveraging can be severe, it is often a necessary precursor to long-term financial stability and sustainable growth.

- Financial Stability: Reducing excessive debt makes the entire financial system less vulnerable to shocks. It reduces the risk of widespread defaults, bank failures, and economic crises.

- Sustainable Growth: Once debt levels are at a manageable level, resources that were previously consumed by debt servicing (interest payments) can be redirected towards productive investments, innovation, and genuine economic expansion.

- Increased Resilience: Lower debt means individuals, businesses, and governments have more flexibility to respond to future challenges or opportunities.

- Renewed Confidence: A cleaned-up balance sheet, whether personal or national, can restore confidence among investors, lenders, and consumers, fostering a healthier economic environment.

Think of it as hitting rock bottom and then building a stronger foundation. The old, debt-fueled growth was unsustainable, like a house built on sand. Deleveraging is the process of replacing that sand with solid ground, allowing for more stable and lasting prosperity.

Navigating the Deleveraging Process: Strategies for Resilience

For individuals, businesses, and governments, understanding and preparing for deleveraging can make the process less destructive.

For Individuals:

- Create a Realistic Budget: Track income and expenses to identify areas for saving and debt repayment.

- Prioritize High-Interest Debt: Tackle credit card debt and other high-interest loans first.

- Build an Emergency Fund: Having 3-6 months of living expenses saved can prevent new debt accumulation during tough times.

- Avoid New Debt: Resist the urge to take on new loans unless absolutely necessary.

- Seek Financial Advice: A financial planner can help create a personalized debt reduction strategy.

For Businesses:

- Optimize Cash Flow: Focus on generating strong operational cash flow to repay debt.

- Strategic Asset Sales: Identify non-core assets that can be sold to reduce debt without hindering primary operations.

- Cost Management: Implement strict cost controls and look for efficiencies.

- Diversify Revenue Streams: Reduce reliance on a single product or market segment.

- Communicate with Lenders: Proactively engage with banks and creditors to discuss restructuring options if needed.

For Governments:

- Balanced Approach: Avoid overly aggressive austerity that stifles growth; aim for a mix of spending cuts and targeted investments.

- Structural Reforms: Implement policies that boost productivity, improve education, and foster innovation to support long-term economic growth.

- Transparency: Clearly communicate the reasons for deleveraging and the expected benefits to maintain public trust.

- International Cooperation: For global deleveraging events, coordinated policy responses among nations can mitigate the severity of the downturn.

Conclusion

Deleveraging is more than just an economic term; it’s a profound and often painful transformation that reshapes economies and societies. It’s the moment of reckoning when the consequences of excessive borrowing become unavoidable. While the short-term pain of reduced spending, job losses, and economic slowdown is real, it is a necessary evil.

By understanding deleveraging, we can better prepare for its effects and, more importantly, appreciate its ultimate goal: to build a more resilient, stable, and sustainable financial future, free from the crushing weight of unsustainable debt. It’s the bitter medicine that eventually leads to better health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Deleverage_final-68fb2be54778406cb424fe816ee607bd.png)

Post Comment