The Psychology of Economic Crises: How Fear and Panic Drive Market Crashes

Economic crises are a grim reality of our financial world. From the Great Depression to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the recent economic tremors caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, these periods of hardship bring widespread job losses, business failures, and a general sense of uncertainty. When we talk about economic crises, we often focus on the numbers: GDP figures, unemployment rates, stock market indices. But what if we told you that behind these cold statistics lies a deeply human story?

The truth is, economic crises aren’t just about banks, interest rates, or trade deficits. They are profoundly shaped by human psychology, especially the powerful emotions of fear and panic. In this long-form article, we’ll dive into the fascinating world of behavioral economics to understand how our minds, with all their biases and instincts, can both trigger and intensify economic downturns. We’ll explore why a little fear can be healthy, but how unchecked panic can turn a financial wobble into a full-blown catastrophe.

What Exactly is an Economic Crisis? (Simplified)

Before we delve into the mind, let’s quickly define what an economic crisis is. Imagine the economy as a complex machine. An economic crisis is when that machine suddenly breaks down or slows down dramatically.

Key characteristics often include:

- Recession or Depression: A significant, widespread, and prolonged downturn in economic activity (like people buying less, businesses producing less).

- High Unemployment: Many people losing their jobs.

- Bankruptcies: Businesses failing.

- Falling Asset Prices: The value of stocks, houses, and other investments drops sharply.

- Lack of Confidence: People, businesses, and investors lose trust in the future of the economy.

While a crisis can start with "real" problems (like a housing bubble bursting or a supply chain disruption), the psychological reaction to these problems is what often fuels their severity and spread.

The Human Element: Why Psychology Matters in Economics

For a long time, traditional economics assumed that people are mostly rational actors. This means they make decisions based on logical thinking, always aiming to maximize their own benefit, and processing all available information perfectly. If this were truly the case, economic crises might be more predictable and less severe, as everyone would react calmly and logically.

However, the field of behavioral economics (which combines psychology and economics) has shown us that humans are far from perfectly rational. Our decisions are heavily influenced by:

- Emotions: Fear, greed, hope, anxiety.

- Cognitive Biases: Mental shortcuts that can lead to systematic errors in judgment.

- Social Influences: What others are doing or saying.

In times of economic uncertainty, these psychological factors become magnified, turning what might be a manageable downturn into a spiraling crisis.

Key Psychological Drivers of Fear and Panic in a Crisis

Let’s break down the specific psychological forces that come into play during an economic crisis, driving fear and, ultimately, panic.

1. Loss Aversion: The Pain of Losing

Imagine you find $100 on the street. You feel good, right? Now, imagine you lose $100 from your wallet. Which feeling is stronger? For most people, the pain of losing $100 feels much more intense than the pleasure of gaining $100. This is called loss aversion.

- In a Crisis: When stock markets fall or housing prices drop, people don’t just see numbers on a screen; they feel the very real pain of their wealth diminishing. This feeling is often twice as strong as the joy they felt when their investments were growing. This intense fear of further losses can trigger panic selling, where people rush to sell their assets even at low prices, just to stop the bleeding.

2. Herd Mentality: Following the Crowd

Humans are social creatures. We often look to others for cues on how to behave, especially in uncertain situations. This is known as herd mentality or social proof.

- In a Crisis: If you see everyone around you panicking – pulling money out of banks, selling stocks, or stocking up on goods – your natural instinct might be to do the same, even if you don’t fully understand why. "If everyone else is doing it, it must be the right thing to do, or at least the safe thing to do." This collective behavior can quickly amplify a problem. For example, if a few people withdraw money from a bank due to a rumor, others might fear the bank is failing and rush to withdraw their money too, potentially causing the bank to fail (a bank run).

3. Uncertainty and Ambiguity: The Scariest Unknown

Humans dislike the unknown. We crave certainty and predictability. When the future is unclear, our brains go into overdrive, often imagining the worst-case scenarios.

- In a Crisis: Economic crises are by their nature periods of immense uncertainty. Will I lose my job? Will my investments recover? How long will this last? This lack of clear answers creates a fertile ground for anxiety and fear to fester. When the situation is ambiguous, rumors spread easily, and people tend to interpret information in the most negative light, further fueling their fears.

4. Cognitive Biases: Our Brain’s Shortcuts Go Wrong

Our brains use shortcuts (called heuristics or biases) to make quick decisions. While often helpful, they can lead us astray during a crisis.

- Confirmation Bias: We tend to seek out and interpret information in a way that confirms our existing beliefs. If you’re already fearful, you’ll pay more attention to news stories and opinions that reinforce your fear, ignoring information that might suggest stability.

- Availability Heuristic: We tend to overestimate the likelihood of events that are easily recalled or vivid in our memory. If you constantly hear about people losing their jobs or businesses closing, you might overestimate your own risk, even if the statistics don’t support it.

- Anchoring Bias: We tend to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we receive (the "anchor"). If the market takes an initial sharp drop, that low point can become an anchor, making people believe prices will only go down further, even if fundamentals suggest otherwise.

5. The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: Believing Makes It True

Perhaps one of the most powerful psychological phenomena in economics is the self-fulfilling prophecy. This is where a belief or expectation, simply because it is held, causes the event to happen.

- In a Crisis: If enough people believe the economy is going to crash, they will start acting in ways that make it crash.

- Consumers, fearing job loss, stop spending money. Businesses, seeing reduced demand, lay off workers. This leads to more unemployment, less spending, and the cycle continues.

- Investors, fearing a market crash, sell their stocks. This mass selling drives down prices, fulfilling the initial fear of a crash.

The Contagion of Fear: How Panic Spreads

Fear and panic in an economic crisis aren’t isolated feelings; they are highly contagious. Think of it like a virus that spreads rapidly through a population.

- Media and Social Media: In our interconnected world, news (and rumors) travel at lightning speed. A scary headline or a viral post about a market drop can instantly trigger anxiety in millions. Social media platforms, in particular, can amplify fear through echo chambers and rapid sharing, often without critical verification.

- Word-of-Mouth: Conversations with friends, family, and colleagues play a huge role. Hearing about someone else’s financial struggles or worries can quickly make you feel the same way.

- Financial Interconnectedness: The financial system itself is interconnected. If one major bank is perceived to be in trouble, fear can spread to other banks, as people worry about their money being safe across the entire system. This lack of trust is a critical ingredient for widespread panic.

This contagion can lead to a rapid loss of confidence – confidence in institutions, in the government, and in the future. Once confidence erodes, it’s incredibly difficult to restore, making recovery from a crisis much harder.

Real-World Examples of Fear and Panic in Action

Let’s look at how these psychological principles have played out in history:

- The Great Depression (1929 onwards): A prime example of bank runs driven by panic. As a few banks failed, people feared their own banks would be next. They rushed to withdraw their deposits, leading to many healthy banks collapsing simply because they didn’t have enough cash on hand to meet the sudden demand. This was a classic self-fulfilling prophecy fueled by herd mentality and lack of trust.

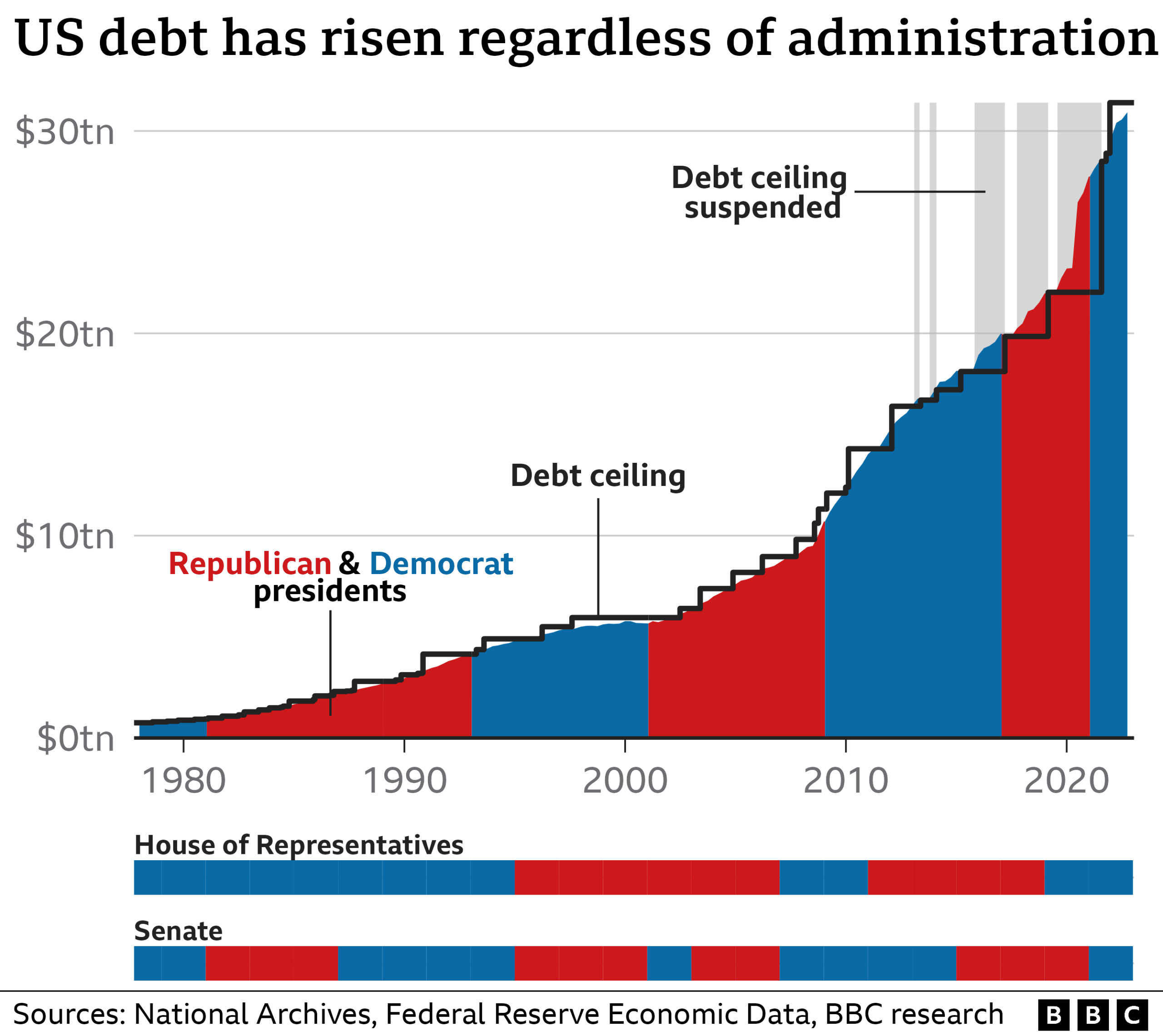

- The 2008 Global Financial Crisis: While rooted in complex financial products (subprime mortgages), the crisis was exacerbated by a massive loss of confidence. When Lehman Brothers collapsed, fear spread rapidly through financial markets. Banks stopped lending to each other because they didn’t trust each other’s solvency, effectively freezing credit markets and sending shockwaves through the global economy. Loss aversion and uncertainty led to widespread panic selling in stock markets.

- COVID-19 Economic Shock (2020): The sudden global lockdown and the immense uncertainty about the virus’s spread and economic impact led to immediate and intense fear. Consumers stopped spending, businesses closed, and stock markets plunged. Panic buying of essentials (like toilet paper) was a clear example of herd mentality and fear of scarcity. The speed of the downturn was heavily influenced by the psychological shock.

Mitigating the Panic: What Can Be Done?

Understanding the psychology of economic crises isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s crucial for both individuals and policymakers to navigate these turbulent times more effectively.

For Individuals: Building Psychological Resilience

- Educate Yourself: Understanding basic economic principles and how markets work can help you differentiate between rational concerns and irrational panic.

- Focus on the Long Term: For investments, remember that markets historically recover. Short-term fluctuations are normal. Avoid making impulsive decisions based on daily news cycles.

- Diversify Your Investments: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. A diversified portfolio can help cushion the blow of downturns in specific sectors.

- Build an Emergency Fund: Having savings set aside for unexpected events (like job loss) can reduce the immediate pressure to panic sell or make desperate decisions.

- Limit News Overload: While staying informed is good, excessive consumption of negative news can heighten anxiety. Take breaks from financial news feeds.

- Recognize Your Biases: Be aware of your own tendency towards loss aversion or herd mentality. When you feel the urge to panic, pause and question if it’s a rational response or an emotional one.

For Governments and Institutions: Restoring Trust and Calming Fears

- Clear and Consistent Communication: Leaders must communicate openly, honestly, and calmly. Conflicting messages or a lack of transparency can quickly erode public trust and fuel panic.

- Swift and Decisive Action: Hesitation or perceived inaction by central banks and governments can exacerbate fears. Bold, clear policies (like bank deposit insurance, stimulus packages, or liquidity injections) can quickly reassure markets and the public.

- Strengthen Safety Nets: Robust social safety nets (unemployment benefits, food assistance) can reduce individual fear and prevent a downward spiral in consumer spending.

- Regulate Information (Responsibly): While free speech is vital, combating harmful misinformation and rumors, especially around financial institutions, is crucial.

- Build Trust in Institutions: Strong, well-regulated financial institutions and clear regulatory frameworks help build confidence that the system is sound and protected.

- Promote Financial Literacy: Educating the public about personal finance and economic cycles can empower individuals to make more informed decisions.

Conclusion: Understanding Our Minds in Times of Crisis

Economic crises are complex beasts, influenced by a myriad of factors. But beneath the layers of financial data and policy debates lies a fundamental truth: human psychology, particularly the interplay of fear and panic, is a powerful, often underestimated, force.

From the pain of loss aversion to the magnetic pull of herd mentality and the dangerous power of self-fulfilling prophecies, our minds play a central role in both triggering and intensifying economic downturns. By understanding these psychological drivers, we can become more resilient investors, more informed citizens, and collectively work towards building a more stable and psychologically aware economic future. The next time you hear about a market dip or an economic slowdown, remember that it’s not just about the numbers; it’s also about the human mind and its profound impact on our shared financial destiny.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is behavioral economics?

A1: Behavioral economics is a field that combines insights from psychology and economics to understand why people sometimes make irrational decisions with their money. It studies how emotions, cognitive biases, and social influences affect economic choices, challenging the traditional view that people are always perfectly rational.

Q2: Can fear alone cause an economic crisis?

A2: While fear alone might not start every crisis, it can certainly turn a minor economic problem into a major one. Fear and panic can create a "self-fulfilling prophecy," where widespread belief in a downturn leads people to act in ways (like mass selling or reduced spending) that actually cause the downturn to worsen.

Q3: How does "loss aversion" affect my investments during a crisis?

A3: Loss aversion makes the pain of losing money feel much stronger than the pleasure of gaining it. During a crisis, this can lead investors to panic sell their assets at low prices, even if it’s not a rational long-term strategy, just to avoid the emotional pain of seeing further losses.

Q4: What is "herd mentality" in the context of economics?

A4: Herd mentality is the tendency for people to follow the actions of a larger group, even if those actions contradict their own beliefs or information. In a crisis, if many people start pulling money out of banks or selling stocks, others might follow suit, fearing they’ll be left behind or lose out, even without a clear reason.

Q5: How can governments use psychology to manage economic crises?

A5: Governments can use psychological insights by communicating clearly and transparently to build trust, taking swift and decisive action to reassure markets, implementing strong safety nets to reduce individual fear, and combating misinformation to prevent panic from spreading. The goal is to restore confidence and prevent irrational behavior.

Post Comment