The Principal-Agent Problem: Aligning Interests in Economics – Your Easy Guide

Have you ever hired someone to do a job for you – perhaps a mechanic to fix your car, a lawyer to handle a case, or even just a babysitter for your kids? If so, you’ve likely encountered a subtle, yet pervasive, challenge known as the Principal-Agent Problem.

It’s a core concept in economics, business, and even politics, dealing with the fundamental difficulty of ensuring that one person (the "agent") acts in the best interests of another (the "principal") when their own interests might not perfectly align. This isn’t just about bad intentions; it’s often a natural consequence of different goals, information gaps, and the simple reality that people are motivated by their own well-being.

Understanding the Principal-Agent Problem is crucial for anyone navigating the complexities of modern life, from running a successful business to making informed decisions as a consumer or a citizen. This long, SEO-friendly guide will break down this vital economic concept into easy-to-understand terms, exploring its causes, manifestations, and, most importantly, the strategies used to align interests and overcome its challenges.

What Exactly is the Principal-Agent Problem?

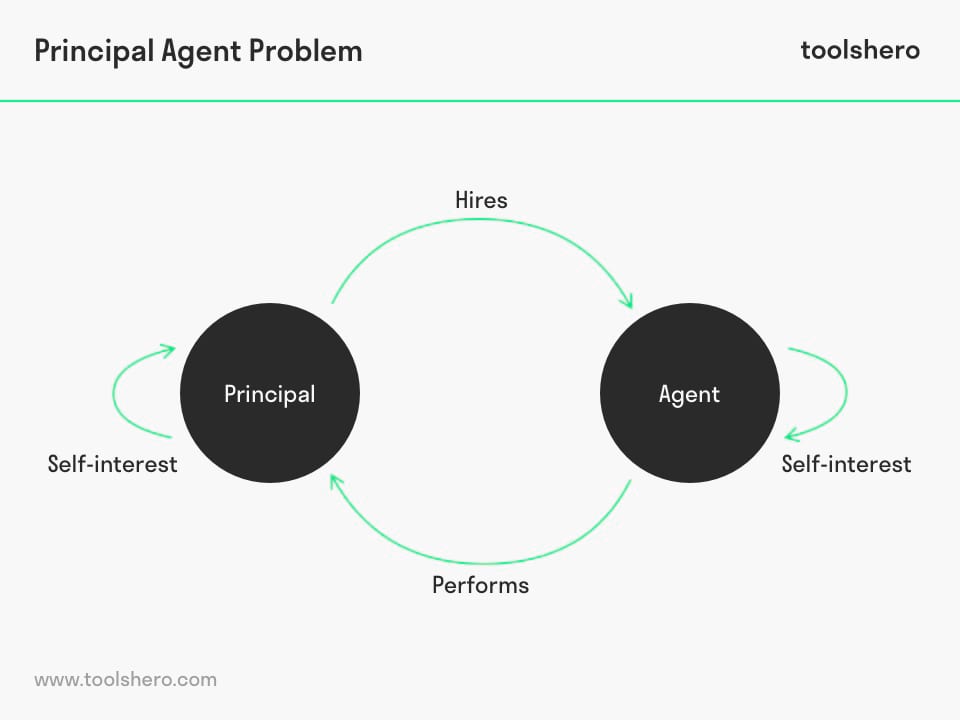

At its heart, the Principal-Agent Problem describes a conflict of interest that arises when one person or entity, the Principal, delegates authority to another person or entity, the Agent, to act on their behalf. The Agent is expected to make decisions and take actions that benefit the Principal.

Here’s a simple breakdown of the roles:

- Principal: The individual or group who delegates authority. They are the ones whose interests need to be served. Think of them as the "employer" or "client."

- Agent: The individual or group who acts on behalf of the Principal. They are the ones performing the task or making the decisions. Think of them as the "employee" or "service provider."

The "problem" arises because the Agent may have different interests, goals, or access to information than the Principal. This can lead the Agent to make decisions that prioritize their own benefit (e.g., more leisure, higher pay, less effort) over the Principal’s optimal outcome (e.g., maximum profit, best service, lowest cost).

In essence, it’s about the challenge of getting someone else to do what you want them to do, especially when you can’t perfectly monitor their actions or when they know more than you do.

Why Does This Problem Arise? The Root Causes

The Principal-Agent Problem isn’t just a random occurrence; it stems from a few fundamental realities of human interaction and economic transactions:

-

Information Asymmetry: This is arguably the most significant cause. Information asymmetry means that one party in a transaction has more or better information than the other.

- The Agent often has more information: They might know more about the effort required for a task, the true condition of a product, or the best way to achieve a goal.

- The Principal often has less information: They can’t perfectly observe the Agent’s effort, expertise, or the real costs involved. This makes it difficult for the Principal to verify if the Agent is truly acting in their best interest.

- Example: When you take your car to a mechanic, they often know far more about what’s wrong and what repairs are truly needed than you do.

-

Conflicting Goals and Interests: Principals and Agents, being distinct individuals or entities, naturally have their own objectives.

- Principal’s Goal: Typically, to maximize their own utility, profit, or achieve a specific outcome at the lowest possible cost.

- Agent’s Goal: Typically, to maximize their own utility, which might include higher wages, less effort, job security, or personal gain, which might not always align perfectly with the Principal’s desired outcome.

- Example: A CEO (agent) might prefer to invest in a low-risk project that guarantees their bonus, even if shareholders (principals) would prefer a higher-risk, higher-reward venture.

-

Difficulty in Monitoring and Measuring Effort/Outcome: It’s often hard for the Principal to directly observe the Agent’s effort, dedication, or the true quality of their work.

- Even if the outcome is visible, it might be influenced by factors beyond the Agent’s control (e.g., market conditions, unforeseen circumstances), making it hard to solely attribute success or failure to the Agent’s effort.

- Example: How do you precisely measure the "effort" of a salesperson? Their sales numbers might be affected by the overall economy, not just their individual drive.

Key Manifestations of the Problem: Moral Hazard and Adverse Selection

The Principal-Agent Problem often manifests in two distinct but related phenomena:

-

Moral Hazard:

- What it is: This occurs after a contract or agreement has been made. It’s the risk that one party (the Agent) will take on more risks or behave differently because they are insulated from the full consequences of their actions, often because the costs or negative outcomes will be borne by the other party (the Principal).

- Think of it as: "Letting your guard down" or "taking advantage once the deal is done."

- Common Scenarios:

- Insurance: Once insured, people might be less careful (e.g., driving recklessly after getting car insurance, or not locking doors after getting home insurance).

- Employees: An employee might shirk responsibilities or put in less effort if their pay is fixed and monitoring is difficult.

- Banks: Banks might take on excessive risks if they know they’ll be bailed out by the government (taxpayers as principals).

- Key Trigger: The Agent’s behavior changes after the agreement, due to a lack of full accountability for their actions.

-

Adverse Selection:

- What it is: This occurs before a contract or agreement is made. It’s a situation where one party in a transaction has information about their own characteristics or quality that the other party lacks, leading to a "bad" or "adverse" selection by the uninformed party.

- Think of it as: "Hidden information leading to a bad choice."

- Common Scenarios:

- Insurance: Individuals who know they are high-risk (e.g., have chronic illnesses) are more likely to seek out comprehensive health insurance, while healthy individuals might opt for less coverage or none. This can lead to insurance pools dominated by high-risk individuals, driving up premiums for everyone.

- Used Car Market: Sellers of used cars know more about the true condition of their vehicle than potential buyers. This can lead to "lemons" (poor quality cars) being disproportionately offered for sale, as good cars are kept or sold elsewhere. Buyers, fearing lemons, might only be willing to pay a lower price, making it unprofitable to sell good cars.

- Job Market: Unproductive workers might try to present themselves as highly productive to get hired.

- Key Trigger: The Agent’s pre-existing characteristics or hidden information influences the Principal’s decision before the transaction.

Real-World Examples of the Principal-Agent Problem

The Principal-Agent Problem isn’t just a theoretical concept; it permeates almost every aspect of our economic and social lives.

- Business:

- Shareholders (Principals) vs. CEO/Management (Agents): Shareholders want to maximize company profits and stock value. CEOs might prioritize personal compensation, empire-building (growing the company size for prestige), or job security over pure profit maximization, especially if their bonuses aren’t directly tied to long-term shareholder value.

- Employer (Principal) vs. Employee (Agent): The employer wants maximum productivity and dedication. The employee might want to minimize effort for their given wage, take longer breaks, or use company resources for personal tasks.

- Healthcare:

- Patient (Principal) vs. Doctor (Agent): Patients rely on doctors for their expertise. Doctors might recommend unnecessary tests or procedures (over-treatment) if they are paid per service, or they might prioritize their own schedule over the patient’s convenience.

- Repairs and Services:

- Car Owner (Principal) vs. Mechanic (Agent): The car owner wants effective, honest repairs at a fair price. The mechanic, having superior knowledge, might recommend unnecessary repairs or overcharge for parts and labor.

- Homeowner (Principal) vs. Contractor (Agent): Similar to the mechanic example, a contractor might use cheaper materials or cut corners if not properly supervised, knowing the homeowner lacks the expertise to detect it.

- Law and Finance:

- Client (Principal) vs. Lawyer (Agent): A client wants the best legal outcome. A lawyer paid by the hour might prolong a case, or a lawyer paid by contingency might push for a quick settlement that benefits them more than the client.

- Investor (Principal) vs. Financial Advisor (Agent): An investor wants their portfolio to grow. An advisor might recommend investments that offer them higher commissions, even if they aren’t the absolute best fit for the client’s risk tolerance or goals.

- Politics:

- Voters (Principals) vs. Politicians (Agents): Voters elect politicians to represent their interests. Politicians, once in office, might prioritize re-election, personal gain, or the interests of special donors over the welfare of their constituents.

Strategies to Align Interests: Solutions to the Principal-Agent Problem

While the Principal-Agent Problem is inherent in many relationships, various strategies can be employed to mitigate its effects and better align the interests of Principals and Agents. These solutions often aim to reduce information asymmetry, create shared incentives, and improve monitoring.

-

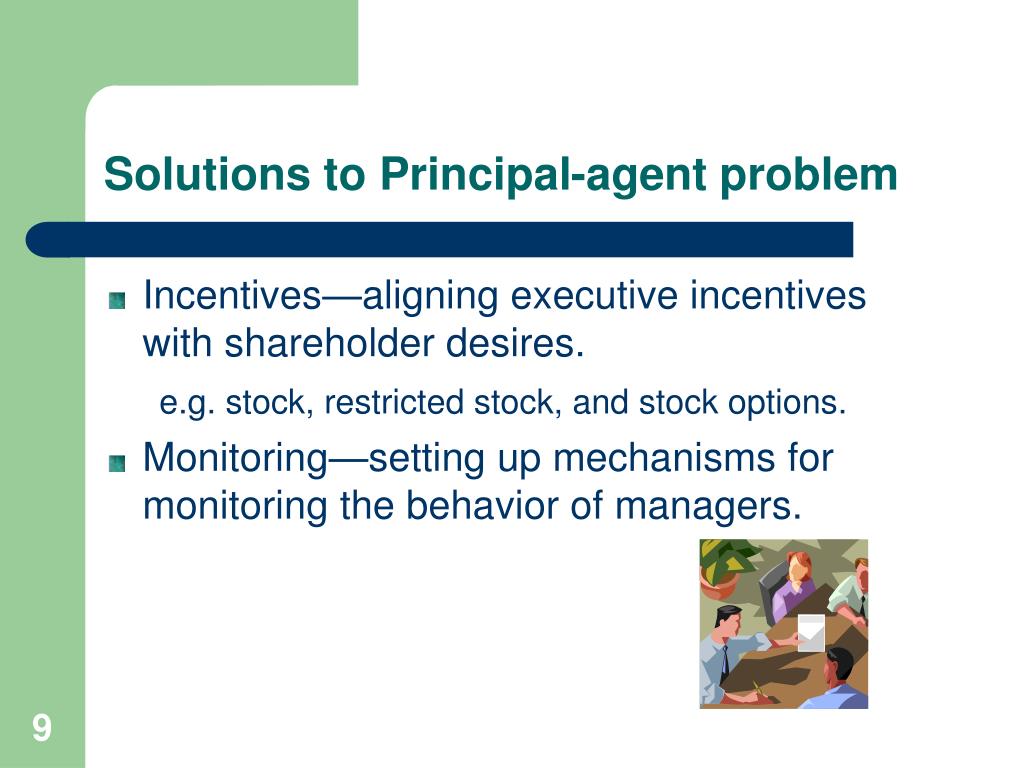

Incentive Systems:

- How it works: Tie the Agent’s rewards directly to the Principal’s desired outcomes. This makes the Agent’s self-interest align with the Principal’s goals.

- Examples:

- Performance Bonuses: Employees get extra pay if they meet specific targets (e.g., sales quotas, project completion on time).

- Stock Options/Shares: Executives or employees receive company stock, making them "owners" and giving them a direct stake in the company’s long-term success.

- Commissions: Salespeople earn a percentage of the sales they generate.

- Profit Sharing: Employees receive a portion of the company’s profits.

- Benefit: Directly motivates the Agent to achieve the Principal’s objectives.

- Challenge: Designing incentives that are fair, measurable, and don’t encourage undesirable behavior (e.g., cutting corners to hit a target).

-

Monitoring and Oversight:

- How it works: Principals actively observe, audit, and review the Agent’s actions and performance.

- Examples:

- Regular Performance Reviews: Managers assess employee output and behavior.

- Audits: Financial statements are reviewed by independent third parties to ensure accuracy.

- Surveillance (e.g., cameras): Used in workplaces to deter theft or ensure compliance.

- Reporting Requirements: Agents must regularly provide detailed reports on their activities.

- Benefit: Reduces information asymmetry by giving the Principal more insight into the Agent’s effort and behavior.

- Challenge: Can be costly, time-consuming, and may foster an environment of distrust if overdone. It’s also hard to monitor every aspect of an Agent’s work.

-

Robust Contracts and Agreements:

- How it works: Clearly define roles, responsibilities, performance metrics, expected behaviors, and consequences for non-compliance in a legally binding document.

- Examples:

- Service Level Agreements (SLAs): Specify the quality and timeliness of service expected from a provider.

- Employment Contracts: Detail job duties, working hours, compensation, and grounds for termination.

- Performance Clauses: Outline specific targets that, if not met, can lead to penalties or contract termination.

- Benefit: Provides clarity, sets expectations, and offers legal recourse if the Agent deviates from agreed-upon terms.

- Challenge: It’s impossible to foresee and include every contingency in a contract. Enforcing contracts can also be expensive and time-consuming.

-

Transparency and Communication:

- How it works: Foster an environment where information flows freely between Principal and Agent, reducing information gaps.

- Examples:

- Open-Book Management: Companies share financial information with employees.

- Regular Meetings and Feedback Sessions: Provide opportunities for dialogue and clarification.

- Clear Reporting Channels: Ensure Agents can communicate challenges or issues to Principals.

- Benefit: Builds trust, allows for early problem detection, and ensures both parties have a clearer understanding of the situation.

- Challenge: Requires a commitment from both sides and can be difficult to implement in large, complex organizations.

-

Reputation and Trust:

- How it works: Agents, particularly in long-term relationships, have an incentive to maintain a good reputation to secure future business or employment. Principals also want to build trust to reduce monitoring costs.

- Examples:

- Online Reviews: Platforms like Yelp, Google Reviews, or professional networking sites allow Principals to rate Agents, influencing future business.

- Professional Certifications: Indicate a certain level of competence and adherence to ethical standards.

- Long-term Relationships: Both parties invest in maintaining a positive, ongoing working relationship.

- Benefit: Creates a self-enforcing mechanism where agents are incentivized to perform well to protect their future prospects. Reduces the need for extensive formal controls.

- Challenge: Building trust takes time, and reputation can be fragile. It’s also less effective in one-off transactions.

-

Shared Vision and Culture:

- How it works: Cultivate a workplace culture or shared understanding where the Agent genuinely identifies with the Principal’s goals and values.

- Examples:

- Strong Corporate Culture: Employees feel a sense of belonging and commitment to the company’s mission.

- Employee Engagement Programs: Foster a sense of ownership and involvement.

- Training and Development: Educate agents on the broader impact of their work.

- Benefit: Aligns interests on a deeper, more intrinsic level, leading to greater motivation and ethical behavior without constant external pressure.

- Challenge: Hard to quantify, takes significant effort to build and maintain, and can be difficult to scale.

The Ongoing Challenge: It’s Not a One-Time Fix

It’s important to remember that the Principal-Agent Problem is rarely "solved" permanently. It’s an inherent tension in many relationships. The strategies mentioned above are tools to mitigate the problem, reduce its severity, and better align interests over time.

Organizations and individuals constantly need to adapt their approaches, refine their contracts, adjust incentive systems, and improve communication to address this persistent challenge. The goal is not to eliminate all conflicts of interest (which is often impossible) but to create systems where the Agent’s pursuit of their own well-being naturally contributes to the Principal’s success.

Conclusion: Navigating a World of Delegated Trust

The Principal-Agent Problem is a foundational concept in economics because it helps us understand the complexities of delegation, trust, and motivation in a world where information is rarely perfect. From the boardroom to the doctor’s office, and even in our daily interactions, recognizing this problem empowers us to:

- Design better systems: Whether in business, government, or non-profits, understanding the problem allows for the creation of more effective incentive structures, monitoring mechanisms, and contractual agreements.

- Make smarter decisions: As consumers, knowing about information asymmetry helps us be more discerning when hiring services or buying complex products.

- Be more effective Principals and Agents: By being aware of potential conflicts, both parties can work proactively to build trust, communicate clearly, and ensure that their shared objectives are met.

In a world increasingly reliant on specialization and delegation, the ability to effectively align the interests of Principals and Agents remains a critical skill for economic efficiency, social harmony, and personal success. By applying the insights from the Principal-Agent Problem, we can build more robust, trustworthy, and productive relationships across all facets of our lives.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Principal-Agent Problem

1. What is the Principal-Agent Problem in simple terms?

It’s the challenge that arises when one person (the "Agent") is hired or entrusted to act on behalf of another person (the "Principal"), but their personal interests or access to information might lead the Agent to make decisions that aren’t perfectly aligned with the Principal’s best interests.

2. What are common examples of the Principal-Agent Problem?

- Employer (Principal) vs. Employee (Agent): Employee might shirk work.

- Shareholders (Principals) vs. CEO (Agent): CEO might prioritize personal gain over shareholder value.

- Patient (Principal) vs. Doctor (Agent): Doctor might recommend unnecessary procedures.

- Car Owner (Principal) vs. Mechanic (Agent): Mechanic might overcharge or suggest unneeded repairs.

3. What is the difference between Moral Hazard and Adverse Selection?

- Moral Hazard: Occurs after a contract is made. The Agent’s behavior changes (e.g., becomes riskier, less effortful) because they are shielded from the full consequences. Think "hidden action."

- Adverse Selection: Occurs before a contract is made. One party has hidden information about themselves or a product, leading the other party to make a "bad" choice (e.g., buying a "lemon" car, or an insurance company getting only high-risk clients). Think "hidden information."

4. How can the Principal-Agent Problem be solved or mitigated?

It’s rarely "solved" completely, but its effects can be reduced through strategies like:

- Incentive Systems: Tying the Agent’s pay to the Principal’s desired outcomes (e.g., bonuses, stock options).

- Monitoring and Oversight: Regularly checking the Agent’s performance and actions.

- Clear Contracts: Defining expectations, roles, and consequences explicitly.

- Transparency: Sharing information openly to reduce knowledge gaps.

- Reputation Mechanisms: Relying on the Agent’s desire to maintain a good name.

5. Why is understanding the Principal-Agent Problem important?

It helps us:

- Design more effective organizations and contracts.

- Make better decisions as consumers and clients.

- Understand conflicts of interest in business, politics, and daily life.

- Build more trusting and productive relationships by anticipating and addressing potential misalignments.

Post Comment