The Law of Supply Explained: A Beginner’s Guide to Market Dynamics and Producer Behavior

Have you ever wondered why the price of your favorite smartphone goes up when a new model is released, or why farmers produce more corn when its price is high? The answers to these questions lie in a fundamental economic principle: The Law of Supply.

Understanding supply is crucial for anyone looking to grasp how markets work, from aspiring entrepreneurs to curious consumers. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll break down the Law of Supply from its basic definition to its complex role in shaping market dynamics, all in easy-to-understand language.

What is "Supply" Anyway? Defining a Core Economic Concept

Before we dive into the "law," let’s clarify what "supply" means in economics.

In simple terms, supply refers to the quantity of a good or service that producers are willing and able to offer for sale at various prices during a specific period.

Think of it from the perspective of a business owner, a farmer, or a service provider. Their goal is generally to make a profit. How much they decide to produce and sell depends on many factors, but price is arguably the most significant.

Here are the key characteristics of supply:

- Producer’s Perspective: Supply is always about what sellers are putting into the market.

- Willingness and Ability: Producers must not only want to sell but also have the capacity (resources, technology, labor) to produce the good or service.

- Specific Period: Supply is measured over a defined time frame (e.g., daily, weekly, annually).

- Various Prices: It’s not just about one price; it’s about the range of quantities offered at different possible prices.

The Core Principle: The Law of Supply

Now, let’s get to the heart of the matter. The Law of Supply describes the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity producers are willing to supply.

The Law of Supply states that, all else being equal (ceteris paribus), as the price of a good or service increases, the quantity supplied by producers will also increase, and vice versa.

In simpler terms:

- Higher Price = More Supplied: If producers can sell their product for a higher price, they have a greater incentive to produce more of it.

- Lower Price = Less Supplied: If the price falls, their incentive decreases, and they will likely produce less.

An Everyday Example: The Baker and the Bread

Imagine a local baker.

- If a loaf of bread sells for $2, the baker might produce 50 loaves a day, as that price offers a modest profit.

- However, if the demand for bread suddenly increases, allowing the baker to sell each loaf for $4, they’ll likely be motivated to produce more. They might hire an extra helper, work longer hours, or invest in a new oven to bake 100 loaves a day, knowing they can earn significantly more profit.

- Conversely, if the price drops to $1 per loaf, the baker might find it’s no longer profitable to bake as much, or perhaps even stop baking that type of bread altogether, shifting resources to more profitable items.

This positive relationship between price and quantity supplied is the fundamental concept behind the Law of Supply.

Why Does the Law of Supply Hold True? Understanding Producer Behavior

The Law of Supply isn’t just an arbitrary rule; it’s rooted in logical producer behavior. Here’s why it generally holds:

-

The Profit Motive:

- The primary goal of most businesses is to maximize profit. A higher selling price, all else being equal, means more revenue per unit sold. This increased revenue makes it more attractive to produce and sell more, as it directly contributes to higher profits.

-

Rising Marginal Costs:

- Producing more units often becomes more expensive per unit. For example, a factory might have to pay overtime to workers, use less efficient machines, or source more expensive raw materials to ramp up production quickly.

- To cover these higher marginal costs (the cost of producing one additional unit), producers need to receive a higher price for their goods. A higher price justifies the increased expense of expanding production.

-

New Entrants to the Market:

- When the price of a good or service rises significantly and stays high, it signals strong profitability. This can attract new businesses (new suppliers) to enter the market, further increasing the overall quantity supplied. For instance, if solar panel prices skyrocket, more companies might decide to start manufacturing them.

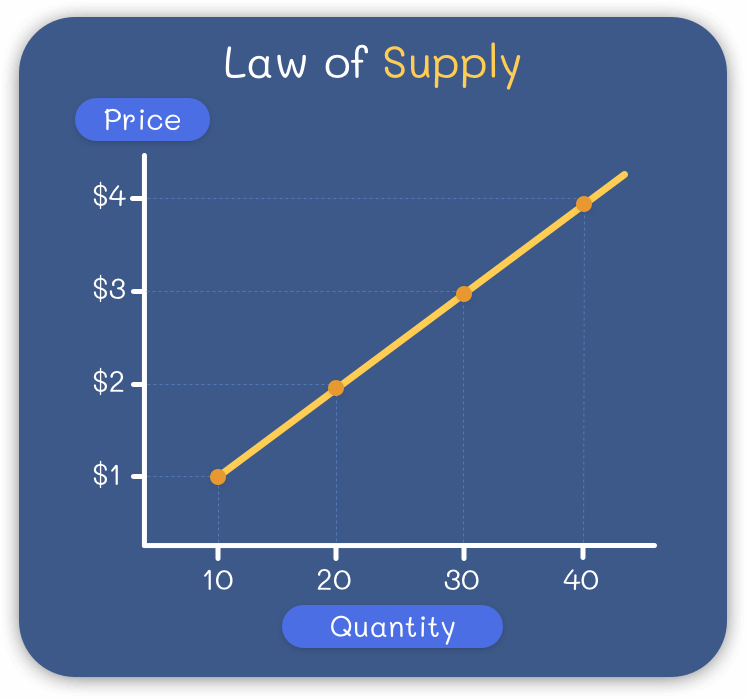

Visualizing Supply: The Supply Curve

Economists use graphs to illustrate the relationship between price and quantity. This graphical representation of the Law of Supply is called the Supply Curve.

- The Supply Schedule: Before we draw the curve, we create a supply schedule, which is a table listing the different quantities of a good that producers are willing and able to supply at various prices.

| Price per Loaf ($) | Quantity Supplied (Loaves per Day) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 10 |

| 2 | 30 |

| 3 | 50 |

| 4 | 70 |

| 5 | 90 |

-

Plotting the Curve: When you plot these points on a graph with price on the vertical (Y) axis and quantity supplied on the horizontal (X) axis, you’ll notice a distinct pattern:

- The Supply Curve slopes upwards from left to right. This upward slope visually represents the positive relationship between price and quantity supplied, as stated by the Law of Supply.

- Every point on the supply curve represents a specific quantity that producers are willing to supply at a given price.

Beyond Price: Determinants of Supply (Shifters of the Supply Curve)

The Law of Supply focuses on how quantity supplied changes due to a change in price, assuming "all else being equal." But what happens when "all else" isn’t equal?

Changes in factors other than the price of the good itself can cause the entire supply curve to shift, indicating a change in overall supply. These are known as the determinants of supply or supply shifters.

When the supply curve shifts:

- Shift to the Right (Increase in Supply): At every given price, producers are now willing and able to supply more of the good.

- Shift to the Left (Decrease in Supply): At every given price, producers are now willing and able to supply less of the good.

Here are the most common determinants of supply:

-

Input Costs (Cost of Resources):

- Definition: The cost of the raw materials, labor, energy, and other inputs used to produce a good.

- Impact:

- Decrease in Input Costs: Makes production cheaper, increasing profitability at any given price. Supply increases (shifts right). (e.g., if the price of flour drops, bakers can produce more bread at the same profit margin).

- Increase in Input Costs: Makes production more expensive, reducing profitability. Supply decreases (shifts left). (e.g., if oil prices soar, transportation costs for all goods increase, reducing supply).

-

Technology:

- Definition: Advances in production methods, machinery, or processes.

- Impact:

- Improved Technology: Makes production more efficient, reduces costs, and allows more output with the same inputs. Supply increases (shifts right). (e.g., automated assembly lines allow car manufacturers to produce more cars faster and cheaper).

- Outdated/Breakdown of Technology: Can hinder production. Supply decreases (shifts left).

-

Government Policies:

- Definition: Taxes, subsidies, and regulations imposed by the government.

- Impact:

- Subsidies: Financial aid or support from the government. Subsidies decrease production costs, increasing supply (shifts right). (e.g., government grants to solar panel manufacturers).

- Taxes: Increase the cost of production. Taxes decrease supply (shifts left). (e.g., an excise tax on cigarettes).

- Regulations: Rules concerning production, safety, or environmental standards. Stricter regulations can increase costs and decrease supply (shifts left); looser regulations can have the opposite effect.

-

Number of Sellers (or Producers):

- Definition: The total count of businesses or individuals producing a particular good or service.

- Impact:

- Increase in Number of Sellers: More producers mean more total output available in the market. Supply increases (shifts right). (e.g., if more restaurants open in a town).

- Decrease in Number of Sellers: Fewer producers mean less total output. Supply decreases (shifts left). (e.g., if many small businesses close down).

-

Expectations of Future Prices:

- Definition: What producers believe the price of their good will be in the future.

- Impact:

- Expectation of Higher Future Prices: Producers might hold back some of their current supply to sell it later at a higher profit. Current supply decreases (shifts left). (e.g., a farmer storing crops if they expect prices to rise after a bad harvest season).

- Expectation of Lower Future Prices: Producers might try to sell off their current stock quickly to avoid future losses. Current supply increases (shifts right). (e.g., a retailer having a sale before new models arrive).

-

Prices of Related Goods (in Production):

- Definition: This refers to goods that can be produced using similar resources or processes.

- Impact:

- Substitute Goods in Production: If the price of a substitute good (something else a producer could make) increases, producers might shift resources to that more profitable good. Supply of the original good decreases (shifts left). (e.g., if the price of corn goes up, a farmer might plant more corn and less soybeans, decreasing the supply of soybeans).

- Joint Products: Goods that are produced together. If the price of one joint product increases, producers will make more of both. Supply of the other joint product increases (shifts right). (e.g., when crude oil is refined, gasoline and diesel are produced. If gasoline prices rise, more crude oil is refined, increasing the supply of both gasoline and diesel).

Crucial Distinction: Movement Along vs. Shift of the Supply Curve

It’s vital to differentiate between these two concepts:

- Change in Quantity Supplied: This is a movement along the existing supply curve. It’s caused only by a change in the price of the good itself. If the price of bread goes from $3 to $4, the quantity supplied moves from 50 to 70 loaves, but the supply curve itself doesn’t move.

- Change in Supply: This is a shift of the entire supply curve (either left or right). It’s caused by a change in one of the determinants of supply (non-price factors). If new technology allows the baker to produce more bread at every price, the entire supply curve shifts to the right.

Supply in Action: Its Role in Market Dynamics

The Law of Supply is not an isolated concept; it works in conjunction with the Law of Demand (which describes consumer behavior) to determine market equilibrium.

- Equilibrium Price and Quantity: Where the supply curve and the demand curve intersect, we find the equilibrium price and quantity – the point where the quantity consumers want to buy exactly matches the quantity producers want to sell.

- Response to Shocks: When a determinant of supply changes (e.g., a new technology emerges), the supply curve shifts. This shift, combined with the demand curve, will lead to a new equilibrium price and quantity in the market. For instance, if supply increases, prices tend to fall, and quantity traded increases.

Understanding the Law of Supply provides insight into:

- Pricing Strategies: How businesses decide what to charge.

- Production Decisions: Why companies increase or decrease output.

- Market Fluctuations: Why prices and availability of goods change over time.

- Government Policy Impact: How taxes, subsidies, and regulations influence industries.

Conclusion: The Cornerstone of Market Understanding

The Law of Supply is a cornerstone of economic understanding, explaining how producers react to changes in prices and other market conditions. By grasping that producers are motivated by profit and respond to higher prices by increasing output, you unlock a fundamental insight into how goods and services flow through our economy.

From the local baker to multinational corporations, the principles of supply dictate production decisions and play a crucial role in determining the prices we pay and the availability of everything we consume. Whether you’re a student, an aspiring business owner, or simply a curious individual, a solid grasp of the Law of Supply is an invaluable tool for navigating the complexities of the economic world.

Post Comment