The Law of Diminishing Returns: Why Output Slowly Grinds to a Halt (A Beginner’s Guide)

Have you ever found yourself adding more and more effort to something, only to see smaller and smaller improvements? Maybe you studied for an extra hour but learned very little new, or you added more ingredients to a dish hoping it would taste better, but it just got muddled. If so, you’ve experienced the Law of Diminishing Returns in action!

It’s a fundamental concept in economics and production, but it applies to almost every area of life. Understanding it can help you make smarter decisions, whether you’re running a business, managing a project, or even just trying to be more productive in your daily life.

In this long, SEO-friendly guide, we’ll break down the Law of Diminishing Returns in simple terms, explore why it happens, look at real-world examples, and discuss how you can navigate its effects.

What Exactly is the Law of Diminishing Returns?

Let’s start with a straightforward definition.

The Law of Diminishing Returns states that if you keep increasing one input (like labor, fertilizer, or advertising budget) while keeping all other inputs fixed, the additional output you get from each extra unit of that input will eventually start to decrease.

Think of it like this:

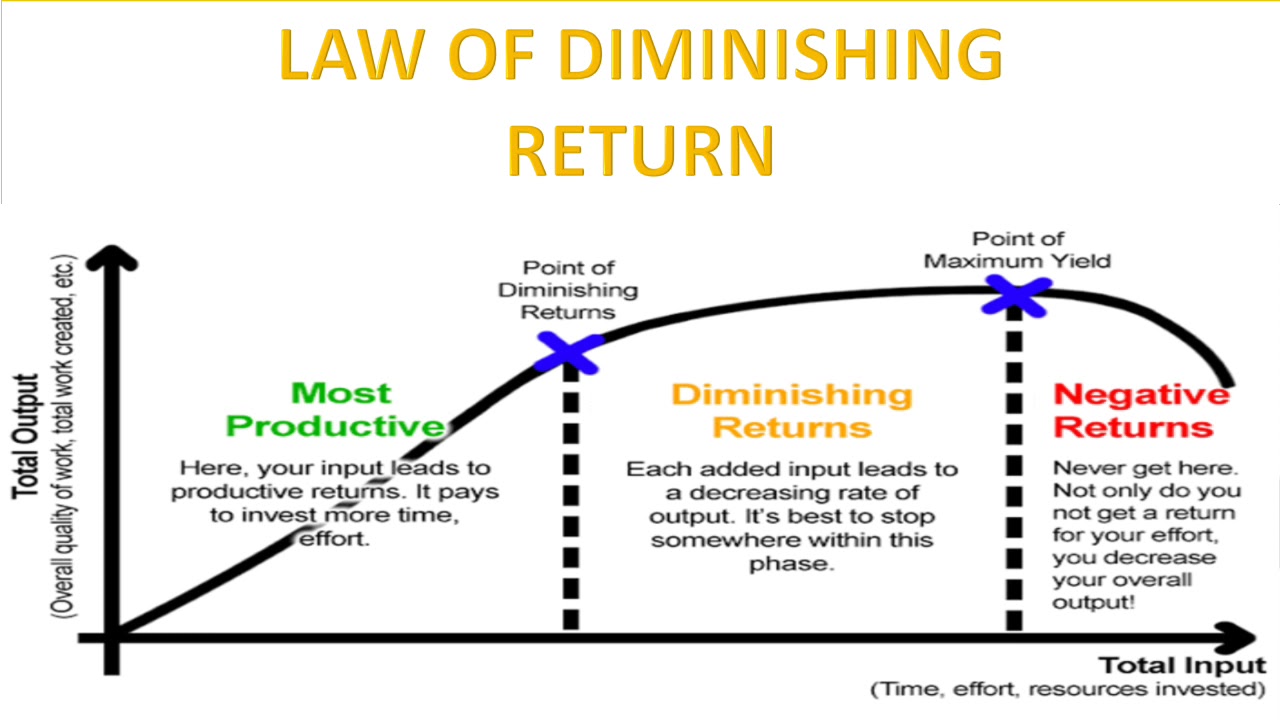

- You start strong: Adding the first few units of input often leads to significant increases in output.

- You hit a sweet spot: There’s usually an optimal point where adding more input still yields good results.

- Then, things slow down: Beyond that point, each additional unit of input still increases total output, but by a smaller and smaller amount.

- Eventually, it might even go backward: In extreme cases, adding too much of that input can actually decrease total output!

The Crucial Condition: Fixed Inputs

The key to understanding diminishing returns is the idea of fixed inputs. This law only applies when at least one input in your production process is fixed or limited. If you could increase all inputs proportionally (e.g., double your land, workers, and tools all at once), you might experience constant returns to scale, but that’s a different concept.

The Classic Example: Farming and Field Workers

To truly grasp the concept, let’s use the most famous example: farming.

Imagine you own a small farm with a fixed amount of land (let’s say, 1 acre). Your goal is to grow as many vegetables as possible. You start hiring farmworkers.

-

Scenario 1: 1 Worker

- Input: 1 worker

- Output: The worker can plant, weed, and harvest efficiently. They produce 100 bushels of vegetables.

- Marginal Product (additional output): 100 bushels

-

Scenario 2: 2 Workers

- Input: 2 workers

- Output: The two workers can divide tasks, helping each other, and use the land more effectively. They produce 180 bushels of vegetables.

- Marginal Product: 80 bushels (180 – 100 = 80)

- Observation: The second worker added a lot of output, but less than the first. Why? Maybe the first worker was already doing the easy stuff, or they started getting in each other’s way just a little bit.

-

Scenario 3: 3 Workers

- Input: 3 workers

- Output: Three workers might still increase total output, but the limited land starts to become a bottleneck. They might have to wait for tools, or accidentally step on plants. They produce 240 bushels.

- Marginal Product: 60 bushels (240 – 180 = 60)

- Observation: The third worker added even less than the second. The "diminishing returns" are clearly setting in.

-

Scenario 4: 4 Workers

- Input: 4 workers

- Output: Now, it’s getting crowded. There’s only so much land. Workers might be idle, or even damage each other’s work. They produce 280 bushels.

- Marginal Product: 40 bushels (280 – 240 = 40)

- Observation: The output is still increasing, but by a much smaller amount.

-

Scenario 5: 5 Workers

- Input: 5 workers

- Output: It’s a mess! Too many people on too little land. They’re tripping over each other, arguing over tools, and accidentally pulling up good plants instead of weeds. They produce 270 bushels.

- Marginal Product: -10 bushels (270 – 280 = -10)

- Observation: Here, we’ve gone beyond diminishing returns into negative returns, where adding more input actually decreases total output. This is an extreme but possible outcome.

The Takeaway from the Farm:

The farm example clearly shows that while adding more workers initially boosts output, there comes a point where the fixed resource (the land) limits how much more benefit each additional worker can bring. The additional output (marginal product) from each new worker starts to shrink.

Why Does Output Start to Slow Down? The Mechanics Behind Diminishing Returns

The reasons behind diminishing returns are logical and often relate to bottlenecks or inefficiencies created by fixed resources.

-

Limited Fixed Resources Become Bottlenecks:

- This is the most common reason. In our farm example, the land was the fixed resource. No matter how many workers you add, they can only work on that 1 acre. If you only have one shovel, five workers can’t all use it at once.

- Example: In a small kitchen, adding more chefs beyond a certain point won’t make food faster; they’ll just bump into each other.

-

Overcrowding and Congestion:

- When too many variable inputs are crammed into a fixed space or process, efficiency drops. Communication becomes harder, movement is restricted, and time is wasted.

- Example: Adding too many cars to a fixed-size highway causes traffic jams, making travel slower, not faster.

-

Lack of Complementary Resources:

- Sometimes, adding more of one input doesn’t help if you don’t also add the right kind of other inputs.

- Example: Hiring 10 more software developers won’t make a project finish faster if you only have one computer server or if the project manager can only oversee a few people effectively. The server or the manager becomes the limiting factor.

-

Specialization Limits:

- Initially, adding more workers allows for specialization (one person plants, another weeds). This boosts efficiency. But once all necessary tasks are specialized, adding more workers means they either do redundant work or just stand around.

- Example: In a small factory, once you have someone for every station on the assembly line, adding another worker doesn’t speed up the line; they just watch.

-

Coordination and Management Challenges:

- The more people or resources you add, the harder it becomes to manage and coordinate them effectively. Meetings take longer, miscommunications increase, and decision-making slows down.

- Example: A small startup with 5 people is agile. A company with 500 people has many layers of bureaucracy, which can slow down innovation.

Beyond the Farm: Real-World Examples of Diminishing Returns

The Law of Diminishing Returns isn’t just for textbooks; it’s everywhere!

-

Studying for an Exam:

- Variable Input: Hours of study

- Fixed Input: Your brain’s capacity, the amount of material to learn, your physical endurance.

- The Effect: The first few hours of studying yield huge gains in understanding. After many hours, you get tired, your focus wanes, and each additional hour brings less new knowledge or retention. Eventually, studying more might just lead to burnout.

-

Advertising Campaigns:

- Variable Input: Advertising budget

- Fixed Input: Market size, customer attention span, uniqueness of your product.

- The Effect: Initially, spending more on ads reaches new customers and boosts sales significantly. But eventually, you’ve reached most of your potential market, or people are tired of seeing your ads. Each extra dollar spent brings fewer new customers or sales, as the "easy" customers have already been acquired.

-

Adding Servers to a Website:

- Variable Input: Number of servers

- Fixed Input: Network bandwidth, database speed, complexity of the code.

- The Effect: Adding the first few servers dramatically improves website speed and handles more users. But if your database is slow or your internet connection is limited, adding more servers won’t help much; they’ll just sit idle, waiting for the bottleneck to clear.

-

Applying Fertilizer to Crops:

- Variable Input: Amount of fertilizer

- Fixed Input: Land size, sunlight, water, soil quality.

- The Effect: A small amount of fertilizer significantly boosts crop yield. More fertilizer adds more, but eventually, the soil can only absorb so much, or the plants can only grow so big, regardless of how much more fertilizer you add. Too much can even burn the plants and decrease yield.

-

Working Out at the Gym:

- Variable Input: Hours spent exercising

- Fixed Input: Your body’s ability to recover, muscle growth rate.

- The Effect: The first few workouts yield noticeable strength and fitness gains. Training for 2-3 hours a day might bring good results. But training for 6-8 hours a day could lead to overtraining, injury, and diminished or even negative progress because your body doesn’t have time to recover and rebuild.

Is Diminishing Returns Always a Bad Thing?

Absolutely not! The Law of Diminishing Returns is not a sign of failure; it’s a natural law that governs most production processes. Understanding it is a powerful tool for making better decisions.

Here’s why it’s important and not inherently "bad":

- It Helps Identify Optimal Points: By understanding diminishing returns, you can figure out the "sweet spot" – the point where adding more input still gives you good returns, but before it becomes inefficient or wasteful.

- It Guides Resource Allocation: It tells you when to stop pouring more of one resource into a fixed system and instead look for ways to increase your fixed resources or optimize other parts of the process.

- It Prevents Waste: Without this understanding, you might endlessly add resources to a problem, thinking "more is always better," leading to massive waste of time, money, and effort.

- It Encourages Innovation: When you hit diminishing returns, it forces you to think creatively about how to overcome the fixed constraints – perhaps by investing in new technology, processes, or expanding your fixed resources.

How to Navigate the Law of Diminishing Returns

Since we can’t escape this law, the best approach is to understand it and use that knowledge to our advantage.

-

Identify Your Fixed Inputs/Bottlenecks:

- What resources in your process are limited? Is it space, equipment, raw materials, management capacity, or even time? Pinpointing these is the first step.

- Example: If your software project is slowing down, is it the number of coders (variable) or the outdated testing infrastructure (fixed)?

-

Monitor Your Marginal Output:

- Keep track of the additional output you get from each additional unit of input. When this starts to noticeably decrease, you’re entering the zone of diminishing returns.

- Example: If adding a fifth salesperson only brings in 10% more sales than the fourth, while the fourth brought in 30% more than the third, you’re seeing diminishing returns.

-

Optimize Resource Allocation:

- Once you hit diminishing returns with one input, consider shifting resources. Instead of adding more of the same input, can you improve the quality of that input, or invest in other areas?

- Example: Instead of hiring a 10th worker for a small coffee shop, perhaps invest in a faster espresso machine or better training for existing staff.

-

Invest in Fixed Resources:

- The most direct way to push back the point of diminishing returns is to increase your fixed inputs.

- Example: If land is your fixed input, buy more land. If factory space is limited, expand the factory. If management capacity is the issue, hire more managers or improve management training.

-

Innovate and Adopt New Technology:

- Technology often helps overcome fixed resource limitations. Automation, new software, or more efficient machinery can drastically increase output without needing to linearly increase variable inputs.

- Example: A robot in a factory can do the work of several human laborers, effectively making the "labor" input more productive without increasing the number of human workers.

-

Diversify or Change the Process:

- Sometimes, the best solution is to completely rethink your approach or diversify your activities.

- Example: If your current advertising channel is showing diminishing returns, explore new marketing channels or develop new products to reach different customer segments.

Key Takeaways About Diminishing Returns

- It’s Universal: Applies to almost all production processes, businesses, and even personal endeavors.

- It Requires Fixed Inputs: This law only occurs when at least one resource is limited or constrained.

- Output Still Increases (Initially): Diminishing returns means the rate of increase slows down, not that total output necessarily drops (unless you reach negative returns).

- It’s a Guide, Not a Problem: Understanding it helps you find optimal points and make efficient resource allocation decisions.

- It Drives Innovation: It encourages businesses and individuals to find new ways to be more productive and overcome limitations.

Conclusion

The Law of Diminishing Returns might sound like a complex economic theory, but at its heart, it’s a simple, intuitive concept: you can’t just keep piling on more of the same thing and expect endlessly better results. There are always limits.

By recognizing when you’re approaching these limits – whether in a business, a project, or even your personal productivity – you can pivot, innovate, and make smarter choices about how you allocate your valuable resources. Embrace this law, and use it to your advantage to achieve greater efficiency and success!

Post Comment