The Gold Standard and Historical Economic Crises: A Beginner’s Guide to Money, Stability, and Collapse

Imagine a world where the value of every dollar, pound, or franc you held was directly tied to a shiny, heavy metal: gold. This wasn’t a fantasy; it was the reality for much of history, under a system known as the Gold Standard. For centuries, it was seen as the bedrock of financial stability, a guarantee against runaway inflation and a facilitator of global trade. Yet, as history unfolded, this very "standard" was implicated in some of the most severe economic crises the world has ever known.

In this long, SEO-friendly article, we’ll dive deep into what the Gold Standard was, how it worked, and critically, its complex and often turbulent relationship with historical economic crises. We’ll break down complex concepts into easy-to-understand language, perfect for anyone looking to grasp this fascinating aspect of economic history.

What Was the Gold Standard? (The Basics Explained)

At its heart, the Gold Standard was a monetary system where a country’s currency had a value directly linked to a specific amount of gold. Think of it like a promise: the government or central bank guaranteed that you could exchange your paper money for a fixed quantity of gold.

Here’s how it generally worked:

- Fixed Price for Gold: A country would set a specific price for gold. For example, the U.S. dollar might be defined as equal to 1/20th of an ounce of gold. This meant an ounce of gold was worth $20.

- Convertibility: Banks were obligated to exchange paper money for gold, and vice versa, at this fixed rate. If you had $20, you could theoretically walk into a bank and get an ounce of gold.

- Gold Reserves: To maintain this promise, countries needed to hold significant reserves of physical gold in their vaults. The amount of paper money they could print was limited by the amount of gold they possessed.

- Fixed Exchange Rates: Because each currency was pegged to gold, currencies automatically had fixed exchange rates against each other. If $20 bought an ounce of gold, and 4 British Pounds also bought an ounce of gold, then $20 was always worth 4 Pounds.

Why was it adopted?

The main appeal of the Gold Standard was its perceived stability and trust. People believed that linking money to a tangible, scarce resource like gold would prevent governments from printing too much money (leading to inflation) and would ensure predictable prices and international trade. It was seen as a discipline on government spending.

The "Golden Age" (and Its Hidden Flaws)

The period before World War I (roughly 1870-1914) is often referred to as the "classical Gold Standard era." During this time, many major economies, including the UK, USA, Germany, and France, were on the Gold Standard.

Perceived Benefits of this Era:

- Price Stability: Proponents argue it led to long-term price stability, as the money supply couldn’t expand rapidly.

- Facilitated International Trade: Fixed exchange rates reduced currency risk for businesses, making cross-border trade and investment easier and more predictable.

- Disciplined Governments: Governments couldn’t easily print money to fund wars or excessive spending, theoretically promoting fiscal responsibility.

However, beneath this veneer of stability, the Gold Standard harbored significant flaws that would contribute to future crises:

- Inflexibility: The biggest problem. If an economy faced a downturn, the government or central bank couldn’t easily increase the money supply or lower interest rates to stimulate growth. They were constrained by their gold reserves.

- Deflationary Bias: If the economy grew faster than the supply of new gold, prices would tend to fall (deflation). While falling prices might sound good, widespread deflation can cripple an economy by making debts harder to repay and discouraging spending and investment.

- "Gold Shocks": Discoveries of new gold (like in California or Alaska) could cause inflation, while a lack of new gold could cause deflation. The monetary system was at the mercy of geological luck.

- Vulnerability to Speculation: Large movements of gold between countries could cause financial instability.

World War I: The First Major Break

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 delivered the first significant blow to the classical Gold Standard. Financing a global war required enormous sums of money, far more than governments could raise through taxes or borrowing alone.

How the War Broke the Gold Standard:

- Printing Money for War: To pay for soldiers, weapons, and supplies, governments needed to print vast amounts of paper money.

- Suspension of Convertibility: To prevent their gold reserves from being depleted (as people would rush to exchange their rapidly devaluing paper money for gold), countries quickly suspended the convertibility of their currencies into gold.

- Massive Inflation: With the link to gold broken and money supply exploding, many countries experienced severe inflation during and after the war.

After the war, there was a strong desire to return to the stability of the Gold Standard. However, the economic landscape had changed drastically, and the attempts to re-establish it in the 1920s proved fragile and ultimately contributed to the coming global catastrophe.

The Great Depression: A Gold Standard Catastrophe?

The Great Depression (starting in 1929) was the most severe economic downturn in modern history, and many economists argue that the Gold Standard played a significant role in both causing and prolonging it.

How the Gold Standard Worsened the Great Depression:

- Deflationary Spiral: As economic activity slowed and banks failed, people hoarded money. Under the Gold Standard, central banks couldn’t easily print more money to counteract this. The money supply contracted sharply, leading to severe deflation (falling prices).

- Impact of Deflation: As prices fell, the real value of debts increased, making it harder for individuals and businesses to pay back loans. This led to more bankruptcies, more unemployment, and a vicious cycle.

- No Room for Monetary Stimulus: In a crisis, modern central banks typically lower interest rates and inject money into the economy to encourage borrowing and spending. Under the Gold Standard, central banks were constrained by their gold reserves. If they lowered rates too much or printed too much money, gold would flow out of the country as people sought more stable currencies.

- Spread of the Crisis: The fixed exchange rates of the Gold Standard meant that economic problems in one country could easily spread to others. If a country faced a gold outflow, it was forced to raise interest rates to attract gold back, which choked off its own economy and further deepened the global recession.

- "Liquidationist" Policy: Some governments and central bankers believed that the economy needed to "liquidate" bad debts and inefficient businesses, arguing that the Gold Standard forced this necessary, painful adjustment. This mindset prevented active intervention to alleviate suffering.

The Escape Route: Abandoning Gold

A crucial piece of evidence supporting the Gold Standard’s role in the Depression is the timing of recovery. Countries that abandoned the Gold Standard earlier (like the UK in 1931 and the USA in 1933) were generally able to recover faster.

- Flexibility Gained: Once off gold, these countries could devalue their currencies (making their exports cheaper), lower interest rates, and increase the money supply, providing much-needed stimulus to their economies.

Bretton Woods: A Modified Gold Standard (1944-1971)

After the devastation of World War II, world leaders were determined to create a more stable international monetary system. In 1944, they met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, and established a new framework that was a hybrid of a Gold Standard and a flexible system.

Key Features of Bretton Woods:

- U.S. Dollar as Anchor: The U.S. dollar was pegged to gold at a fixed rate ($35 per ounce of gold).

- Other Currencies Pegged to the Dollar: Other major currencies (like the British Pound, French Franc, German Mark, Japanese Yen) were pegged to the U.S. dollar at fixed but adjustable rates.

- International Institutions: The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank were created to oversee the system, provide loans, and help countries manage their exchange rates.

Benefits of Bretton Woods:

- Promoted Stability: It provided a degree of exchange rate stability, facilitating the post-war reconstruction and a boom in global trade.

- Reduced Currency Wars: It aimed to prevent competitive devaluations (where countries deliberately weaken their currency to boost exports) that had plagued the interwar period.

The Flaws that Led to its Demise:

- "Triffin Dilemma": This was the core problem. For the system to work, the U.S. had to supply dollars to the world (often through trade deficits) so other countries could hold them as reserves. However, the more dollars held abroad, the less confidence there was in the U.S. ability to convert all those dollars into gold, threatening the system’s credibility.

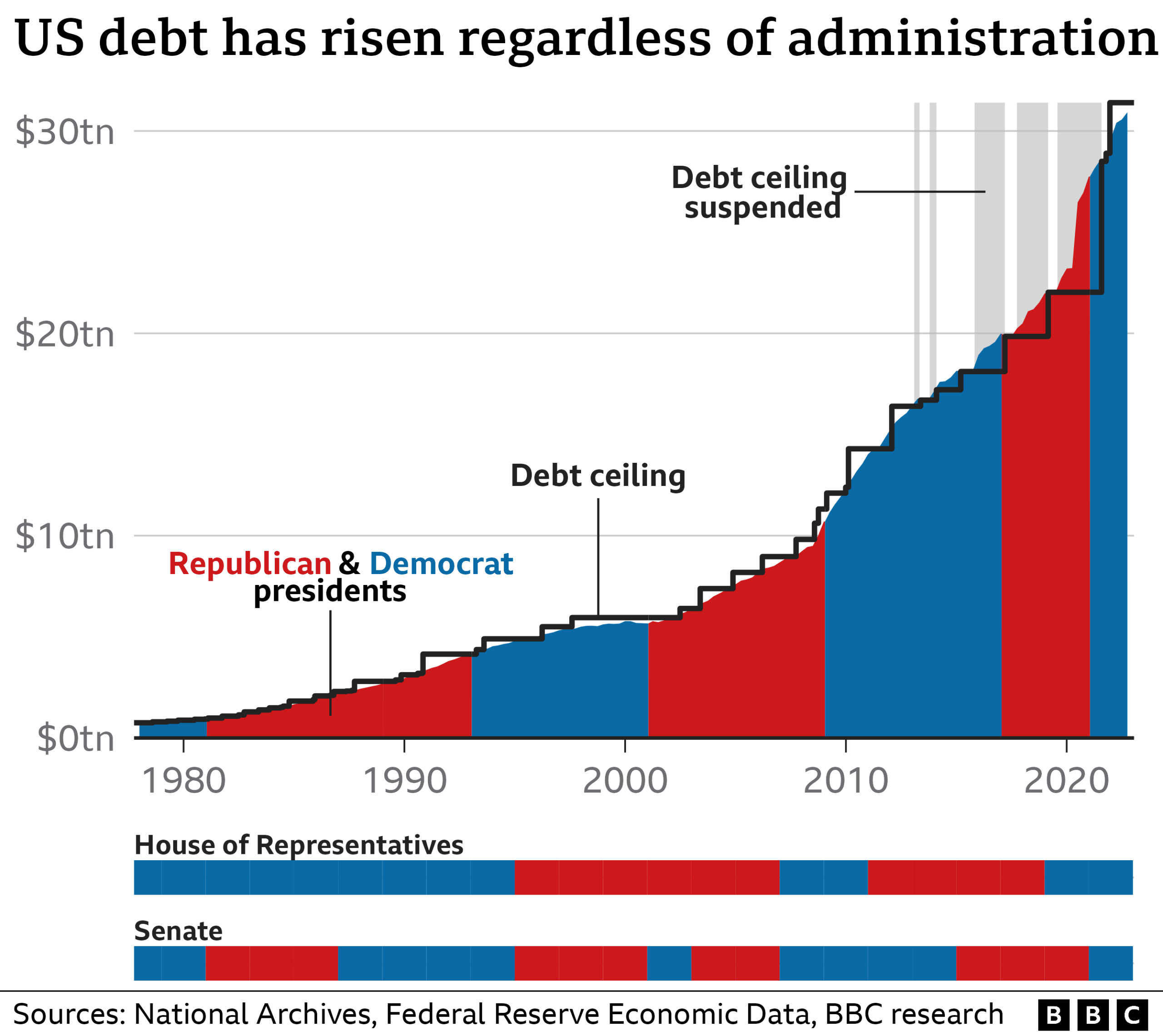

- U.S. Deficits: By the late 1960s, the U.S. was running large budget deficits (due to the Vietnam War and social programs) and trade deficits. More and more dollars were accumulating abroad, and foreign countries began to demand gold in exchange for their dollars, draining U.S. gold reserves.

The End of Gold: The Nixon Shock (1971)

The Bretton Woods system limped along for years, but the pressure on the U.S. dollar’s gold convertibility became unsustainable. On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon delivered a speech that effectively ended the international Gold Standard.

What Happened:

- Suspension of Gold Convertibility: Nixon announced that the U.S. would no longer convert dollars to gold for foreign central banks. This was the "Nixon Shock."

- Impact: This move immediately led to the floating of major world currencies. Exchange rates were no longer fixed but were determined by supply and demand in the foreign exchange markets.

The World Enters the Era of Fiat Money:

With the end of Bretton Woods, the world fully transitioned to a system of fiat money.

- Fiat Money: Currency that is not backed by a physical commodity like gold or silver, but by the government’s declaration (fiat) that it is legal tender. Its value comes from trust in the government and economy, and its acceptance for taxes and debts.

- Central Bank Control: This gave central banks unprecedented flexibility to manage their money supply, set interest rates, and respond to economic crises without being constrained by gold reserves.

Gold Standard: Pros and Cons (A Summary)

Let’s quickly summarize the arguments for and against the Gold Standard based on historical experience:

Potential Benefits (Proponents’ View):

- Limits Inflation: Prevents governments from printing too much money.

- Long-Term Price Stability: Can lead to predictable prices over long periods.

- Facilitates International Trade: Fixed exchange rates simplify cross-border transactions.

- Builds Confidence: Tying money to a tangible asset can foster trust in the currency.

Significant Drawbacks (Historical Reality):

- Inflexibility in Crises: Severely limits a central bank’s ability to stimulate the economy during recessions or depressions.

- Deflationary Bias: Can lead to harmful deflation if the economy grows faster than the gold supply.

- Vulnerability to Gold Supply: Economic stability depends on the unpredictable discovery of new gold.

- Spreads Crises: Fixed exchange rates can quickly transmit economic downturns from one country to another.

- Limits Economic Growth: Can stifle growth by restricting the money supply needed for an expanding economy.

- High Opportunity Cost: Holding vast gold reserves is expensive and unproductive.

Modern Monetary Policy and Crisis Management

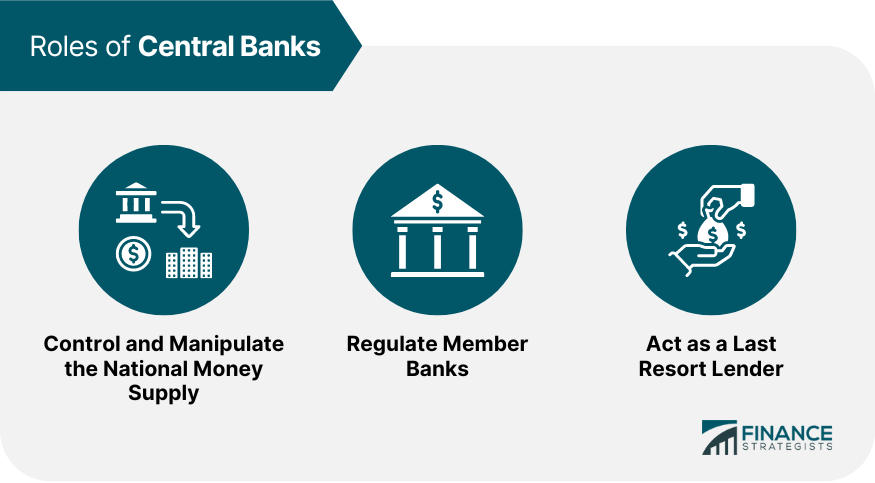

Today, most countries operate under a fiat money system with independent central banks (like the U.S. Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England). This system allows for much greater flexibility in managing economic crises.

How Modern Central Banks Respond to Crises:

- Interest Rate Adjustments: They can raise or lower interest rates to cool down an overheating economy (to fight inflation) or stimulate a sluggish one (to encourage borrowing and spending).

- Quantitative Easing (QE): In severe crises, they can buy government bonds or other assets to inject large amounts of money directly into the financial system, lowering long-term interest rates and encouraging lending.

- Currency Devaluation: A country can allow its currency to weaken, making its exports cheaper and more competitive globally, which can boost economic recovery.

- Lender of Last Resort: Central banks can provide liquidity to banks facing runs, preventing widespread financial collapse.

While modern economies still face crises (e.g., the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic), central banks have a much broader toolkit to respond, often preventing downturns from spiraling into depressions as severe as those experienced under the Gold Standard.

Could We Ever Go Back to the Gold Standard?

The idea of returning to the Gold Standard occasionally surfaces, particularly during times of economic uncertainty or high inflation. Proponents argue it would restore discipline and stability.

However, the vast majority of economists and policymakers believe a return is highly improbable and undesirable for several reasons:

- Lack of Gold: There simply isn’t enough gold in the world to back the current global money supply, which has expanded vastly with economic growth.

- Inflexibility: It would reintroduce the very inflexibility that crippled economies during past crises.

- Global Coordination: It would require unprecedented global cooperation to set fixed exchange rates and manage gold flows, which is extremely difficult to achieve.

- Economic Stagnation: It could lead to chronic deflation and slower economic growth.

History has shown that while the Gold Standard offered a certain kind of stability, it came at the cost of flexibility and often exacerbated economic downturns into severe crises.

Conclusion: Learning from the Golden Past

The story of the Gold Standard and historical economic crises is a powerful lesson in monetary economics. It highlights the delicate balance between stability and flexibility in managing a nation’s money supply. While the Gold Standard offered a perceived anchor, its rigid nature ultimately proved ill-suited to the dynamic and complex demands of modern economies, especially during times of crisis.

From the Great Depression to the unraveling of Bretton Woods, the historical record suggests that fixed, commodity-backed monetary systems can amplify economic shocks rather than absorb them. The shift to flexible, fiat money systems, managed by independent central banks, has provided governments with essential tools to navigate downturns, albeit with new challenges like managing inflation and financial bubbles.

Understanding the Gold Standard isn’t just about economic history; it’s about appreciating the evolution of our financial systems and the continuous quest to find the best way to manage money, promote prosperity, and mitigate the devastating impact of economic crises.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is "fiat money"?

A1: Fiat money is currency that is not backed by a physical commodity (like gold or silver) but by the government’s decree (fiat) that it is legal tender. Its value comes from the trust and confidence people have in the government and economy that issues it, and its acceptance for taxes and debts. Most currencies today (like the US dollar, Euro, Yen) are fiat money.

Q2: What is the difference between inflation and deflation?

A2:

- Inflation: A general increase in the prices of goods and services over time, leading to a decrease in the purchasing power of money. (Your money buys less than it used to).

- Deflation: A general decrease in the prices of goods and services, leading to an increase in the purchasing power of money. (Your money buys more than it used to). While it might sound good, widespread deflation can be very harmful to an economy, as it discourages spending and investment, and makes debts harder to repay.

Q3: Is the U.S. dollar still backed by gold?

A3: No, the U.S. dollar has not been backed by gold since 1971, when President Nixon officially ended its convertibility. It is now a fiat currency.

Q4: What is a central bank, and what is its role today?

A4: A central bank (like the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, or the Bank of England) is a national institution responsible for managing a country’s money supply, interest rates, and overall financial stability. Their main goals typically include maintaining price stability (controlling inflation), promoting full employment, and ensuring the stability of the financial system. They do this by setting interest rates, printing money, regulating banks, and acting as a "lender of last resort" during financial crises.

Post Comment