The Double-Edged Sword: Understanding the Role of Derivatives in Financial Instability

Financial markets are often seen as complex, almost mystical entities, and within them, few instruments generate as much debate and fascination as derivatives. These powerful financial contracts are designed for various purposes, from managing risk to speculating on future prices. However, their very nature – their leverage, complexity, and interconnectedness – has also made them central figures in episodes of profound financial instability, leading to crises that impact economies worldwide.

This article aims to demystify derivatives, exploring their legitimate uses while focusing on how they can, and have, contributed to moments of significant financial turmoil. We’ll break down complex concepts into easy-to-understand language, helping beginners grasp the critical role these instruments play in the health, or sickness, of our global financial system.

What Exactly Are Derivatives, Anyway? A Beginner’s Guide

Before diving into their role in instability, let’s understand what derivatives are. At their core, a derivative is a financial contract whose value is derived from an underlying asset, group of assets, or benchmark. Think of it like a bet or an insurance policy on something else. You’re not buying the asset itself, but rather a contract related to its future price or performance.

Common Underlying Assets Include:

- Stocks

- Bonds

- Currencies

- Commodities (oil, gold, corn)

- Interest rates

- Market indices (like the S&P 500)

- Even other derivatives!

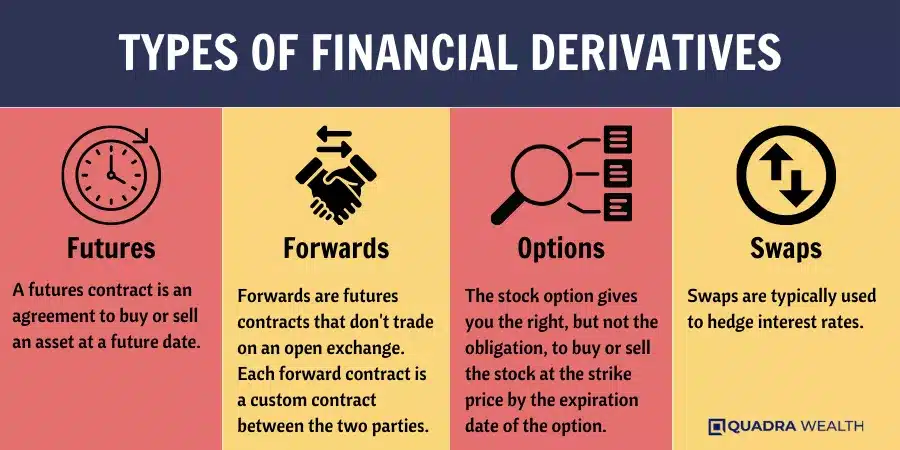

The Most Common Types of Derivatives:

-

Futures Contracts: An agreement to buy or sell an asset at a predetermined price on a specific date in the future. Both parties are obligated to complete the transaction.

- Example: An airline might buy a futures contract for jet fuel to lock in a price for fuel it will need in six months, protecting itself from potential price increases.

-

Options Contracts: Give the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specific price (the "strike price") on or before a certain date.

- Example: An investor might buy an option on a stock, hoping its price will rise. If it does, they can buy the stock at the lower strike price and immediately sell it for a profit. If it doesn’t, they only lose the small premium paid for the option.

-

Swaps: Agreements between two parties to exchange (swap) cash flows or other financial instruments over a period.

- Example: An interest rate swap might involve one company exchanging its fixed interest rate payments for another company’s floating interest rate payments, often to manage exposure to interest rate fluctuations.

-

Credit Default Swaps (CDS): A specific type of swap where one party pays a premium to another in exchange for protection against a specific credit event (like a default) on a debt instrument. It’s essentially insurance against a bond defaulting.

- Example: A bank holding corporate bonds might buy a CDS from another financial institution to protect itself if the company issuing the bonds goes bankrupt.

The "Good" Side: How Derivatives Should Work

It’s crucial to acknowledge that derivatives are not inherently evil. They serve several vital functions in healthy financial markets:

- Risk Management (Hedging): This is arguably their most important legitimate use. Companies and investors use derivatives to protect themselves from adverse price movements in assets they own or plan to acquire.

- Example: A farmer can sell futures contracts on their crop to lock in a price, protecting against a price drop before harvest.

- Price Discovery: The active trading of derivatives provides valuable information about future supply and demand expectations, helping to determine current and future prices of underlying assets.

- Market Efficiency: Derivatives can lower transaction costs and provide easier access to certain markets, making overall financial markets more efficient.

- Access to Markets: They allow investors to gain exposure to asset classes or strategies that might otherwise be inaccessible or too expensive.

However, the very features that make them powerful tools for hedging also make them potent instruments for speculation and, consequently, for amplifying financial instability.

The Dark Side: How Derivatives Fuel Financial Instability

When used excessively, improperly, or without sufficient oversight, derivatives can become a major source of financial instability. Their contribution to crises often stems from a combination of factors:

1. Leverage Magnification

One of the most appealing, yet dangerous, features of derivatives is leverage. Leverage allows investors to control a large amount of an underlying asset with a relatively small amount of capital. You put down a small initial investment (a "margin"), and the derivative contract controls a much larger value.

- How it works: If you buy a stock directly, a 10% price increase means a 10% gain on your invested capital. With a derivative, a 10% movement in the underlying asset could translate into a 100% or even 1000% gain (or loss) on your initial margin.

- The Problem: While leverage can amplify gains, it equally amplifies losses. A small adverse movement in the underlying asset can wipe out an investor’s entire initial capital and even lead to debts exceeding their initial investment. This forces investors to sell other assets to cover losses, creating a domino effect across markets.

- Systemic Impact: When many institutions are highly leveraged, a downturn can trigger a cascade of forced selling, plummeting asset prices, and widespread defaults, threatening the entire financial system.

2. Complexity and Opacity

Many derivatives, especially those traded Over-The-Counter (OTC) rather than on exchanges, are highly complex and customized.

- "Black Box" Effect: Their intricate structures can make it incredibly difficult for even sophisticated financial professionals, let alone regulators, to understand their true value, risks, and how they interact with other financial products.

- Valuation Challenges: In times of stress, when markets are volatile, accurately valuing these complex instruments becomes nearly impossible, leading to uncertainty and a lack of trust among market participants.

- Hidden Interconnectedness: Because OTC derivatives are private agreements, the web of who owes what to whom can be incredibly opaque. This lack of transparency means that the failure of one major participant can have unforeseen and far-reaching consequences throughout the financial system.

3. Systemic Risk and Interconnectedness

The global financial system is like a vast, intricate network. Derivatives, particularly OTC ones, are often the invisible threads connecting major financial institutions.

- Counterparty Risk: This is the risk that the other party to a contract (the "counterparty") will default on their obligations. In the opaque OTC derivatives market, assessing counterparty risk is challenging. If a major bank defaults on its derivative obligations, it can trigger a chain reaction, causing other institutions that relied on its payments to face solvency issues.

- "Too Big To Fail": Institutions with massive derivative exposures become "too big to fail" because their collapse would destabilize the entire system. This often leads to taxpayer-funded bailouts, as seen during the 2008 crisis.

- Credit Default Swaps (CDS) Example: While intended for hedging, CDS also became a speculative tool. Investors could buy "insurance" on bonds they didn’t even own, essentially betting on a company’s default. This created an incentive for some to actively profit from, or even contribute to, the downfall of the underlying entity, and vastly magnified the potential losses when defaults actually occurred.

4. Speculation and Market Bubbles

While hedging uses derivatives to reduce risk, speculation uses them to take on risk in pursuit of large profits.

- Exaggerated Price Swings: Derivatives provide a highly leveraged way to bet on market movements. This can attract enormous speculative capital, inflating asset prices beyond their fundamental value, leading to bubbles. When these bubbles burst, the leveraged positions in derivatives amplify the crash, leading to sharper declines.

- Herd Mentality: In speculative markets, participants often follow the crowd, exacerbating both the rise and fall of asset prices. Derivatives make it easier and cheaper to join the herd, accelerating market movements.

- Disconnect from Real Economy: Excessive speculation in derivatives can create a financial market that operates largely independently of the real economy, leading to distortions and misallocation of capital.

5. Lack of Transparency and Regulatory Gaps (Historically)

Historically, a significant portion of the derivatives market, especially OTC derivatives, operated with minimal regulatory oversight.

- Information Asymmetry: Regulators and the public often lacked clear visibility into the size, complexity, and risks embedded within these markets.

- Regulatory Arbitrage: Financial institutions could structure derivatives in ways that allowed them to circumvent existing regulations, exploiting loopholes and operating in less supervised corners of the market.

- Slower Adaptation: Financial innovation in derivatives often outpaced the ability of regulators to understand, assess, and regulate new products effectively.

Case Study: The 2008 Global Financial Crisis

The 2008 financial crisis stands as a stark example of how derivatives, particularly Credit Default Swaps (CDS) and Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs), played a central role in transforming a subprime mortgage problem into a global economic catastrophe.

- The Chain of Events:

- Subprime Mortgages: Banks issued mortgages to borrowers with poor credit histories, often with little documentation.

- Securitization & CDOs: These risky mortgages were bundled together and repackaged into complex financial products called Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs). Tranches (slices) of these CDOs were sold to investors, supposedly varying in risk. Rating agencies often gave these CDOs high ratings, masking their underlying risk.

- Credit Default Swaps (CDS): Financial institutions bought and sold CDS contracts related to these CDOs. Banks bought CDS as "insurance" against default, while hedge funds and other speculators bought CDS betting against the housing market.

- The Collapse: When the housing market collapsed and subprime borrowers started defaulting en masse, the value of the underlying mortgages plummeted. This triggered defaults on the CDOs.

- AIG’s Role: American International Group (AIG), a massive insurance company, had sold vast amounts of CDS protection on these CDOs without adequately hedging its own risk. When the CDOs defaulted, AIG faced billions in payouts it couldn’t cover. Its potential collapse threatened to trigger a systemic meltdown, as countless institutions were its counterparties in CDS contracts. The U.S. government was forced to bail out AIG to prevent a wider financial collapse.

- Derivatives’ Amplification: The crisis wasn’t caused solely by derivatives, but they acted as the primary amplifier. They spread the risk of subprime mortgages throughout the global financial system, made the interconnectedness opaque, and magnified losses due to leverage and speculative bets.

Mitigating Risks: Regulation and Future Outlook

The 2008 crisis spurred significant regulatory reforms aimed at making the derivatives market safer and more transparent:

- Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (U.S.): This landmark legislation, and similar efforts globally (like EMIR in Europe), introduced new rules for derivatives.

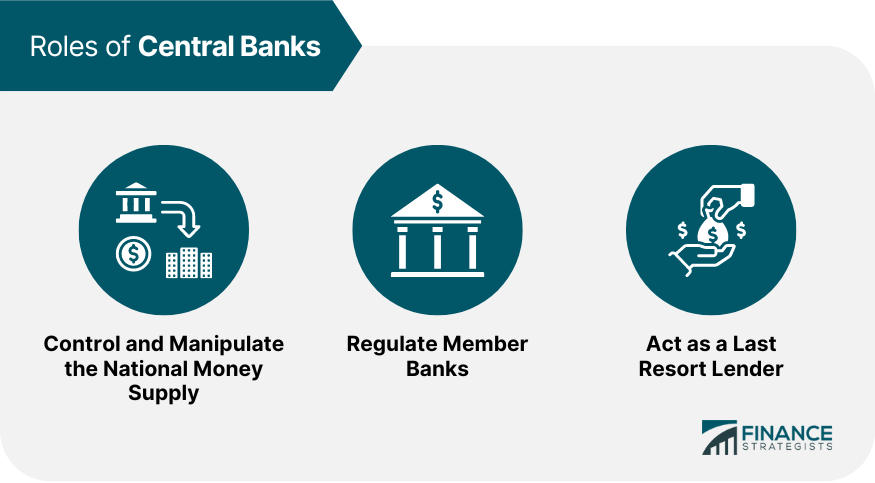

- Central Clearing: A key reform was the push for a significant portion of the OTC derivatives market to be cleared through central clearinghouses. A central clearinghouse acts as an intermediary, guaranteeing transactions and reducing counterparty risk by becoming the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer.

- Increased Transparency: Regulators now require more derivatives data to be reported, providing greater visibility into market activity and exposures.

- Higher Capital Requirements: Banks holding derivative positions are required to hold more capital, acting as a buffer against potential losses.

- Exchange Trading: More derivatives are now required to be traded on organized exchanges rather than privately OTC, further increasing transparency and standardization.

While these reforms have undoubtedly made the financial system more resilient, challenges remain. The derivatives market continues to innovate, and new complex products emerge. Regulators face the ongoing task of staying ahead of these innovations while balancing the need for market efficiency with the imperative of financial stability.

Conclusion: The Double-Edged Sword

Derivatives are undeniably a double-edged sword. On one side, they offer powerful tools for risk management, price discovery, and market efficiency, enabling businesses to hedge against uncertainties and investors to manage portfolios effectively. On the other side, their inherent characteristics – leverage, complexity, opacity, and potential for excessive speculation – can transform them into instruments of profound financial instability.

The lessons from past crises underscore the critical importance of robust regulation, transparent markets, and a deep understanding of the risks associated with these complex financial instruments. As the financial world continues to evolve, the ongoing challenge will be to harness the beneficial power of derivatives while effectively mitigating their potential to sow the seeds of the next financial crisis. For beginners and seasoned professionals alike, understanding this delicate balance is key to navigating the intricate landscape of modern finance.

Post Comment