The Business Cycle Explained: How Economic Crises Fit In (A Beginner’s Guide to Economic Ups & Downs)

Ever wonder why the economy seems to have good times and bad times, almost like a repeating pattern? One year, everyone is hiring, businesses are booming, and money feels plentiful. The next, job losses hit, companies struggle, and people tighten their belts. This fascinating, sometimes frustrating, rhythm is what economists call The Business Cycle.

Understanding the Business Cycle is crucial for anyone who wants to grasp how the economy works, from small business owners to everyday consumers. More importantly, it helps us understand how economic crises – like recessions or financial meltdowns – are not just random events, but often extreme, albeit painful, parts of this natural economic ebb and flow.

In this long-form guide, we’ll break down the Business Cycle into easy-to-understand pieces, explain its different phases, and show you exactly where those dreaded economic crises fit into the picture.

What Exactly is The Business Cycle?

Imagine the economy like a roller coaster. It goes up, it reaches a peak, it comes down, and then it bottoms out before starting its climb again. That’s essentially the Business Cycle in a nutshell.

The Business Cycle refers to the natural, cyclical ups and downs in economic activity over time. It’s measured by tracking changes in a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – the total value of all goods and services produced. When GDP is growing, the economy is expanding. When it shrinks, the economy is contracting.

It’s important to note that while it’s called a "cycle," it’s not perfectly predictable like the seasons. The length and intensity of each phase can vary significantly. However, the sequence of phases generally remains the same.

The Four Main Phases of The Business Cycle

Economists typically divide the Business Cycle into four distinct phases:

- Expansion (or Recovery/Growth)

- Peak

- Contraction (or Recession/Downturn)

- Trough

Let’s dive into what happens during each phase:

1. Expansion (The Good Times)

- What it feels like: This is the "good times" phase. Think of it as the economy climbing steadily up the roller coaster hill.

- Key Characteristics:

- Rising GDP: The economy is growing, producing more goods and services.

- Low Unemployment: Businesses are thriving and hiring more people, so fewer people are looking for jobs.

- Increased Consumer Spending: People feel confident about their jobs and future, so they spend more on everything from new cars to dining out.

- Business Investment: Companies invest in new equipment, factories, and technology to meet rising demand.

- Rising Wages & Profits: As demand for labor and products increases, both wages and company profits tend to rise.

- Optimism: There’s a general feeling of confidence and optimism about the economic future.

This phase can last for several years, creating periods of sustained prosperity.

2. Peak (The Top of the Hill)

- What it feels like: The economy has reached its maximum growth point. It’s the highest point on the roller coaster before the descent.

- Key Characteristics:

- GDP Growth Slows: While still positive, the rate of growth starts to decelerate.

- High Inflation Risk: With high demand and full employment, prices for goods and services can start to rise rapidly (inflation).

- Overheating Economy: Sometimes, the economy can become "overheated," meaning it’s growing too fast, leading to unsustainable price increases and potential bubbles in assets like housing or stocks.

- Capacity Constraints: Businesses might be operating at full capacity, struggling to produce more even with high demand.

- Subtle Warning Signs: At this point, economists might start to see subtle signs of potential trouble ahead, though they aren’t always obvious to the general public.

The peak is often short-lived and represents a turning point.

3. Contraction (The Slide Down)

- What it feels like: This is the downturn. The roller coaster starts its descent, often picking up speed.

- Key Characteristics:

- Falling GDP: Economic activity starts to slow down, and GDP begins to shrink.

- Rising Unemployment: Businesses reduce production, leading to layoffs and job losses. Fewer new jobs are created.

- Decreased Consumer Spending: People become more cautious, saving money and spending less, which further slows down the economy.

- Reduced Business Investment: Companies put a hold on expansion plans and new projects.

- Falling Wages & Profits: As demand drops, businesses may cut wages or experience lower profits.

- Pessimism: There’s a general feeling of uncertainty, fear, and pessimism about the economic future.

When a contraction is severe and lasts for a significant period (typically two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth), it is officially labeled a RECESSION.

4. Trough (The Bottom)

- What it feels like: This is the lowest point of the economic downturn. The roller coaster has hit the bottom and is preparing for its next climb.

- Key Characteristics:

- Lowest GDP Point: Economic activity hits its lowest point.

- Highest Unemployment: Job losses are at their peak, and unemployment rates are highest.

- Low Consumer Confidence: People are very cautious and worried.

- Reduced Inflation: With weak demand, inflationary pressures are often low or even negative (deflation).

- Potential Turning Point: While things might feel bleak, this is the point where the forces that will eventually lead to recovery begin to gather. Businesses might have cleared out excess inventory, prices might have stabilized, and conditions are ripe for a rebound.

From the trough, the economy typically begins a new recovery phase, which marks the beginning of the next expansion.

How Crises Fit In: When the Downturn Gets Extreme

Now, let’s address the elephant in the room: economic crises.

A crisis is not just any old contraction. Economic crises are unusually severe, rapid, and often widespread contractions in the Business Cycle. They are the moments when the roller coaster descent feels less like a smooth slide and more like a terrifying plunge, sometimes even derailing temporarily.

While all crises are contractions, not all contractions are crises. A mild recession is a contraction. A major financial meltdown leading to a deep, prolonged recession is a crisis.

What Causes These Extreme Downturns?

Crises rarely have a single cause. They are often the result of a combination of factors building up during the expansion phase, reaching a breaking point. Here are some common culprits:

-

1. Asset Bubbles Bursting: During long expansions, excitement can lead to over-speculation in certain assets (like housing, stocks, or even new technologies). Prices get pushed far beyond their real value. When investors realize this and start selling, the bubble bursts, leading to sharp price drops and panic selling.

- Example: The Dot-Com Bubble (early 2000s) and the US Housing Bubble (leading to the 2008 Financial Crisis).

-

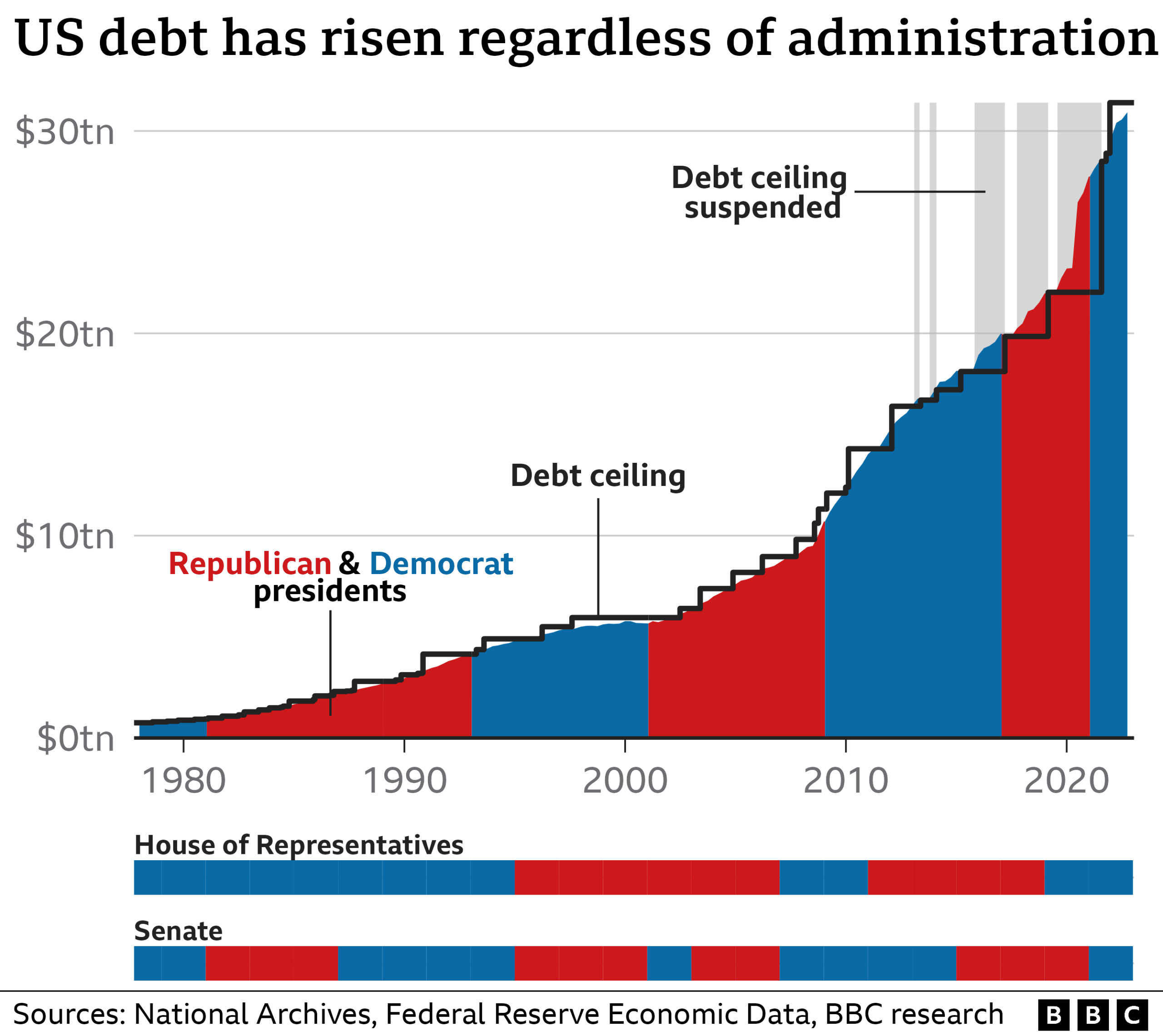

2. Excessive Debt: When individuals, businesses, or governments take on too much debt during good times, they become vulnerable. If interest rates rise or incomes fall, they struggle to repay, leading to defaults, bankruptcies, and a collapse of lending.

- Example: The Subprime Mortgage Crisis (part of the 2008 crisis) was fueled by excessive household debt.

-

3. Loss of Confidence: The economy runs on confidence. If consumers lose faith in the future, they stop spending. If businesses lose faith, they stop investing and hiring. This self-fulfilling prophecy can quickly spiral into a deep downturn.

- Example: The Great Depression saw a massive loss of public confidence.

-

4. External Shocks: Sometimes, events completely outside the normal economic system can trigger a crisis.

- Example: Natural disasters, pandemics (like COVID-19), wars, or sudden oil price spikes. These shocks disrupt supply chains, reduce demand, and create widespread uncertainty.

-

5. Policy Mistakes: While governments and central banks try to smooth out the cycle, sometimes their policies can inadvertently contribute to or worsen a crisis. This could be anything from raising interest rates too aggressively to insufficient regulation.

-

6. Systemic Risk: In interconnected financial systems, the failure of one major institution (like a large bank) can trigger a domino effect, leading to widespread collapse.

- Example: The collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 sent shockwaves through the global financial system.

Key Characteristics of a Crisis-Level Contraction:

- Severity: Much steeper and faster decline in GDP.

- Duration: Often longer-lasting than a mild recession, sometimes leading to a depression (a very long, severe, and widespread economic downturn).

- Widespread Impact: Affects almost all sectors of the economy and often spreads globally due to interconnectedness.

- Panic & Uncertainty: High levels of fear, market volatility, and a scramble for safety.

- Financial System Stress: Banks and financial institutions often face severe strain, sometimes requiring government bailouts.

The Impact of Crises: Why They Matter So Much

When a crisis hits, the consequences ripple through society, affecting almost everyone:

- Job Losses: Millions can lose their jobs, leading to financial hardship and stress for families.

- Business Failures: Companies, especially small and medium-sized ones, may go bankrupt.

- Lost Savings & Investments: Stock market crashes can wipe out retirement savings and investment portfolios.

- Reduced Spending: People spend less, which further harms businesses and slows down recovery.

- Increased Poverty & Inequality: The most vulnerable populations are often hit hardest.

- Social & Political Unrest: Economic hardship can lead to increased social tensions and political instability.

- Mental Health Strain: The stress of unemployment and financial insecurity can take a heavy toll on mental well-being.

Government & Central Bank Responses: Trying to Smooth the Ride

While crises are a part of the Business Cycle, governments and central banks don’t just sit idly by. Their main goal is to mitigate the severity and duration of contractions and prevent a full-blown crisis from spiraling out of control. They use two main tools:

1. Monetary Policy (Managed by the Central Bank, e.g., The Federal Reserve in the US)

- Lowering Interest Rates: Makes borrowing cheaper for businesses and consumers, encouraging spending and investment.

- Quantitative Easing (QE): The central bank buys government bonds and other assets to inject money directly into the financial system, lowering long-term interest rates and increasing liquidity.

- Lending to Banks: Providing emergency loans to banks to ensure they have enough money to lend and prevent a financial collapse.

The aim is to stimulate demand and make it easier for money to flow through the economy.

2. Fiscal Policy (Managed by the Government)

- Increased Government Spending: Investing in infrastructure (roads, bridges), education, or social programs creates jobs and stimulates demand.

- Tax Cuts: Leaving more money in people’s pockets encourages them to spend or invest.

- Unemployment Benefits & Stimulus Checks: Providing direct financial aid to individuals to support their spending and prevent destitution.

Fiscal policy directly injects money into the economy or leaves more money available for private spending.

These interventions are designed to shorten the duration of the trough and kickstart the next expansion. However, they are not without their own risks, such as increasing national debt or potentially leading to inflation if overused.

Learning from Crises & Building Resilience

While painful, economic crises often serve as harsh teachers. They expose weaknesses in the financial system, highlight unsustainable practices, and force governments and businesses to adapt.

- Regulatory Reforms: After a crisis, governments often implement new laws and regulations to prevent similar events from happening again (e.g., stricter banking regulations after 2008).

- Better Risk Management: Businesses and financial institutions learn to better assess and manage risks.

- Diversification: Individuals and investors learn the importance of not putting all their eggs in one basket.

- Personal Financial Preparedness: Crises underscore the importance of emergency savings, manageable debt, and diversified investments for individuals.

Conclusion: Understanding the Economic Rhythm

The Business Cycle is a fundamental concept in economics, illustrating the dynamic and ever-changing nature of our economies. From the boom of expansion to the bust of contraction, it’s a constant dance of growth and retreat.

Economic crises are not aberrations outside the Business Cycle; they are, in fact, severe manifestations of its contraction phase. They are the moments when the economic forces of supply and demand, confidence and fear, debt and investment, push the system to its breaking point.

By understanding the Business Cycle, its phases, and how crises fit in, you gain a clearer perspective on economic news, government actions, and even your own financial decisions. While we can’t perfectly predict the next turn of the cycle or prevent all crises, recognizing these patterns empowers us to prepare, adapt, and build more resilient economies for the future. The roller coaster will always have its ups and downs, but with knowledge, we can navigate the ride with greater confidence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About The Business Cycle & Crises

Q1: Is the Business Cycle predictable?

A: Not precisely. While the sequence of phases is generally consistent, the duration and intensity of each phase are highly unpredictable. Economists use various indicators to forecast, but exact timing and severity are hard to pinpoint.

Q2: What’s the difference between a Recession and a Depression?

A: A recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months. A depression is a much more severe and prolonged economic downturn, characterized by a massive fall in GDP, very high unemployment, and widespread business failures. The Great Depression of the 1930s is the most famous example.

Q3: Can governments prevent economic crises?

A: It’s extremely difficult, if not impossible, to prevent all crises. However, governments and central banks can use monetary and fiscal policies to try and mitigate their severity and shorten their duration. Their goal is to smooth out the peaks and troughs, making the cycle less volatile.

Q4: How long do the phases of the Business Cycle typically last?

A: There’s no fixed duration. Expansions can last for many years (e.g., the 1990s boom, the expansion after 2008). Recessions are typically shorter, often lasting a few quarters to a year or two. Peaks and troughs are generally very brief turning points.

Q5: How do international events affect the Business Cycle in my country?

A: In our highly globalized world, economies are deeply interconnected. A crisis in one major economy (like the US or China) can quickly spread to others through trade, financial markets, and investor confidence. Similarly, global events like pandemics or geopolitical conflicts can have widespread effects on business cycles worldwide.

Post Comment