Moral Hazard in Economic Crises: Understanding the Hidden Risk

Economic crises are often complex, with many factors contributing to their onset and severity. From housing market collapses to global pandemics, these events can shake the foundations of our financial systems and impact lives worldwide. While terms like "inflation," "recession," and "interest rates" are commonly discussed, there’s another crucial concept that plays a quiet, yet powerful, role behind the scenes: Moral Hazard.

For beginners, understanding moral hazard is key to grasping why some economic downturns happen, why certain institutions behave the way they do, and why governments face tough choices during times of crisis. Let’s break it down.

What Exactly is Moral Hazard? A Simple Explanation

At its core, moral hazard describes a situation where an individual or entity takes on more risk than they normally would because they are protected from the full consequences of that risk. It’s like having a safety net that encourages you to take bigger, bolder leaps.

Think of it this way:

- No Safety Net: If you’re walking on a tightrope without a net, you’ll be incredibly careful, taking small, precise steps. The full risk of falling is on you.

- With a Safety Net: If there’s a strong net directly below you, you might be tempted to try tricks, walk faster, or even jump a little. Why? Because you know that even if you fall, you won’t hit the ground. The hazard (risk of falling) changes your morals (behavior) because the consequences are mitigated.

In the world of economics and finance, moral hazard arises when one party’s behavior changes after they’ve entered into an agreement or when they’re insulated from the full costs of their actions.

Key Characteristics of Moral Hazard:

- Insulation from Risk: A party is protected, either partially or fully, from the downside of their decisions.

- Changed Incentives: Because the consequences are reduced, the incentive to act cautiously or prudently diminishes.

- Information Asymmetry (Often Present): One party (the one taking the risk) might have more information about their actions or intentions than the other party (the one bearing the cost of the risk).

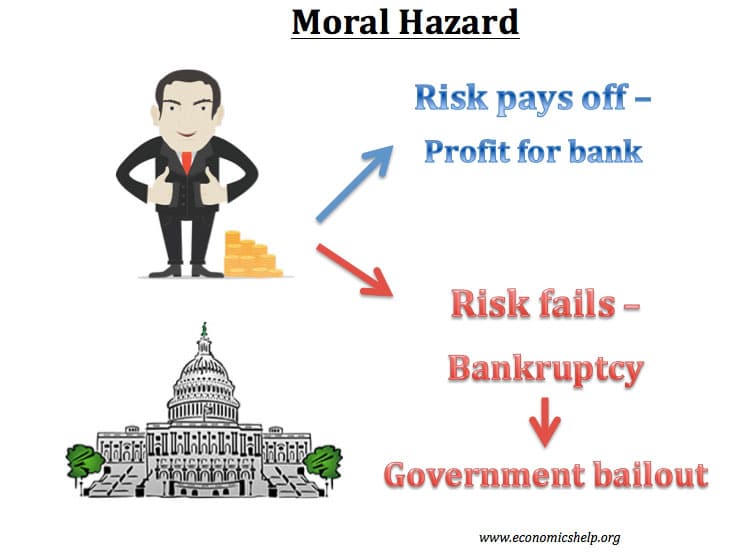

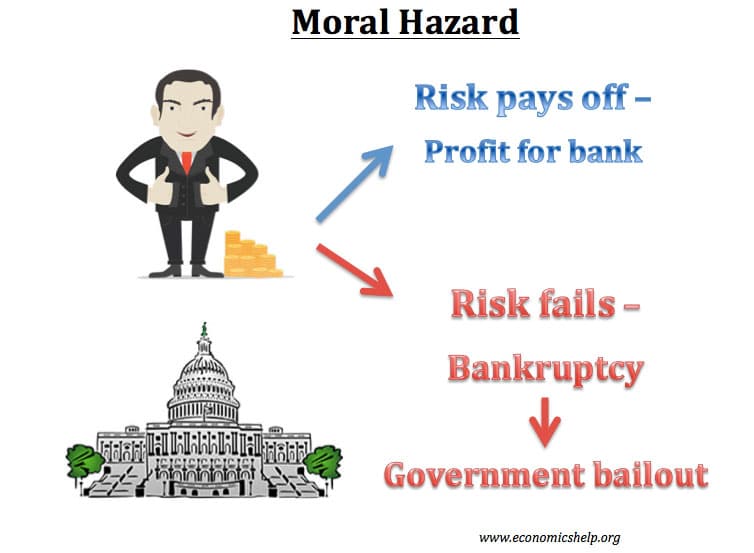

Moral Hazard in Action: The "Too Big to Fail" Dilemma

One of the most prominent and impactful examples of moral hazard in economic crises is the concept of "Too Big to Fail" (TBTF). This applies primarily to large financial institutions like major banks or insurance companies.

The TBTF Scenario:

- Systemic Importance: Some banks are so large and interconnected that their failure could trigger a domino effect, collapsing other banks, financial markets, and even the broader economy. This is known as systemic risk.

- Government Intervention Expectation: Because of this systemic risk, there’s a widespread belief (or expectation) that if one of these "too big to fail" institutions gets into deep trouble, the government will step in to rescue it with taxpayer money (a "bailout").

- The Moral Hazard Emerges: Knowing they are likely to be bailed out, these large institutions have less incentive to be careful. They might:

- Take on more risky investments.

- Lend money to less creditworthy borrowers.

- Maintain lower capital reserves than prudence would dictate.

- Engage in practices that generate high short-term profits but carry significant long-term risks.

Why be super cautious when you believe the government will catch you if you fall? This perceived safety net encourages behavior that might otherwise be considered reckless, increasing the overall risk in the financial system.

Historical Examples: Moral Hazard in Economic Crises

Moral hazard isn’t just a theoretical concept; it has played a significant role in major economic downturns throughout history.

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis: A Classic Case Study

The 2008 crisis, triggered by the collapse of the housing market and subprime mortgages, is a prime example of moral hazard at play.

- The Setup: For years leading up to 2008, many financial institutions (banks, mortgage lenders) engaged in aggressive lending practices, offering "subprime" mortgages to borrowers with poor credit histories and little ability to repay. These risky loans were then bundled into complex financial products and sold to investors.

- The Moral Hazard Connection:

- Lenders: Knew they could sell off these risky mortgages to other institutions, effectively transferring the risk. They were less concerned about the borrower’s ability to repay because the loan wouldn’t stay on their books.

- Investment Banks: Believed that even if the complex financial products they created (like Mortgage-Backed Securities and Collateralized Debt Obligations) went bad, their institutions were "too big to fail." They assumed the government would intervene to prevent a total collapse.

- Rating Agencies: Some agencies, paid by the very institutions whose products they were rating, gave inflated ratings to these risky products, creating a false sense of security.

- The Fallout: When the housing market collapsed and borrowers defaulted en masse, the value of these financial products plummeted. The "too big to fail" institutions faced massive losses. The U.S. government, fearing a complete economic meltdown, indeed stepped in with massive bailouts (e.g., the Troubled Asset Relief Program – TARP), seemingly confirming the moral hazard expectation.

Other Instances of Moral Hazard:

- Deposit Insurance: While vital for stability, government-backed deposit insurance (like FDIC in the U.S.) ensures that even if a bank fails, depositors won’t lose their savings (up to a certain limit). This can create a small degree of moral hazard, as depositors might be less concerned about the financial health of their bank. However, the benefits of preventing bank runs far outweigh this minor risk.

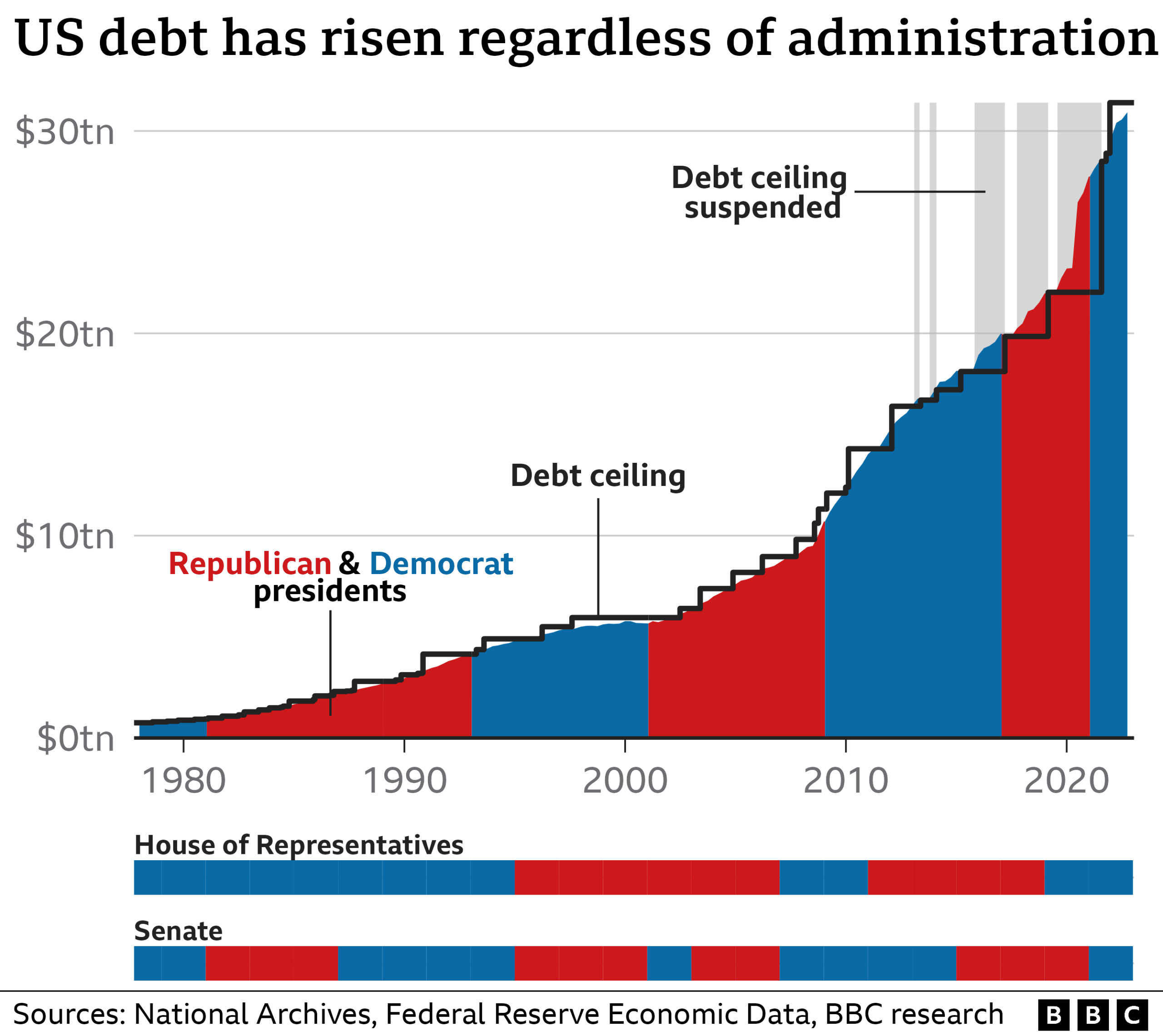

- International Bailouts: When countries face sovereign debt crises (e.g., Greece in the Eurozone crisis), international bodies like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the European Union often provide bailout packages. While these prevent immediate collapse, some argue they create moral hazard, as countries might be less disciplined in their fiscal policies if they expect to be rescued.

Why is Moral Hazard a Problem? The Consequences

The existence of moral hazard, especially on a large scale within the financial system, can have severe negative consequences:

- Increased Risk-Taking: It encourages institutions to take on excessive and imprudent risks, knowing that the potential losses will be absorbed by others (taxpayers, government).

- Misallocation of Resources: Capital flows to riskier ventures that might not be economically sound, rather than to productive, sustainable investments.

- Higher Costs for Taxpayers: When bailouts occur, the public bears the financial burden of private institutions’ failures.

- Erosion of Market Discipline: If institutions are always bailed out, the natural market forces that punish bad behavior (e.g., investors withdrawing funds, share prices falling) are weakened.

- Exacerbation of Future Crises: The "lesson" learned from a bailout can be that risky behavior pays off, setting the stage for even greater recklessness in the future.

- Unfairness: It creates a system where profits are privatized (kept by the institutions) but losses are socialized (borne by the public).

Addressing Moral Hazard: Solutions and Strategies

Policymakers and regulators are constantly grappling with how to mitigate moral hazard without stifling economic growth or triggering a crisis. Here are some common approaches:

- Stricter Regulation and Oversight:

- Higher Capital Requirements: Forcing banks to hold more of their own money (capital) as a buffer against losses means they have more skin in the game.

- Liquidity Requirements: Ensuring banks have enough readily available cash to meet short-term obligations.

- Stress Tests: Regular simulations to see how banks would fare under severe economic shocks.

- "Living Wills" (Resolution Plans): Requiring large, complex financial institutions to create detailed plans for how they could be safely dismantled in the event of failure, without resorting to a taxpayer bailout. This aims to make "too big to fail" institutions "resolvable."

- Bail-in Mechanisms: Instead of a government bailout, a "bail-in" involves forcing the institution’s creditors (bondholders, large depositors) to take losses to recapitalize the bank. This shifts the burden from taxpayers to those who invested in the bank.

- Clearer Rules for Government Intervention: Establishing transparent criteria and conditions under which government assistance might be provided, reducing the expectation of an automatic bailout.

- Increased Accountability: Holding executives and boards personally responsible for reckless behavior, potentially through fines, clawbacks of bonuses, or even criminal charges.

The Policymaker’s Tightrope Walk: Balancing Stability and Responsibility

Addressing moral hazard is a delicate balancing act for governments and central banks. On one hand, they want to prevent financial institutions from taking excessive risks that could destabilize the entire economy. On the other hand, they also need to maintain confidence in the financial system and prevent catastrophic collapses that could plunge millions into hardship.

If they promise never to bail out a large institution, they risk a more severe crisis if that institution fails. If they promise always to bail out, they encourage the very reckless behavior they want to prevent. The challenge lies in finding the right blend of regulation, accountability, and conditional support that promotes both stability and responsible behavior.

Conclusion: Moral Hazard – A Persistent Economic Challenge

Moral hazard is a fundamental concept in economics that explains how protection from risk can inadvertently encourage riskier behavior. In the context of economic crises, particularly the "too big to fail" phenomenon, it illustrates why governments often face unenviable choices between bailing out institutions to prevent collapse and letting them fail to teach a lesson about responsibility.

Understanding moral hazard helps us appreciate the complexities of financial markets, the rationale behind regulatory reforms, and the ongoing challenge policymakers face in designing systems that promote stability without fostering recklessness. As economies evolve, the dance between risk, responsibility, and the potential for moral hazard will undoubtedly continue to shape our financial future.

Post Comment