Monetary Policy in an Open Economy: How Interest Rates and Exchange Rates Drive Global Economics

Ever wondered how a central bank’s decisions about something seemingly abstract like "interest rates" can ripple through the entire global economy, affecting everything from the price of your imported goods to the cost of a foreign vacation? Welcome to the fascinating world of monetary policy in an open economy, where the interplay of interest rates and exchange rates becomes a critical dance for economic stability and growth.

For beginners, understanding these concepts can seem daunting, but fear not! This comprehensive guide will break down the complexities, making it easy to grasp how central banks steer their economies in an interconnected world.

What is Monetary Policy, Anyway? (A Quick Refresher)

At its core, monetary policy refers to the actions undertaken by a nation’s central bank (like the Federal Reserve in the U.S., the European Central Bank, or the Bank of England) to control the money supply and credit conditions to stimulate or restrain economic activity.

The primary goals of monetary policy typically include:

- Controlling Inflation: Keeping price increases at a stable, manageable level.

- Promoting Economic Growth: Encouraging investment, production, and job creation.

- Maintaining Full Employment: Ensuring as many people as possible who want to work can find jobs.

- Stabilizing Financial Markets: Preventing financial crises and ensuring smooth operation of banks and markets.

The Central Bank’s Main Tools:

While central banks have several tools, the most prominent one, especially for our discussion, is influencing interest rates.

- Setting the Policy Rate (e.g., Federal Funds Rate): This is the benchmark interest rate that banks charge each other for overnight lending. Changes to this rate cascade through the entire financial system, affecting borrowing costs for businesses and consumers alike.

- Open Market Operations: Buying or selling government bonds to inject or withdraw money from the banking system.

- Reserve Requirements: The percentage of deposits banks must hold in reserve, not lend out.

Understanding an "Open Economy"

Before diving into the intricate dance of interest rates and exchange rates, let’s clarify what an open economy means.

Unlike a hypothetical "closed economy" that operates in isolation, an open economy is one that engages in international trade and financial transactions with other countries. This means:

- Free Flow of Goods and Services: Imports and exports are common.

- Free Flow of Capital: Money can move relatively easily across borders for investment (e.g., buying foreign stocks, bonds, or building factories abroad).

This "openness" significantly complicates monetary policy, as domestic actions now have international repercussions, and international events can heavily influence domestic economic conditions.

The Critical Connection: Interest Rates and Exchange Rates

This is where the magic happens. In an open economy, interest rates and exchange rates are intimately linked through the mechanism of international capital flows.

Here’s the chain of events:

-

Interest Rate Differential: Investors, whether individuals, corporations, or large financial institutions, are always looking for the best returns on their money. If the interest rates offered in one country are significantly higher than in another (after accounting for risk), that country becomes a more attractive place to invest.

-

Capital Inflows and Outflows:

- Higher Domestic Interest Rates: Attract foreign capital. Foreign investors sell their own currency and buy the domestic currency to invest in the higher-yielding assets (like government bonds or bank deposits). This is a capital inflow.

- Lower Domestic Interest Rates: Encourage domestic investors to seek higher returns abroad, and make the country less attractive to foreign investors. Domestic investors sell their own currency to buy foreign currency for overseas investments. This is a capital outflow.

-

Impact on Exchange Rates:

- Capital Inflows (buying domestic currency): An increased demand for the domestic currency in the foreign exchange market causes its value to appreciate (get stronger). This means one unit of the domestic currency can buy more units of foreign currency.

- Capital Outflows (selling domestic currency): An increased supply of the domestic currency (as investors sell it) causes its value to depreciate (get weaker). This means one unit of the domestic currency buys fewer units of foreign currency.

In simple terms:

- Higher Interest Rates → Stronger Currency (Appreciation)

- Lower Interest Rates → Weaker Currency (Depreciation)

Monetary Policy in Action: How It Affects Everything

Now, let’s put it all together and see how a central bank’s decision on interest rates plays out in an open economy.

1. Expansionary Monetary Policy (Lowering Interest Rates)

When a central bank wants to stimulate the economy (e.g., during a recession or to combat low inflation), it implements an expansionary monetary policy. The primary tool for this is lowering its policy interest rate.

The Chain Reaction:

- Domestic Impact:

- Cheaper Borrowing: Lower interest rates make it cheaper for businesses to borrow for investment and for consumers to borrow for big purchases (like homes and cars).

- Increased Spending: This stimulates investment, consumption, and overall economic activity, leading to higher GDP and potentially more jobs.

- International Impact (via Capital Flows and Exchange Rates):

- Reduced Attractiveness for Foreign Capital: Lower domestic interest rates make the country less appealing for foreign investors seeking high returns.

- Capital Outflow: Foreign investors may pull their money out, and domestic investors may look for better returns abroad. Both actions involve selling the domestic currency and buying foreign currency.

- Currency Depreciation: This increased supply and reduced demand for the domestic currency leads to its depreciation (weakening).

- Trade Impact:

- Boosts Exports: A weaker domestic currency makes the country’s goods and services cheaper for foreign buyers. Exports become more competitive.

- Deters Imports: Foreign goods become more expensive for domestic consumers, reducing imports.

- Improved Trade Balance: This can help boost the trade balance (exports minus imports).

Summary of Expansionary Policy in Open Economy:

- Goal: Stimulate growth, combat deflation.

- Action: Lower interest rates.

- Effect: Capital outflow, currency depreciation, increased exports, decreased imports.

- Trade-off: Potential for imported inflation (as imports become more expensive).

2. Contractionary Monetary Policy (Raising Interest Rates)

When a central bank wants to cool down an overheating economy (e.g., to combat high inflation), it implements a contractionary monetary policy. The primary tool for this is raising its policy interest rate.

The Chain Reaction:

- Domestic Impact:

- More Expensive Borrowing: Higher interest rates make it more costly for businesses and consumers to borrow.

- Reduced Spending: This tends to slow down investment, consumption, and overall economic activity, helping to curb inflation.

- International Impact (via Capital Flows and Exchange Rates):

- Increased Attractiveness for Foreign Capital: Higher domestic interest rates make the country more appealing for foreign investors seeking better returns.

- Capital Inflow: Foreign investors bring their money in, and domestic investors are encouraged to keep their money at home. Both actions involve buying the domestic currency.

- Currency Appreciation: This increased demand for the domestic currency leads to its appreciation (strengthening).

- Trade Impact:

- Deters Exports: A stronger domestic currency makes the country’s goods and services more expensive for foreign buyers. Exports become less competitive.

- Boosts Imports: Foreign goods become cheaper for domestic consumers, increasing imports.

- Worsened Trade Balance: This can lead to a larger trade deficit (or smaller surplus).

Summary of Contractionary Policy in Open Economy:

- Goal: Curb inflation, cool overheating economy.

- Action: Raise interest rates.

- Effect: Capital inflow, currency appreciation, decreased exports, increased imports.

- Trade-off: Potential for slower economic growth and job losses.

Different Exchange Rate Regimes and Their Implications

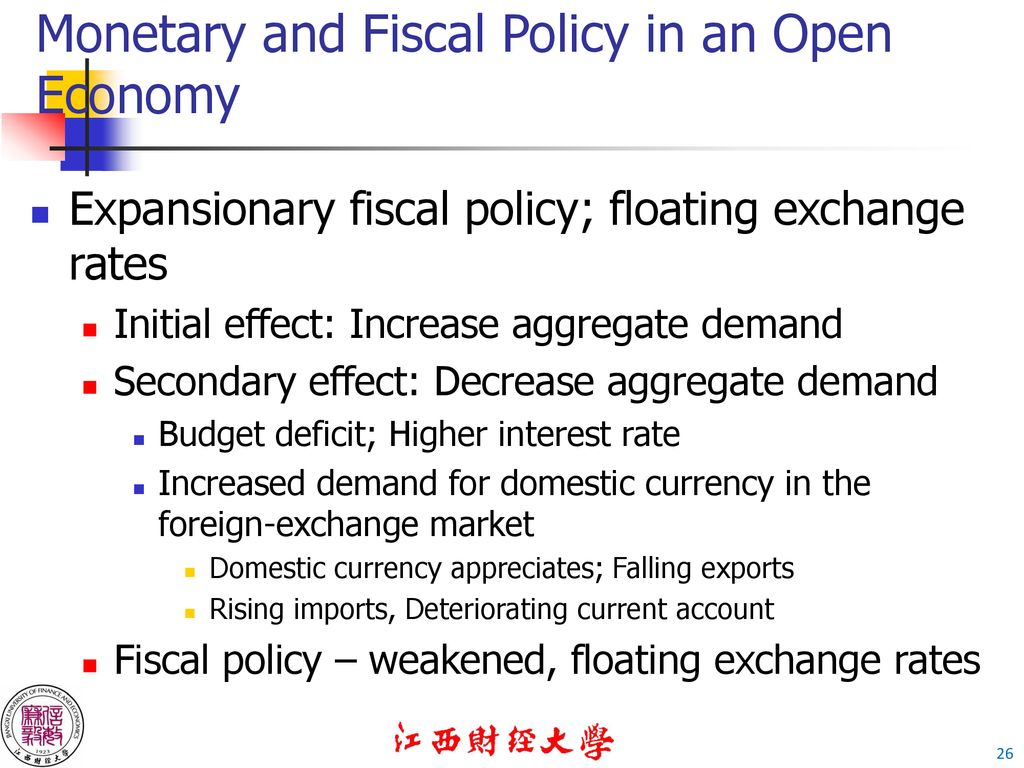

The way a country manages its exchange rate also profoundly affects how monetary policy works.

1. Floating Exchange Rate Regime

In a floating exchange rate regime, the value of the currency is determined by market forces (supply and demand) without significant intervention from the central bank. Most major developed economies (U.S., UK, Eurozone, Japan) operate under this system.

- Monetary Policy Freedom: Under a floating regime, the central bank has significant freedom to use interest rates to pursue domestic goals like inflation control or economic growth. If it raises interest rates, the currency appreciates, but the central bank doesn’t need to fight this appreciation. It allows the exchange rate to adjust.

- Automatic Stabilizer: The exchange rate can act as an "automatic stabilizer." For example, during a recession, if the central bank lowers interest rates, the currency depreciates, which helps boost exports and stimulate the economy.

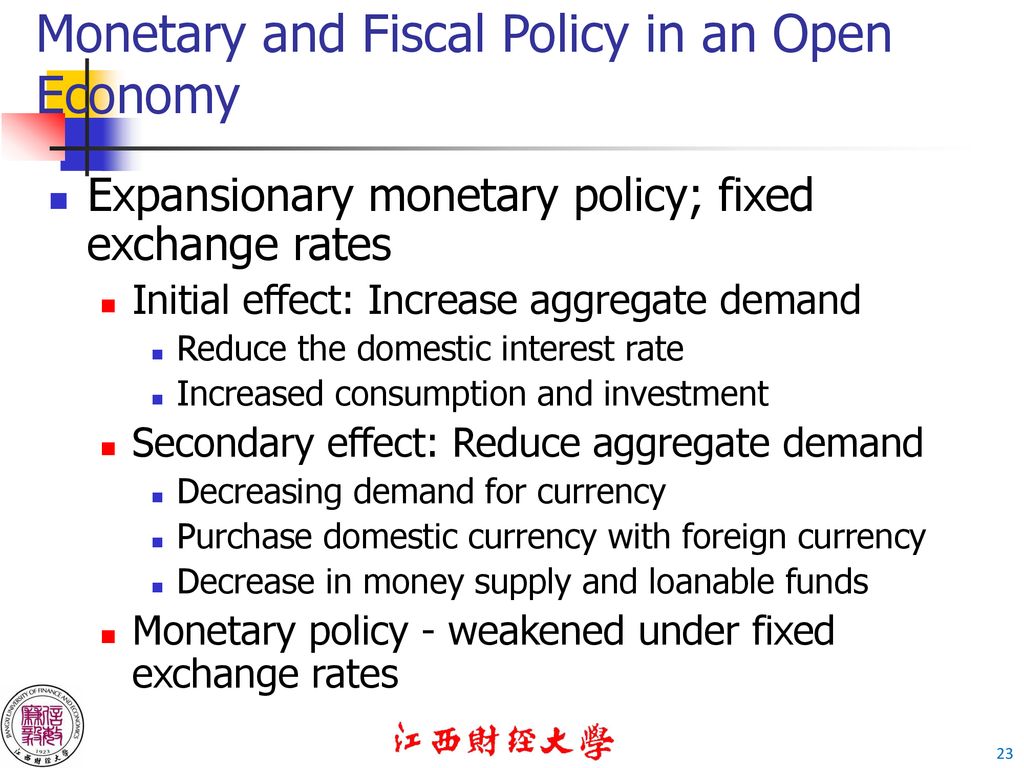

2. Fixed Exchange Rate Regime

In a fixed exchange rate regime, a country’s currency is pegged to another currency (e.g., the US dollar) or a basket of currencies at a predetermined rate. To maintain this peg, the central bank must actively intervene in the foreign exchange market.

- Loss of Monetary Policy Independence: This is the crucial trade-off. To maintain the fixed exchange rate, the central bank effectively loses its ability to set interest rates independently for domestic purposes.

- If the domestic interest rate is lower than the rate in the peg currency, capital will flow out, putting downward pressure on the domestic currency. To defend the peg, the central bank must sell foreign currency reserves and buy domestic currency, which contracts the domestic money supply and forces interest rates up, negating the original policy goal.

- Conversely, if domestic interest rates are higher, capital will flow in, putting upward pressure. The central bank must buy foreign currency and sell domestic currency, expanding the money supply and forcing interest rates down.

- Priority is the Peg: The central bank’s primary focus becomes maintaining the exchange rate, often at the expense of domestic economic goals like controlling inflation or unemployment.

The "Impossible Trinity" (or Trilemma)

This leads us to a fundamental concept in international finance: the Impossible Trinity (also known as the Trilemma). It states that a country cannot simultaneously achieve all three of the following:

- A Fixed Exchange Rate

- Free Capital Mobility (Free Flow of Capital)

- An Independent Monetary Policy

A country must choose two out of the three. For example:

- Fixed Exchange Rate + Free Capital Mobility: Must sacrifice independent monetary policy (e.g., many countries that have dollarized or peg their currency).

- Independent Monetary Policy + Free Capital Mobility: Must have a floating exchange rate (e.g., U.S., Eurozone, Japan).

- Fixed Exchange Rate + Independent Monetary Policy: Must impose capital controls (restrict capital flows) (e.g., China historically, though it’s gradually liberalizing).

Challenges and Trade-offs for Central Banks

Managing monetary policy in an open economy is a complex balancing act. Central banks face several challenges:

- Conflicting Goals: A policy aimed at controlling domestic inflation might lead to currency appreciation, which hurts exporters. Conversely, trying to boost exports through depreciation might fuel inflation.

- External Shocks: Global events (like a financial crisis in another major economy, or a sudden surge in global oil prices) can cause large capital flows or shifts in demand, making domestic policy difficult to manage.

- Global Spillovers: A large economy’s monetary policy decisions can have significant spillover effects on other countries, especially those with close trade and financial ties. For instance, a rise in US interest rates can draw capital away from emerging markets, putting pressure on their currencies and financial stability.

- Expectations: The effectiveness of monetary policy also depends heavily on how businesses and investors expect the central bank’s actions to influence future interest rates and exchange rates.

Conclusion: The Dynamic Dance Continues

Monetary policy in an open economy is a dynamic and intricate dance involving interest rates, capital flows, and exchange rates. A central bank’s decision to raise or lower interest rates doesn’t just affect borrowing costs at home; it sends ripples across global financial markets, influencing the value of its currency and, consequently, its international competitiveness and trade balance.

Understanding this interplay is crucial for anyone interested in how global economics work, how countries manage their economic health, and why the headlines about central bank meetings matter far beyond national borders. As our world becomes ever more interconnected, the importance of these relationships will only continue to grow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What’s the main difference between monetary policy in a closed vs. open economy?

A1: In a closed economy, monetary policy primarily affects domestic variables like inflation and output. In an open economy, it also significantly impacts international variables like exchange rates, capital flows, and the trade balance, adding layers of complexity and potential trade-offs.

Q2: How do interest rates affect my everyday life in an open economy?

A2: Directly, they affect your mortgage rates, car loans, and savings account returns. Indirectly, they influence the exchange rate, which impacts the price of imported goods (e.g., electronics, clothes) you buy, the cost of foreign travel, and even the competitiveness of the companies you work for if they export goods.

Q3: Does a strong currency always mean a strong economy?

A3: Not necessarily. A strong currency (appreciation) can make imports cheaper and help control inflation, which is good for consumers. However, it also makes exports more expensive and less competitive, potentially hurting domestic industries and jobs. A "strong" economy is one that is stable, growing, and has low unemployment, which isn’t solely determined by currency strength.

Q4: What is "quantitative easing" and how does it relate to interest rates and exchange rates?

A4: Quantitative Easing (QE) is an unconventional monetary policy where a central bank buys large quantities of government bonds or other financial assets to inject money directly into the economy. This aims to lower long-term interest rates (even when short-term rates are already near zero) and increase liquidity. Like conventional interest rate cuts, QE can lead to capital outflows and currency depreciation, making exports more competitive and potentially stimulating growth.

Q5: Who sets monetary policy?

A5: Monetary policy is set by a country’s central bank. Examples include the Federal Reserve (U.S.), the European Central Bank (Eurozone), the Bank of England (UK), the Bank of Japan, and the People’s Bank of China. These institutions are generally independent of the government to ensure their decisions are based on economic data rather than political pressures.

Post Comment