Mastering M&A Accounting: A Beginner’s Guide to Mergers and Acquisitions Financial Reporting

Imagine two companies, each a strong ship sailing independently. One day, they decide to join forces, either merging to become a mighty super-ship or one acquiring the other to expand its fleet. This exciting event in the business world is known as a Merger and Acquisition (M&A).

While the strategic reasons for M&A – like gaining market share, acquiring new technology, or achieving cost efficiencies – are often in the spotlight, there’s a crucial, often complex, backbone supporting these deals: M&A Accounting. It’s not just about adding two sets of financial statements together; it’s a specialized field that ensures the combined entity’s finances are accurately represented, compliant with regulations, and transparent to stakeholders.

For beginners, M&A accounting might seem like a labyrinth of complex terms and calculations. But fear not! This guide will demystify the core concepts, breaking down the essential principles of merger and acquisition accounting into easy-to-understand language.

What Exactly is M&A Accounting?

At its core, M&A accounting is the process of recording and reporting the financial impact of one company (the acquirer) taking control over another company (the acquiree). It’s governed by specific accounting standards, primarily ASC 805 in the United States (issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board – FASB) and IFRS 3 internationally (issued by the International Accounting Standards Board – IASB). Both standards mandate what’s known as the Acquisition Method.

Think of it this way: when you buy a house, you don’t just add its value to your checking account balance. You record the house as an asset, the mortgage as a liability, and your equity as the difference. M&A accounting applies a similar logic, but on a grander, more complex scale, dealing with entire businesses.

The main goal of M&A accounting is to provide a true and fair view of the combined entity’s financial position and performance after the transaction. This involves:

- Identifying the acquirer.

- Determining the acquisition date.

- Measuring the consideration transferred (what the acquirer paid).

- Recognizing and measuring the identifiable assets acquired and liabilities assumed at their fair values.

- Recognizing and measuring goodwill or a bargain purchase gain.

The Cornerstone: The Acquisition Method

The Acquisition Method is the required accounting standard for all business combinations. It replaces older methods like the "pooling-of-interests" method, which is no longer permitted.

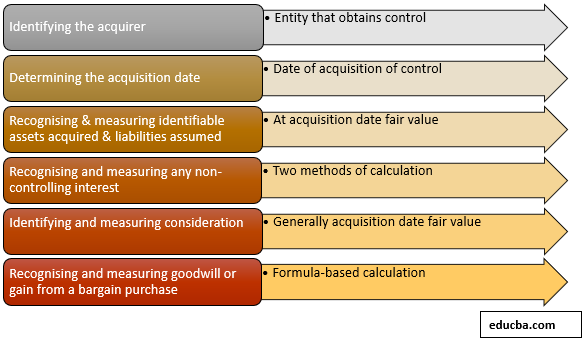

Here’s a breakdown of its key steps:

1. Identifying the Acquirer

This might seem obvious, but sometimes it’s not. The acquirer is the entity that obtains control of the other. Usually, it’s the one paying the cash or issuing its stock. Factors considered include:

- Which company initiates the acquisition.

- Which company’s management dominates the combined entity.

- Which company’s existing owners retain the largest portion of voting rights.

2. Determining the Acquisition Date

This is the date the acquirer obtains control of the acquiree. It’s crucial because it’s the point at which the fair values of the acquiree’s assets and liabilities are determined for accounting purposes. It also marks the date from which the acquiree’s financial results are consolidated into the acquirer’s financial statements.

3. Measuring the Consideration Transferred

This is the total cost of the acquisition. It’s what the acquirer "gave up" to gain control of the acquiree. This can include:

- Cash: The most straightforward form.

- Equity Instruments: Shares of the acquirer’s stock issued to the acquiree’s owners.

- Debt Instruments: Bonds or notes issued by the acquirer.

- Contingent Consideration: Promises to pay more in the future if certain conditions (like achieving specific revenue targets) are met. These are initially recognized at their fair value on the acquisition date.

All these components are measured at their fair value on the acquisition date. Fair value is essentially the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

The Heart of M&A Accounting: Purchase Price Allocation (PPA)

This is arguably the most critical and complex part of M&A accounting. Purchase Price Allocation (PPA) is the process of assigning the total consideration transferred (what the acquirer paid) to all the identifiable assets acquired and liabilities assumed from the target company at their fair values on the acquisition date.

Imagine you buy a whole pizza (the target company). You don’t just record "pizza." You identify the crust, the sauce, the cheese, the toppings, and assign a value to each based on its contribution to the overall pizza.

1. Recognizing Identifiable Assets Acquired and Liabilities Assumed

Before PPA, the target company’s balance sheet reflects its historical costs. In M&A accounting, these are adjusted to their current market values (fair values).

This involves:

- Tangible Assets: Land, buildings, machinery, equipment, inventory. These are revalued to what they would sell for today.

- Financial Assets & Liabilities: Accounts receivable, accounts payable, debt, investments. These are also re-measured to their fair values.

- Contingent Liabilities: Potential obligations whose existence will be confirmed only by the occurrence or non-occurrence of one or more uncertain future events not wholly within the control of the entity (e.g., a pending lawsuit). If probable and reliably measurable, these are recognized at fair value.

2. The Rise of Intangible Assets

One of the most significant aspects of PPA is the identification and valuation of intangible assets that may not have been on the target company’s books previously. These are assets that lack physical substance but have economic value.

Common examples of identifiable intangible assets include:

- Customer-Related Intangible Assets: Customer lists, customer relationships, order backlogs.

- Marketing-Related Intangible Assets: Trademarks, trade names, internet domain names, non-compete agreements.

- Contract-Based Intangible Assets: Licensing agreements, franchise agreements, servicing contracts, lease agreements.

- Technology-Based Intangible Assets: Patented technology, unpatented technology, software, databases, trade secrets.

- Artistic-Related Intangible Assets: Plays, literary works, musical works, photographs, video material.

These intangible assets are valued by specialized appraisers using various techniques (like discounted cash flow models) and then recorded separately on the acquirer’s balance sheet. They are then amortized (expensed) over their useful lives, just like tangible assets are depreciated.

3. The Enigmatic Goodwill

After all identifiable assets acquired and liabilities assumed have been recognized and measured at their fair values, there’s often a remaining amount. This leftover is known as Goodwill.

Goodwill is the excess of the consideration transferred (what was paid) over the fair value of the identifiable net assets acquired.

Formula:

Goodwill = Consideration Transferred – (Fair Value of Identifiable Assets Acquired – Fair Value of Liabilities Assumed)

Why does goodwill arise? It represents the premium the acquirer paid for elements that are not individually identifiable or separately measurable. This premium often reflects:

- Synergies: The expected benefits of combining the two companies (e.g., cost savings, increased revenue).

- Reputation: The target company’s strong brand name, loyal customer base, or excellent management team.

- Market Position: The target’s strategic advantage in its industry.

- Future Growth Potential: Unquantifiable future opportunities.

Crucially, goodwill is NOT amortized. Instead, it is subject to annual impairment testing. This means the company must regularly assess whether the value of the goodwill has decreased. If the fair value of the reporting unit (the part of the business to which the goodwill relates) falls below its carrying amount (including goodwill), an impairment loss must be recognized, which can significantly impact the acquirer’s profitability.

4. The Rare Bargain Purchase

What if the consideration transferred is less than the fair value of the identifiable net assets acquired? This rare situation is called a Bargain Purchase.

Formula:

Bargain Purchase Gain = (Fair Value of Identifiable Assets Acquired – Fair Value of Liabilities Assumed) – Consideration Transferred

A bargain purchase gain typically happens when the seller is under duress (e.g., financial distress, forced sale) and sells the company for less than its fair market value. Unlike goodwill, a bargain purchase gain is recognized immediately in profit or loss on the acquisition date.

Post-Merger Accounting: Beyond the Acquisition Date

The accounting doesn’t stop once the acquisition is complete and the PPA is done. The combined entity must continue to report its financial performance.

1. Consolidation

After the acquisition, the acquirer must consolidate the financial statements of the acquiree into its own. This means treating the acquiree as if it were part of the acquirer’s operations from the acquisition date onwards.

- All assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses of the acquiree are combined with those of the acquirer.

- Intercompany transactions (e.g., sales between the two entities) are eliminated to avoid double-counting.

- If the acquirer does not own 100% of the acquiree, a "non-controlling interest" (formerly minority interest) is recognized to represent the portion of the acquiree’s equity not owned by the acquirer.

2. Ongoing Reporting and Disclosures

The combined entity must continue to prepare financial statements (income statement, balance sheet, cash flow statement) and provide extensive disclosures about the acquisition, including:

- The nature and purpose of the business combination.

- The fair values of assets acquired and liabilities assumed.

- The amount of goodwill recognized and how it was determined.

- Information about contingent consideration.

- Pro forma financial information (showing what the combined results would have looked like if the acquisition had occurred earlier).

3. Goodwill Impairment Testing

As mentioned earlier, goodwill is not amortized but tested for impairment at least annually, or more frequently if events or changes in circumstances indicate that the carrying amount may not be recoverable. This involves comparing the fair value of the reporting unit (the segment of the business to which the goodwill is allocated) to its carrying amount. If the carrying amount exceeds the fair value, an impairment loss is recognized, reducing the value of goodwill on the balance sheet and decreasing net income.

Why is M&A Accounting So Crucial?

Beyond just compliance, sound M&A accounting provides immense value:

- Accurate Financial Reporting: It ensures that investors, creditors, and other stakeholders have a true picture of the combined entity’s financial health, performance, and future prospects.

- Informed Decision-Making: Proper valuation of assets and liabilities allows management to make better strategic decisions regarding integration, resource allocation, and future investments.

- Compliance and Transparency: Adhering to accounting standards like ASC 805/IFRS 3 ensures regulatory compliance, avoiding potential penalties and legal issues. Transparent reporting builds trust with the market.

- Risk Management: Identifying and valuing contingent liabilities and understanding the nature of goodwill helps in managing future financial risks.

- Tax Implications: While M&A accounting focuses on financial reporting, its outcomes significantly influence tax planning and liabilities, though tax accounting has its own specific rules.

Challenges in M&A Accounting

Despite its importance, M&A accounting is fraught with challenges:

- Valuation Complexities: Determining the fair value of various assets, especially intangible ones, can be subjective and requires significant judgment and expertise from appraisers.

- Integration Issues: Merging two accounting systems, processes, and cultures can be incredibly difficult, leading to data inconsistencies and operational bottlenecks.

- Data Availability and Quality: Obtaining reliable, detailed financial data from the target company during due diligence can be a hurdle, especially for privately held companies.

- Regulatory Scrutiny: Regulators closely examine M&A accounting, particularly the recognition of goodwill and intangible assets, to ensure no manipulation or misrepresentation.

- Post-Acquisition Adjustments: The initial PPA is based on estimates. Subsequent adjustments may be required as more information becomes available, leading to changes in reported financials.

- Goodwill Impairment Risk: The ongoing need to test goodwill for impairment introduces volatility into financial results, as large write-downs can occur if the acquisition doesn’t perform as expected.

Conclusion

Merger and Acquisition accounting is far more than a clerical task; it’s a strategic imperative. It lays the financial groundwork for successful business combinations, transforming two distinct entities into a cohesive, accurately represented financial whole. By understanding the core concepts – particularly the Acquisition Method, Purchase Price Allocation, the treatment of identifiable intangible assets, and the unique nature of goodwill – beginners can grasp the complexities and appreciate the vital role M&A accounting plays in the dynamic world of corporate growth and transformation.

For any company embarking on an M&A journey, investing in expert accounting advice and rigorous financial due diligence is not just recommended; it’s essential for long-term success and financial stability.

Post Comment