Mastering Economic Time Horizons: Short Run vs. Long Run in Economic Analysis

Ever wondered why some businesses can quickly ramp up production while others seem stuck with their current capacity? Or why some companies survive tough times by cutting corners, while others invest heavily for future growth? The answer often lies in understanding two fundamental concepts in economics: the Short Run and the Long Run.

These aren’t just arbitrary periods of time; they represent different levels of flexibility and decision-making power for businesses and even entire economies. Grasping this distinction is crucial for anyone looking to understand how markets work, how firms make decisions, and why economic policies have different impacts over varying timeframes.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll break down the Short Run and Long Run in economic analysis, making these core concepts easy for beginners to understand.

What’s the "Short Run" in Economics?

Imagine you own a popular coffee shop. Suddenly, there’s a huge surge in demand. What’s the quickest way you can make more coffee? You can hire more baristas, buy more coffee beans, or add another espresso machine. But what you can’t do overnight is build a bigger coffee shop, buy the building next door, or completely change your business model. This scenario perfectly illustrates the Short Run.

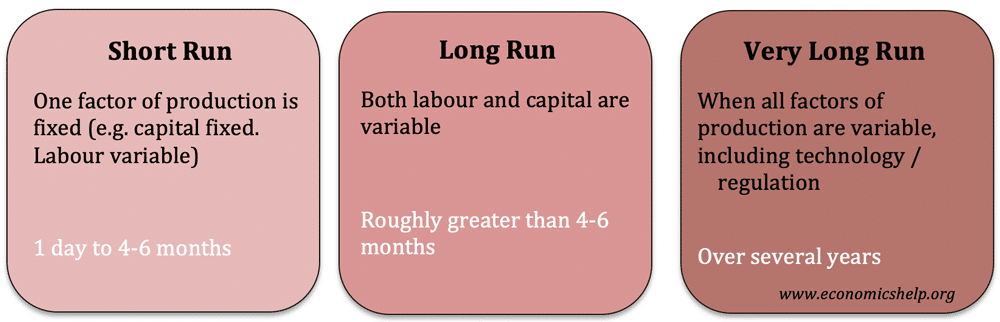

Definition: In economic analysis, the Short Run is a period of time where at least one factor of production (input) is fixed in quantity. This means a firm cannot easily change the amount of this input, even if it wants to increase or decrease its output significantly.

Key Characteristics of the Short Run:

- Fixed Inputs: There’s at least one input that cannot be changed. Common examples include:

- Factory size or building space: You can’t instantly expand or shrink your physical footprint.

- Large machinery or equipment: Installing new, specialized machines takes time and significant investment.

- Management structure or specialized staff: Training new high-level managers isn’t an overnight task.

- Variable Inputs: Other inputs can be changed relatively quickly to adjust output. These include:

- Labor: Hiring more workers (or asking existing ones to work overtime).

- Raw materials: Buying more coffee beans, flour, or steel.

- Utilities: Using more electricity or water.

- Limited Flexibility: Firms operate within the constraints of their fixed inputs. Their decisions primarily revolve around how best to use their existing capacity.

Implications for Businesses in the Short Run:

In the short run, a firm’s focus is on optimizing its use of variable inputs to maximize profit, given its fixed capacity. This often involves navigating concepts like the Law of Diminishing Returns, where adding more of a variable input (like labor) to a fixed input (like a factory) eventually leads to smaller and smaller increases in output per additional unit of the variable input.

What’s the "Long Run" in Economics?

Now, let’s revisit your coffee shop. After a year of consistent high demand, you decide it’s time for a major expansion. You look for a larger location, secure a loan to build a new, state-of-the-art shop, and even consider opening a second branch. You’re thinking about new technologies, different coffee suppliers, and perhaps even diversifying into pastries or merchandise. This is the Long Run.

Definition: The Long Run in economic analysis is a period of time long enough for a firm to vary all of its factors of production. In the long run, there are no fixed inputs; everything is considered variable.

Key Characteristics of the Long Run:

- All Inputs are Variable: A firm has complete flexibility to change the quantity of any input. This includes:

- Building new factories or offices: Expanding physical capacity.

- Purchasing new, more advanced machinery: Upgrading technology.

- Investing in research and development: Creating new products or processes.

- Entering new markets or exiting existing ones: Changing the scale and scope of operations.

- Complete Flexibility: Firms are not constrained by existing capacity. They can choose the most efficient scale of operation for their desired output level.

- Strategic Planning: Decisions in the long run are often strategic and involve significant investment and planning for the future.

Implications for Businesses in the Long Run:

In the long run, firms make decisions about their optimal scale of operation. They consider concepts like economies of scale (where increasing production leads to lower average costs) and diseconomies of scale (where production becomes too large and average costs start to rise). The goal is to choose the most efficient size and production method to achieve long-term profitability and sustainability.

The Crucial Difference: Not Just About Calendar Time!

One of the most common misconceptions is that the Short Run is a specific number of days, weeks, or months, and the Long Run is simply anything beyond that. This is incorrect!

The distinction between the Short Run and Long Run is not about a fixed period of chronological time, but rather about the flexibility of inputs.

- For a hot dog stand, the short run might be a few hours (they can’t easily buy a new cart in an hour). The long run might be a few days (they could buy a new cart).

- For a massive car manufacturing plant, the short run could be several months or even a year (they can’t build a new factory overnight). The long run could be many years.

Key Takeaway: The length of the "short run" and "long run" varies significantly depending on the industry, the type of firm, and the specific inputs being considered. It’s all about whether a firm has the ability to change all of its inputs.

Why Do These Concepts Matter? Applications in Economic Analysis

Understanding the Short Run and Long Run isn’t just an academic exercise; it has profound implications for how economists analyze various aspects of business and markets.

1. Production Decisions

- Short Run Production: Firms face the Law of Diminishing Returns. As more variable inputs are added to fixed inputs, the marginal output (additional output from one more unit of input) will eventually decrease. For example, adding too many workers to a small office will eventually lead to less, not more, productive work per person.

- Long Run Production: Firms consider Returns to Scale. This refers to how output changes when all inputs are increased proportionally.

- Increasing Returns to Scale (Economies of Scale): Output increases by a greater proportion than the increase in inputs (e.g., doubling inputs triples output).

- Constant Returns to Scale: Output increases by the same proportion as the increase in inputs.

- Decreasing Returns to Scale (Diseconomies of Scale): Output increases by a smaller proportion than the increase in inputs.

2. Cost Analysis

-

Short Run Costs:

- Fixed Costs (FC): Costs that do not change with the level of output (e.g., rent, insurance, loan payments for machinery). These exist only in the short run.

- Variable Costs (VC): Costs that change directly with the level of output (e.g., raw materials, hourly wages).

- Total Costs (TC): FC + VC.

- Average Fixed Cost (AFC): FC/Output. Declines as output increases.

- Average Variable Cost (AVC): VC/Output.

- Average Total Cost (ATC): TC/Output or AFC + AVC.

- Marginal Cost (MC): The additional cost of producing one more unit of output. In the short run, MC is heavily influenced by diminishing returns.

- Shape of Curves: Short-run cost curves (like ATC and AVC) are typically U-shaped due to the interplay of fixed costs and diminishing returns.

-

Long Run Costs:

- No Fixed Costs: In the long run, all costs are variable. A firm can adjust its scale to avoid any "fixed" constraints.

- Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) Curve: This curve is often called the "planning curve" or "envelope curve" because it shows the lowest possible average cost for producing any level of output when all inputs are variable. It’s formed by the minimum points of various short-run average cost curves (representing different plant sizes).

- Economies and Diseconomies of Scale: The LRAC curve is typically U-shaped, reflecting economies of scale (decreasing average costs as output expands) and then potentially diseconomies of scale (increasing average costs as output becomes too large).

3. Supply and Market Behavior

- Short Run Supply: Firms can only increase output by using their existing capacity more intensively. This often leads to a relatively inelastic supply curve, meaning supply doesn’t change much even with large price changes. If demand surges, prices might rise sharply because firms can’t quickly expand.

- Long Run Supply: Firms have time to build new factories, innovate, or even enter/exit the industry. This leads to a more elastic supply curve, meaning supply can respond significantly to price changes. If demand surges, new firms can enter, or existing ones can expand, eventually bringing prices back down.

4. Firm Strategy and Decision Making

- Short Run Strategy: Focuses on operational efficiency, managing variable costs, and maximizing profit given existing constraints. Decisions are tactical.

- Long Run Strategy: Involves significant investment decisions, research and development, market entry/exit, and adapting to long-term market trends. Decisions are strategic and aim for sustained growth and competitive advantage.

Short Run vs. Long Run: A Quick Comparison

| Feature | Short Run | Long Run |

|---|---|---|

| Input Flexibility | At least one input is fixed | All inputs are variable |

| Fixed Costs | Exist (e.g., rent, machinery payments) | Do not exist (all costs are variable) |

| Production Focus | Optimizing variable inputs with fixed capacity | Determining optimal scale of operation |

| Key Concept | Law of Diminishing Returns | Returns to Scale (Economies/Diseconomies) |

| Cost Curves | Separate Fixed, Variable, Total, Average, Marginal Costs | Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) Planning Curve |

| Supply Elasticity | Relatively inelastic | Relatively elastic |

| Business Decisions | Tactical, operational, adjustment | Strategic, investment, expansion/contraction |

| Time Horizon | Varies by industry; about flexibility | Varies by industry; about complete flexibility |

Real-World Examples to Solidify Understanding

Let’s look at how these concepts play out in different industries:

-

A Manufacturing Plant:

- Short Run: The factory building and the core assembly line machinery are fixed. To increase output, the plant can hire more workers, run extra shifts, or buy more raw materials. But they can’t quickly build a new wing or replace their entire robotic system.

- Long Run: The company can decide to build a second factory, invest in entirely new automated machinery, or even move production to a different country. All aspects of their production capacity can be changed.

-

A Software Development Company:

- Short Run: The office space, core development tools, and senior management team might be fixed. To meet a tight deadline, they can hire more junior developers (variable input) or pay existing staff overtime.

- Long Run: The company can lease a larger office, invest in a completely new IT infrastructure, develop proprietary software tools, or even restructure its entire organizational hierarchy.

-

A Local Restaurant:

- Short Run: The kitchen size, oven, and number of tables are fixed. To serve more customers, they can hire more chefs or waitstaff, buy more ingredients, or extend their opening hours.

- Long Run: The owner can decide to expand the restaurant, buy the building next door, invest in a bigger, more efficient kitchen, or even open a second restaurant location.

Common Misconceptions to Avoid

- "The Short Run is 6 months, the Long Run is anything over that." This is the biggest one. Remember, it’s about the flexibility of inputs, not a calendar date.

- "Fixed inputs are always tangible." Not necessarily. A highly specialized patent or a unique brand reputation could be considered a "fixed" asset in the short run if it can’t be easily replicated or changed.

- "In the long run, firms always make a profit." The long run simply allows for full adjustment. Firms might still incur losses in the long run if market conditions are unfavorable, or they fail to adapt efficiently. The long run is about the potential for optimal adjustment, not a guarantee of profit.

Conclusion: The Dynamic Nature of Economic Decisions

The concepts of the Short Run and Long Run are foundational to understanding how businesses operate and how markets respond to change. They highlight the different constraints and opportunities that firms face over varying time horizons.

- In the Short Run, firms are focused on optimizing their current operations, making the best use of what they have.

- In the Long Run, firms have the power to transform their operations, adjust their scale, and strategically position themselves for future success.

By distinguishing between these two critical timeframes, economists can better analyze costs, predict supply responses, and understand the strategic decisions that drive economic growth and change. So, the next time you hear about a company expanding or facing production bottlenecks, you’ll have a deeper appreciation for the economic time horizon they’re operating within.

Post Comment