Mastering Capital Budgeting Techniques: A Beginner’s Guide to Smart Investment Decisions

Ever wondered how big companies decide where to put their money for the long haul? Whether it’s building a new factory, developing a groundbreaking product, or upgrading essential technology, these aren’t spur-of-the-moment choices. They involve significant financial commitment and have a profound impact on a company’s future. This is where capital budgeting techniques come into play.

Capital budgeting is a critical process in financial management that helps businesses evaluate potential large-scale projects or investments. It’s about making smart, informed decisions on how to allocate scarce financial resources to projects that are expected to generate benefits over a long period. For beginners, the terminology can seem daunting, but once broken down, the core concepts are surprisingly intuitive.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll demystify capital budgeting techniques, breaking down each method with clear explanations, simple examples, and a look at their pros and cons. By the end, you’ll have a solid understanding of how businesses assess investment opportunities and make choices that drive long-term growth and profitability.

What Exactly Is Capital Budgeting?

At its heart, capital budgeting is the process of planning and managing a firm’s long-term investments. Think of it like a personal financial decision, but on a much larger scale. When you decide whether to buy a house, go to college, or invest in a retirement fund, you’re making a "capital budgeting" decision for your own life. You weigh the initial cost against the future benefits.

For businesses, capital budgeting involves:

- Identifying Investment Opportunities: Discovering potential projects that could benefit the company (e.g., expanding into a new market, purchasing new machinery, developing new software).

- Evaluating Projects: Analyzing the financial viability and strategic fit of these opportunities using various techniques.

- Selecting Projects: Choosing the most promising projects that align with the company’s goals and maximize shareholder wealth.

- Implementing and Monitoring: Putting the chosen projects into action and tracking their performance.

Why is it so important?

Capital budgeting decisions are crucial because they:

- Involve Large Sums of Money: These investments typically require significant upfront cash.

- Are Long-Term in Nature: The benefits and costs unfold over many years, often a decade or more.

- Are Often Irreversible: Once a factory is built or a new product line launched, it’s very difficult and costly to reverse the decision.

- Impact Future Profitability and Growth: Smart capital budgeting can lead to competitive advantages, increased revenue, and sustained success. Poor decisions can lead to financial distress.

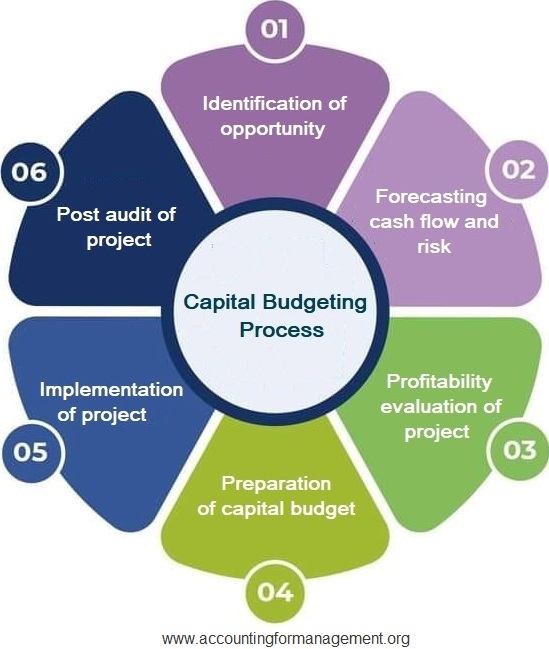

The Capital Budgeting Process: A Quick Overview

Before diving into the techniques, let’s briefly look at the typical steps involved in capital budgeting:

- Idea Generation: Brainstorming and identifying potential investment projects from various departments (marketing, production, research & development).

- Project Evaluation: Analyzing the financial feasibility of each project using the techniques we’re about to discuss. This involves forecasting cash flows and applying specific appraisal methods.

- Project Selection: Choosing the best projects based on the evaluation results, considering available funds, and strategic alignment.

- Implementation: Executing the chosen projects.

- Performance Review: Monitoring the project’s actual performance against initial forecasts and making adjustments as needed.

Key Capital Budgeting Techniques: Your Toolkit for Smart Investments

Capital budgeting techniques can be broadly categorized into two types:

- Non-Discounted Techniques: These methods do not consider the time value of money. They treat a dollar today the same as a dollar five years from now. While simpler, this is a significant limitation.

- Discounted Techniques: These methods do consider the time value of money, recognizing that money available today is worth more than the same amount in the future due to its potential earning capacity. These are generally considered more sophisticated and accurate.

Let’s explore each in detail.

I. Non-Discounted Capital Budgeting Techniques

These techniques are often used for a quick initial screening due to their simplicity.

1. Payback Period (PBP)

What it is: The Payback Period is the length of time it takes for an investment to generate enough cash flow to recover its initial cost. In simpler terms, it answers the question: "How long will it take to get my money back?"

How it works:

- For projects with even cash flows (same amount each period):

Payback Period = Initial Investment / Annual Cash Inflow - For projects with uneven cash flows: You calculate cumulatively until the initial investment is recovered.

Example:

Imagine a project costs $100,000 and is expected to generate $30,000 in cash flow each year.

Payback Period = $100,000 / $30,000 = 3.33 years

If another project costs $100,000 and generates cash flows of $20,000 (Year 1), $30,000 (Year 2), $40,000 (Year 3), and $50,000 (Year 4):

- Year 1: $20,000 recovered (remaining: $80,000)

- Year 2: $20,000 + $30,000 = $50,000 recovered (remaining: $50,000)

- Year 3: $50,000 + $40,000 = $90,000 recovered (remaining: $10,000)

- Year 4: Need $10,000 out of $50,000, so $10,000/$50,000 = 0.2 years.

Payback Period = 3 years + 0.2 years = 3.2 years

Decision Rule: Companies usually set a maximum acceptable payback period. Projects with a payback period shorter than this limit are accepted; otherwise, they are rejected. If choosing between projects, the one with the shortest payback period is often preferred.

Pros:

- Simplicity: Easy to calculate and understand.

- Liquidity Focus: Emphasizes how quickly cash is recovered, which is important for companies with limited liquidity.

- Risk Mitigation: Favors projects that recover initial investment quickly, potentially reducing risk exposure.

Cons:

- Ignores Time Value of Money: This is its biggest flaw. A dollar received today is treated the same as a dollar received years from now.

- Ignores Cash Flows After Payback Period: It completely disregards the profitability or cash flows generated once the initial investment is recovered. A project might have a short payback but then produce very little, while another has a longer payback but generates huge profits afterward.

- No Clear Decision Rule: The acceptable payback period is subjective and not based on maximizing wealth.

2. Accounting Rate of Return (ARR) / Return on Investment (ROI)

What it is: The Accounting Rate of Return (ARR), sometimes called Return on Investment (ROI), measures the average annual accounting profit generated by a project as a percentage of the initial investment or average investment. Unlike payback period, it focuses on profitability from an accounting perspective, not cash flow.

How it works:

ARR = (Average Annual Accounting Profit / Initial Investment) x 100%

Note: Accounting Profit is typically Revenue – Expenses – Depreciation, not cash flow.

Example:

A project costs $100,000 and is expected to generate an average annual accounting profit of $15,000.

ARR = ($15,000 / $100,000) x 100% = 15%

Decision Rule: If the ARR is higher than a pre-determined target rate, the project is accepted. If comparing projects, the one with the higher ARR is preferred.

Pros:

- Simplicity: Relatively easy to calculate and understand.

- Uses Accounting Profit: Familiar to managers who are used to financial statements and profit figures.

- Considers Entire Project Life: Unlike payback, it looks at the profitability over the project’s entire lifespan.

Cons:

- Ignores Time Value of Money: Like the payback period, this is a major drawback.

- Uses Accounting Profit, Not Cash Flow: Accounting profit can be manipulated and doesn’t represent actual cash generated, which is what truly matters for investment decisions.

- No Clear Decision Rule: The target ARR is subjective.

II. Discounted Capital Budgeting Techniques

These techniques are superior because they account for the time value of money. This fundamental concept states that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar promised in the future. Why? Because a dollar today can be invested and earn a return, growing into a larger amount over time. These methods use a "discount rate" (often the company’s cost of capital) to bring future cash flows back to their present value.

1. Net Present Value (NPV)

What it is: Net Present Value (NPV) is widely considered the most theoretically sound capital budgeting technique. It calculates the difference between the present value of all future cash inflows and the present value of the initial investment (and any future outflows). In essence, it tells you how much value a project adds to the company today.

How it works:

The formula looks complex, but the concept is simple:

NPV = (Present Value of Cash Flow 1) + (Present Value of Cash Flow 2) + ... + (Present Value of Cash Flow N) - Initial Investment

Each future cash flow is "discounted" back to its present value using a discount rate (also known as the required rate of return or cost of capital).

Present Value of a Future Cash Flow = Future Cash Flow / (1 + Discount Rate)^Number of Years

Example:

A project requires an initial investment of $100,000. It is expected to generate cash flows of $40,000 in Year 1, $50,000 in Year 2, and $30,000 in Year 3. The company’s required rate of return (discount rate) is 10%.

- PV of Year 1 Cash Flow: $40,000 / (1 + 0.10)^1 = $40,000 / 1.10 = $36,363.64

- PV of Year 2 Cash Flow: $50,000 / (1 + 0.10)^2 = $50,000 / 1.21 = $41,322.31

- PV of Year 3 Cash Flow: $30,000 / (1 + 0.10)^3 = $30,000 / 1.331 = $22,539.44

Total Present Value of Inflows = $36,363.64 + $41,322.31 + $22,539.44 = $100,225.39

NPV = Total Present Value of Inflows - Initial Investment

NPV = $100,225.39 - $100,000 = $225.39

Decision Rule:

- If NPV > 0 (Positive): Accept the project. It’s expected to add value to the company.

- If NPV < 0 (Negative): Reject the project. It’s expected to reduce company value.

- If NPV = 0: The project is expected to just break even in terms of value added (cover its cost of capital). Indifferent.

In our example, since NPV is $225.39 (positive), the project should be accepted.

Pros:

- Considers Time Value of Money: Its most significant advantage, providing a realistic assessment of value.

- Uses All Cash Flows: Considers all cash inflows and outflows over the project’s entire life.

- Clear Decision Rule: A positive NPV directly indicates that the project is expected to add value to the company, aligning with the goal of maximizing shareholder wealth.

- Absolute Value: Provides an actual dollar amount of value added.

Cons:

- Requires Discount Rate: Accurately determining the appropriate discount rate (cost of capital) can be challenging.

- Can Be Complex: Calculations are more involved than non-discounted methods, though financial calculators and software make it easier.

- Doesn’t Give a Rate of Return: It provides a dollar value, not a percentage return, which some managers prefer.

2. Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

What it is: The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is the discount rate that makes the Net Present Value (NPV) of a project exactly zero. In simpler terms, it’s the effective annual rate of return that the project is expected to generate over its life. It’s the maximum interest rate a company could afford to pay on the investment without losing money.

How it works:

Calculating IRR typically involves trial and error or financial calculators/software, as it’s the discount rate that solves the following equation:

NPV = 0 = (PV of Cash Flow 1) + (PV of Cash Flow 2) + ... - Initial Investment

Example (using our previous data):

Initial Investment: $100,000

Cash Flows: Year 1: $40,000, Year 2: $50,000, Year 3: $30,000

We are looking for the discount rate (IRR) that makes the NPV zero.

Using a financial calculator or software, the IRR for this project would be approximately 10.22%.

Decision Rule:

- If IRR > Cost of Capital (Required Rate of Return): Accept the project. The project is expected to earn a return higher than the company’s minimum acceptable rate.

- If IRR < Cost of Capital: Reject the project.

- If IRR = Cost of Capital: Indifferent.

In our example, if the company’s cost of capital is 10%, and the project’s IRR is 10.22%, then IRR > Cost of Capital, so the project should be accepted.

Pros:

- Considers Time Value of Money: Like NPV, it accounts for the time value of money.

- Intuitive: Expresses the return as a percentage, which is often easier for managers to understand and compare than an absolute dollar value.

- Uses All Cash Flows: Considers all cash flows over the project’s entire life.

- No External Rate Needed for Calculation: You don’t need to know the cost of capital before calculating the IRR (though you need it for the decision).

Cons:

- Can Have Multiple IRRs: For projects with unusual cash flow patterns (e.g., an initial outflow, then inflows, then another outflow), there might be more than one IRR, making the decision ambiguous.

- Assumes Reinvestment at IRR: This is a theoretical flaw. It assumes that intermediate cash flows generated by the project can be reinvested at the IRR itself, which might not be realistic, especially for very high IRRs. NPV assumes reinvestment at the cost of capital, which is generally more conservative and realistic.

- Issues with Mutually Exclusive Projects: When choosing between projects, IRR can sometimes lead to different decisions than NPV, especially if projects have different scales or cash flow patterns. NPV is generally preferred for mutually exclusive projects as it aims to maximize shareholder wealth directly.

3. Profitability Index (PI) / Benefit-Cost Ratio

What it is: The Profitability Index (PI), also known as the Benefit-Cost Ratio, measures the present value of future cash inflows for each dollar of initial investment. It essentially tells you "how much bang for your buck" you get.

How it works:

PI = Present Value of Future Cash Inflows / Initial Investment

Example (using our previous data):

Initial Investment: $100,000

Total Present Value of Inflows (from NPV calculation): $100,225.39

PI = $100,225.39 / $100,000 = 1.002

Decision Rule:

- If PI > 1: Accept the project. It means the present value of inflows is greater than the initial investment, indicating a positive NPV.

- If PI < 1: Reject the project.

- If PI = 1: Indifferent (NPV is zero).

In our example, since PI is 1.002 (greater than 1), the project should be accepted.

Pros:

- Considers Time Value of Money: Similar to NPV and IRR.

- Useful for Capital Rationing: When a company has a limited budget and multiple positive NPV projects, PI can help rank projects by how much value they generate per dollar invested, helping to choose the most efficient use of capital.

- Uses All Cash Flows: Accounts for all cash flows over the project’s life.

Cons:

- Requires Discount Rate: Like NPV, it depends on an accurate discount rate.

- Doesn’t Give Absolute Value: While it shows efficiency, it doesn’t tell you the total dollar value added, which NPV does. A project with a higher PI might have a lower NPV than a larger project with a slightly lower PI.

Factors Influencing Capital Budgeting Decisions

While the quantitative techniques provide a strong framework, real-world capital budgeting decisions are also influenced by qualitative factors:

- Risk: Projects vary in their riskiness. High-risk projects might require a higher expected return or a shorter payback period.

- Project Size: Larger projects typically involve more scrutiny and higher stakes.

- Strategic Fit: Does the project align with the company’s long-term vision, mission, and strategic goals?

- Regulatory and Environmental Factors: Compliance requirements, environmental impact, and potential legal issues can significantly affect project viability.

- Available Capital: The amount of funds a company has available for investment (capital rationing) can limit choices.

- Inflation: Changes in the purchasing power of money can affect the real value of future cash flows.

- Qualitative Benefits: Some projects might not have immediate financial benefits but offer strategic advantages like improved brand image, employee morale, or technological advancement.

Choosing the Right Capital Budgeting Technique

There’s no single "best" capital budgeting technique for every situation. In practice, companies often use a combination of methods to get a comprehensive view of a project’s viability.

- NPV is generally considered the most robust and theoretically sound method because it directly measures the value added to the company in dollar terms and aligns with the goal of maximizing shareholder wealth.

- IRR is popular for its intuitive percentage return, but its limitations with multiple IRRs and mutually exclusive projects need to be understood.

- Payback Period and ARR are useful for quick screening and liquidity concerns, but should rarely be the sole basis for major investment decisions due to their disregard for the time value of money.

- PI is excellent for ranking projects under capital rationing when a company has limited funds but multiple profitable opportunities.

Most sophisticated firms will calculate both NPV and IRR, and perhaps the payback period, for significant investments.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid in Capital Budgeting

Even with the right techniques, mistakes can happen. Be aware of these common pitfalls:

- Poor Cash Flow Forecasting: The techniques are only as good as the inputs. Overly optimistic or pessimistic cash flow predictions can lead to bad decisions.

- Ignoring Risk: Not adequately assessing and incorporating the risks associated with a project can lead to unexpected losses.

- Using the Wrong Discount Rate: An incorrect cost of capital can distort NPV and IRR calculations.

- Focusing Solely on One Metric: Relying exclusively on payback period or IRR without considering NPV can lead to suboptimal choices.

- Not Considering Qualitative Factors: Overlooking strategic alignment, environmental impact, or employee morale can lead to projects that are financially viable but harmful to the business in other ways.

- Failure to Review Post-Implementation: Not tracking and reviewing actual project performance against initial forecasts means missing opportunities to learn and improve future capital budgeting decisions.

Conclusion: Investing in the Future with Confidence

Capital budgeting techniques are indispensable tools for any business looking to make smart, long-term investment decisions. By understanding and applying methods like Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), Payback Period, and Profitability Index, companies can systematically evaluate opportunities, allocate resources effectively, and ultimately drive sustainable growth and profitability.

While the calculations might seem complex at first, the underlying logic is about making informed choices that maximize value. For beginners, grasping the concept of the time value of money and the core strengths and weaknesses of each technique is the first crucial step towards becoming a savvy financial decision-maker. Remember, capital budgeting isn’t just about numbers; it’s about strategically investing in the future of the business.

Post Comment