Leontief Paradox: Challenging Traditional Trade Theories and Unveiling Global Trade’s Nuances

Introduction: The Simple Idea of Trade vs. Complex Reality

For centuries, economists have sought to understand why nations trade. The basic idea seems simple: countries produce what they’re good at, then exchange it with others. This concept forms the bedrock of traditional trade theories, promising a clear path to mutual prosperity. But what happens when the real world throws a curveball, challenging these well-established ideas?

Enter the Leontief Paradox, a fascinating puzzle that emerged in the mid-20th century, shaking the foundations of prevailing international trade theory. Discovered by Nobel laureate Wassily Leontief, this paradox revealed that the United States, then considered the most capital-abundant nation, was actually exporting goods that were more labor-intensive and importing goods that were more capital-intensive. This finding flew directly in the face of the widely accepted Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) model, sparking decades of debate and profoundly enriching our understanding of global trade.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll dive deep into the Leontief Paradox, exploring:

- The traditional trade theory it challenged (the H-O model).

- Wassily Leontief’s groundbreaking research and its surprising findings.

- The various explanations proposed to resolve the paradox.

- Its lasting impact on economic thought and its relevance today.

Get ready to challenge your assumptions about international trade!

Understanding the Foundation: The Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) Model of Trade

Before we can appreciate the "paradox," we need to understand the "norm" it contradicted. The Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) model, developed by Swedish economists Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin in the early 20th century, was (and still is) a cornerstone of international trade theory.

The Core Idea of H-O:

The H-O model suggests that a country’s trade patterns are primarily determined by its factor endowments. What are factor endowments? Simply put, they are the resources a country has in abundance, specifically:

- Capital: Things like machinery, factories, infrastructure, and financial resources.

- Labor: The human workforce, including both skilled and unskilled workers.

- Land/Natural Resources: Arable land, mineral deposits, oil reserves, etc.

H-O’s Key Predictions:

The model makes two crucial predictions:

- Factor Abundance: Countries will tend to specialize in and export goods that intensively use the factor they have in abundance.

- Example: A country rich in capital (like Germany) would export goods that require a lot of capital to produce (e.g., high-tech machinery, complex electronics).

- Example: A country rich in labor (like Vietnam) would export goods that require a lot of labor to produce (e.g., textiles, apparel, basic manufactured goods).

- Factor Scarcity: Conversely, countries will tend to import goods that intensively use the factor they have in scarcity.

- Example: Capital-rich Germany might import labor-intensive goods.

- Example: Labor-rich Vietnam might import capital-intensive goods.

Why the H-O Model Made Sense (Initially):

At first glance, the H-O model seems very logical. If you have a lot of something, it’s cheaper for you to use it in production. So, it makes sense to build industries around your abundant resources and trade with others who have different strengths. For the United States, a nation that emerged from World War II with a massive industrial base and significant financial capital, the H-O model would clearly predict that the U.S. should be a major exporter of capital-intensive goods.

Enter Wassily Leontief: The Unexpected Discovery

In the early 1950s, Russian-American economist Wassily Leontief, a pioneer in input-output analysis (a method for analyzing interdependencies between different sectors of an economy), decided to put the H-O model to the test. He wanted to empirically verify its predictions using real-world data.

Leontief’s Research Method:

Leontief focused on U.S. trade data from 1947. He meticulously calculated the amount of capital and labor required to produce a given value of U.S. exports and a given value of U.S. imports (or, more precisely, the domestic production that would replace those imports). He used his sophisticated input-output tables to trace the capital and labor inputs through the entire production chain, not just the final assembly.

The Shocking Result – The Leontief Paradox:

What Leontief found was astonishing and completely counter-intuitive based on the H-O model. His analysis revealed that:

- U.S. Exports: Were, on average, more labor-intensive than U.S. imports. This meant that to produce $1 million worth of U.S. exports required more labor and less capital than to produce $1 million worth of goods that the U.S. imported.

- U.S. Imports: Were, on average, more capital-intensive than U.S. exports.

This finding was a paradox because the United States was undeniably the most capital-abundant nation in the world at that time. According to the H-O model, it should have been exporting capital-intensive goods and importing labor-intensive goods. Leontief’s findings suggested the exact opposite!

Unpacking the "Paradox": Why Did This Happen?

The discovery of the Leontief Paradox sent shockwaves through the economics community. If the most celebrated trade theory couldn’t explain the trade patterns of the world’s leading economy, what did that mean for economics? This prompted a flurry of research and debate, leading to several proposed explanations to reconcile the paradox with economic theory.

Here are some of the most prominent explanations:

-

1. The Role of Human Capital (The Most Accepted Explanation):

- Idea: Leontief’s measure of "labor" was too simplistic. It treated all labor as homogenous. However, U.S. labor was exceptionally skilled, educated, and productive compared to labor in many other countries.

- Explanation: Highly skilled labor (e.g., engineers, scientists, managers) can be considered a form of "human capital." Investing in education and training makes labor more productive, much like investing in machinery. If you account for this "human capital," then U.S. exports, while appearing labor-intensive, were actually intensive in skilled labor – a form of capital. Countries that imported from the U.S. might have had less skilled labor, making their "capital-intensive" goods (relative to their own labor) cheaper for the U.S. to import.

- Impact: This explanation significantly refined the H-O model, emphasizing that "labor" isn’t just a raw input but varies greatly in quality and embodied human capital.

-

2. Natural Resources and Factor Endowments:

- Idea: The U.S. was a large country with significant natural resources (land, minerals, etc.).

- Explanation: Many U.S. imports were natural resource-intensive goods (e.g., oil, raw materials, agricultural products from land-abundant countries). Extracting and processing these resources often requires substantial capital investment (e.g., mining equipment, drilling rigs). So, while the U.S. was capital-abundant overall, its imports were skewed towards capital-intensive resource-based goods. This might have made U.S. imports appear more capital-intensive than they truly were in a broader manufacturing context.

-

3. Trade Barriers and Distortions:

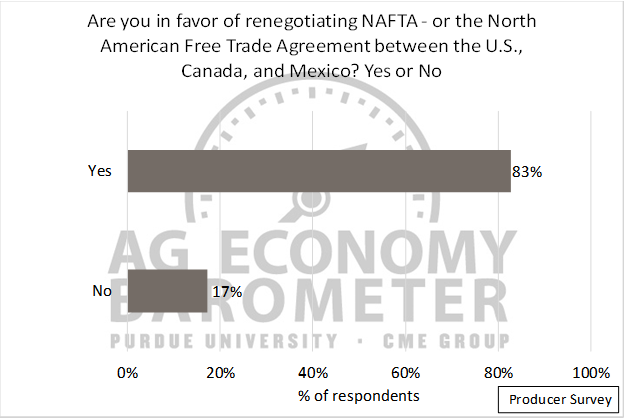

- Idea: The H-O model assumes free trade, but in 1947, trade was still subject to various tariffs, quotas, and post-war restrictions.

- Explanation: These barriers could distort trade patterns, preventing countries from fully specializing according to their comparative advantages. For instance, if the U.S. had high tariffs on certain capital-intensive imports, it might have encouraged domestic production of those goods, leading to a different observed trade pattern.

-

4. Demand Reversals (or Factor Intensity Reversals):

- Idea: It’s possible that the U.S. had a strong domestic demand for certain capital-intensive goods that it produced itself, while importing others. Or, that the factor intensity of production varied across countries.

- Explanation: If, for example, a good is capital-intensive to produce in one country but labor-intensive in another due to different production techniques or scales, it could confuse the overall picture. However, this explanation is generally considered less likely to explain the broad paradox.

-

5. Technology Differences:

- Idea: The U.S. had a technological lead over many other countries in 1947.

- Explanation: Superior technology could make U.S. labor highly productive, effectively making "less" labor achieve "more" output, blurring the lines of what truly constitutes "labor-intensive" production when comparing across nations with different technological levels.

-

6. Data Limitations and the "Rest of the World":

- Idea: Leontief’s data was from 1947, a unique post-war period. Also, his analysis focused on U.S. trade with the rest of the world as an aggregate, not individual countries.

- Explanation: The immediate post-war recovery meant many countries were rebuilding and might not have been operating under "normal" trade conditions. Additionally, aggregating "the rest of the world" might mask specific bilateral trade patterns that would better fit the H-O model.

The Enduring Impact and Legacy of the Leontief Paradox

While the initial shock of the Leontief Paradox was significant, it ultimately served as a powerful catalyst for progress in international trade theory rather than discrediting it entirely.

Key Contributions and Lasting Legacy:

- Refinement of the H-O Model: The paradox forced economists to look beyond simplistic definitions of capital and labor. The most enduring contribution was the recognition of human capital as a crucial factor endowment. This led to new models, like the Human Capital Model (or skill-based trade models), which predict that countries with abundant skilled labor will export skill-intensive goods, and vice-versa.

- Emphasis on Empirical Testing: Leontief’s work underscored the importance of empirical data and rigorous testing of economic theories. It showed that elegant theoretical models, no matter how logical, must be validated by real-world observations.

- Development of New Trade Theories: The paradox indirectly spurred the development of alternative and complementary trade theories that accounted for factors beyond simple factor endowments:

- Product Life Cycle Theory (Vernon): Explains how a product’s production might shift from the innovating country (often capital/skill-intensive) to other countries as it matures and becomes standardized.

- New Trade Theory (Krugman, Helpman): Emphasizes factors like economies of scale, imperfect competition, and consumer preferences in explaining trade patterns, especially among similar developed countries.

- Gravity Model: Focuses on factors like distance, economic size, and cultural ties between countries.

- Understanding Trade’s Complexity: The Leontief Paradox taught economists that international trade is far more nuanced than simple models suggest. It involves a complex interplay of factor endowments, technology, human capital, historical context, and policy choices.

- Relevance for Policy: By highlighting the importance of human capital, the paradox provided a strong economic argument for investments in education, training, and research & development as key drivers of a nation’s competitiveness in global trade.

Is the Leontief Paradox Still Relevant Today?

Absolutely! While the specific data from 1947 might be outdated, the lessons learned from the Leontief Paradox remain highly pertinent in the 21st century.

- Global Supply Chains: Today’s global supply chains fragment production processes across multiple countries. A "final good" might have components from dozens of nations, each contributing different factor intensities. This makes measuring overall capital/labor intensity incredibly complex, mirroring the challenges Leontief faced.

- The Rise of the Knowledge Economy: The increasing importance of intangible assets, intellectual property, and highly specialized skills (human capital) in modern economies makes the "human capital" resolution of the paradox more relevant than ever. Countries like the U.S. continue to excel in exporting highly knowledge-intensive and skill-intensive services and goods.

- Emerging Economies: As countries like China and India develop, their factor endowments are shifting. They are becoming more capital-abundant. Observing how their trade patterns evolve in response provides ongoing empirical tests for refined trade theories.

- Debate on "Fair Trade": Discussions about outsourcing, job displacement, and the impact of trade on wages often implicitly touch upon factor endowments and the intensity of capital vs. labor, making the underlying concepts of the paradox still relevant to public discourse.

- Continuous Refinement: Economists continue to refine trade models, incorporating factors like institutions, governance, and environmental considerations, building on the foundation laid by the challenges posed by Leontief’s work.

Conclusion: A Paradox That Enriched Economic Thought

The Leontief Paradox stands as a monumental moment in the history of international trade theory. Far from discrediting the Heckscher-Ohlin model entirely, it served as a crucial empirical challenge that forced economists to dig deeper, refine their assumptions, and develop more sophisticated explanations for global trade patterns.

What seemed like a contradiction at first ultimately led to a richer, more nuanced understanding of how nations interact economically. It highlighted the critical role of human capital, the complexities of real-world data, and the ever-evolving nature of global commerce.

The Leontief Paradox reminds us that economic theories are not static truths but dynamic frameworks that must constantly be tested against the ever-changing reality of the world. And in that ongoing intellectual journey, the "paradox" of 1947 remains a guiding star, illuminating the intricate dance of capital, labor, and innovation across international borders.

Post Comment