Diminishing Marginal Utility: Why More Isn’t Always Better (Understanding the Economic Principle of Satisfaction)

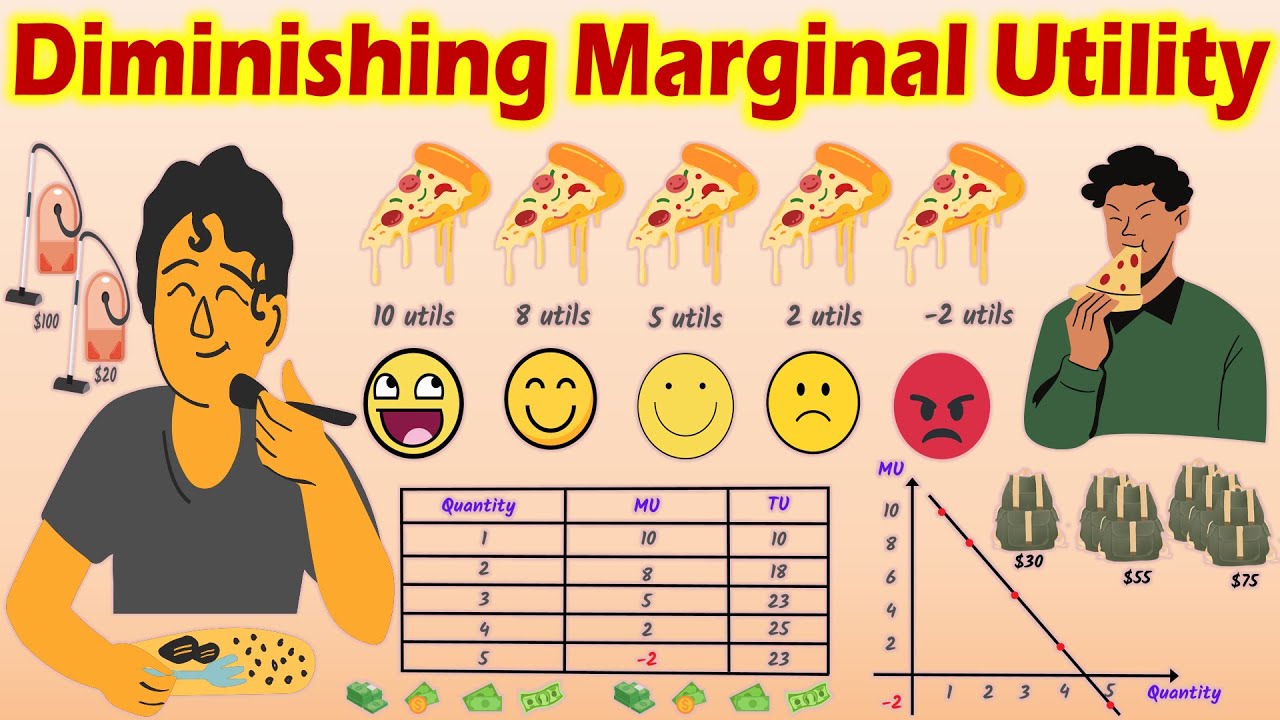

Have you ever craved something intensely, finally got it, and found the first taste or experience utterly delightful? Perhaps it was a slice of your favorite pizza, a brand new gadget, or a much-anticipated song. But what about the second, third, or even tenth helping? Did each subsequent unit bring the same thrill, the same level of satisfaction?

Chances are, it didn’t. This common human experience isn’t just a quirk; it’s a fundamental economic principle known as Diminishing Marginal Utility. It helps explain why our desires aren’t endless, why businesses price their products the way they do, and even why too much of a good thing can, well, stop being good.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll dive deep into Diminishing Marginal Utility, breaking down what it means, exploring real-world examples, and understanding why this seemingly simple concept has profound implications for our lives and the economy.

What is Utility? The Foundation of Satisfaction

Before we tackle "diminishing marginal utility," let’s first understand the core concept: Utility.

In economics, "utility" is a fancy word for the satisfaction, happiness, or value that a consumer gets from consuming a good or service. It’s subjective – what brings high utility to one person might bring less to another.

Think of utility as a measure of how much "goodness" something provides you.

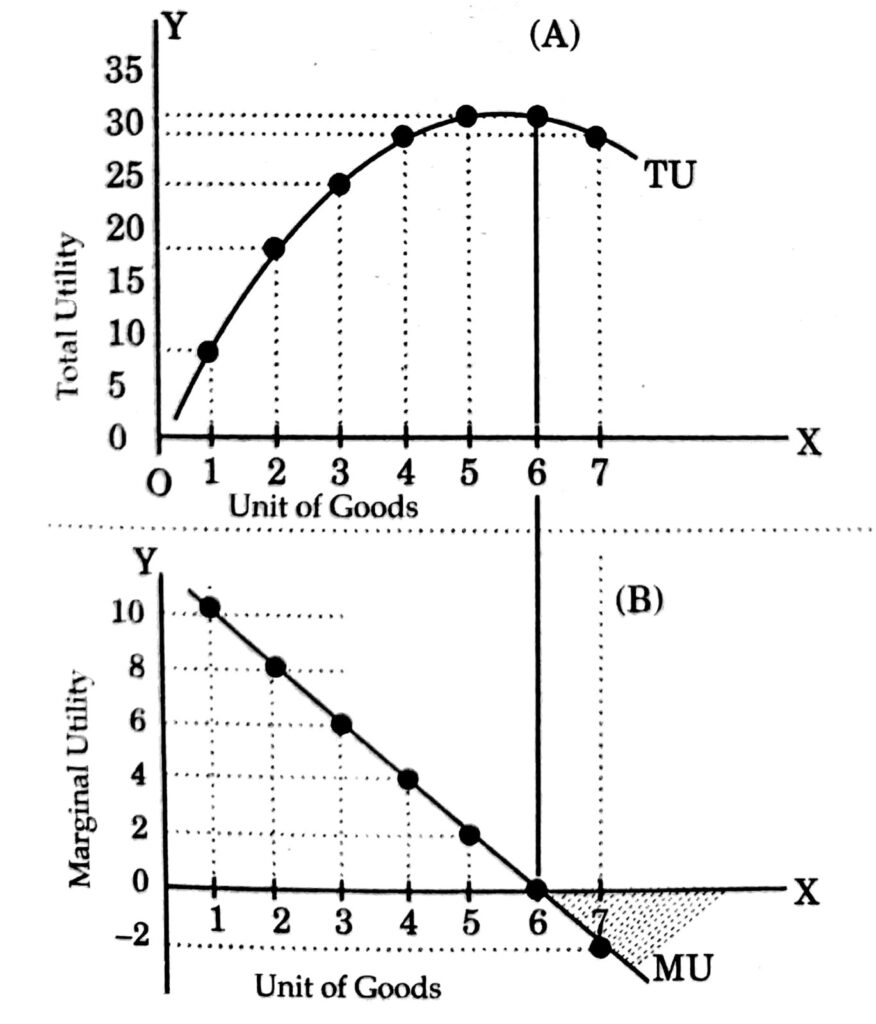

- Total Utility: This refers to the overall satisfaction you get from consuming a certain quantity of a good or service. For instance, the total satisfaction from eating three slices of pizza.

- Marginal Utility: This is the key term for our discussion! Marginal utility is the additional satisfaction or extra utility you gain from consuming one more unit of a good or service. It’s the "extra goodness" from that next slice of pizza, or that next hour of watching your favorite show.

The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility Explained

Now, let’s put it all together. The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility states that:

As a person consumes more and more units of a specific good or service, the additional satisfaction (marginal utility) gained from each subsequent unit tends to decrease.

In simpler terms: The more you have of something, the less extra satisfaction you get from having even more of it. The first bite of that pizza is amazing. The second is still great. The third? Good. The fourth? You’re getting full. The fifth? You might start feeling uncomfortable. The sixth? You might even feel sick!

Key characteristics of Diminishing Marginal Utility:

- It’s about additional satisfaction: The total satisfaction might still be increasing (you’re happier with three slices than one), but the rate at which it’s increasing slows down.

- It eventually turns negative: If you consume too much, the marginal utility can even become negative, meaning that consuming another unit actually decreases your total satisfaction (like feeling sick from too much pizza).

- It applies to most goods and services: While there might be rare exceptions, this law holds true for the vast majority of things we consume.

Real-World Examples of Diminishing Marginal Utility

This principle isn’t just theory; it’s something we experience every day. Let’s explore some common examples:

1. Food and Drink (The Classic Example)

- Water on a Hot Day: You’re parched. The first glass of water is incredibly refreshing, providing immense utility. The second glass is still very good. By the fifth or sixth glass, you’re probably no longer thirsty, and any more water might just make you feel bloated. The marginal utility of each additional glass has steadily diminished.

- Your Favorite Dessert: That first spoonful of chocolate cake is pure bliss. The second, third, and fourth spoonfuls are still enjoyable. But eventually, you reach a point where another spoonful isn’t as satisfying, and you might even start to feel a little queasy.

2. Possessions and Gadgets

- New Shoes: Buying your first pair of stylish, comfortable shoes brings a significant boost in satisfaction. A second, different pair might still be very useful and bring satisfaction. But buying your tenth or twentieth pair of shoes, especially if they’re very similar, will likely bring much less additional joy or utility than the first. You already have plenty of options!

- Smartphones/Laptops: Upgrading from an old, slow phone to a brand-new, lightning-fast model provides a huge jump in utility. But upgrading from last year’s model to this year’s, which might only have minor improvements, provides far less marginal utility. You’re already getting most of the functionality you need.

3. Entertainment and Experiences

- Listening to a Song: The first few times you hear a new favorite song, it’s exhilarating. You might put it on repeat. But listen to it 50 times in a row, and the marginal utility will plummet. It might even become annoying.

- Watching a Movie: Enjoying a great movie for the first time is a high-utility experience. Watching it a second time might still be enjoyable, picking up on new details. But watching it for the tenth time will likely offer very little additional enjoyment, and you might even get bored.

4. Money (The Paradox of Wealth)

This is a profound example often used to explain why simply accumulating more wealth doesn’t necessarily lead to endless happiness.

- The First Dollar vs. The Millionth Dollar: For someone with no money, the first dollar earned can mean the difference between hunger and a meal, or walking and public transport. Its marginal utility is enormous. For a billionaire, an additional dollar (or even a million dollars) adds very little to their overall well-being or quality of life. They can already afford anything they need or want. While total utility from money continues to increase, the marginal utility dramatically diminishes.

Why Does Diminishing Marginal Utility Matter?

This seemingly simple principle has far-reaching implications for individuals, businesses, and even governments.

1. For Consumers: Making Smarter Choices

- Optimal Consumption: DMU helps us understand that there’s an "optimal point" for consuming goods. We should consume up to the point where the marginal utility we get from the last unit is equal to its price (or what we have to give up for it). Beyond that, we’re essentially getting less value for our money.

- Avoiding Waste: Understanding DMU can help us avoid over-consuming or buying more than we truly need. Why buy a fifth similar shirt when the first two already provide ample utility and the fifth adds very little?

- Budgeting: It encourages us to diversify our spending. Instead of buying ten of the same item, it’s often more satisfying to buy one of ten different items, as each "first" unit provides higher marginal utility.

2. For Businesses: Pricing and Product Strategy

- Pricing Strategies: Companies often use DMU to inform their pricing. They might offer bulk discounts (e.g., "buy one, get one half off") because they know the marginal utility of the second item is lower for the consumer, so they need to offer a lower price to encourage the purchase.

- Product Development: Businesses understand that simply adding more features to a product doesn’t always increase its value proportionately. Beyond a certain point, extra features might even confuse users or add unnecessary cost, providing diminishing marginal utility.

- Marketing: Marketing often focuses on the initial excitement and high utility of a product, knowing that the "newness" factor provides significant satisfaction.

3. For Public Policy: Taxation and Welfare

- Progressive Taxation: Many tax systems are progressive, meaning higher earners pay a larger percentage of their income in taxes. This is partly justified by the concept of diminishing marginal utility of money. The argument is that taking an extra dollar from a very wealthy person causes less loss of utility than taking that same dollar from a very poor person.

- Welfare Programs: Providing basic necessities (food, shelter, healthcare) to those in need offers enormous marginal utility, significantly improving their well-being. The first units of these goods provide immense value.

Beyond Just "More": Finding Your Optimal Point

The law of diminishing marginal utility beautifully illustrates that more isn’t always better. True satisfaction often lies not in endless accumulation, but in finding the right balance.

- Quality Over Quantity: Instead of buying ten mediocre items, perhaps investing in one high-quality item that provides consistent, high utility is a more satisfying approach.

- Mindful Consumption: Understanding DMU encourages us to be more mindful of what we consume and why. Are we buying something because it genuinely adds value, or just out of habit or external pressure?

- Appreciation: It helps us appreciate the initial, high-utility experiences. The first cup of coffee in the morning, the first fresh apple, the first moment of quiet peace – these often provide the most profound satisfaction.

Conclusion: The Wisdom of Enough

The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility is more than just an economic concept; it’s a profound insight into human nature and the pursuit of happiness. It teaches us that our capacity for satisfaction from any single thing is finite. While total satisfaction can increase with more consumption, the joy derived from each additional unit inevitably wanes.

So, the next time you’re about to indulge in a second helping, buy another gadget you don’t really need, or chase an endless stream of wealth, remember the power of diminishing marginal utility. It’s a reminder that true fulfillment often comes not from always wanting more, but from appreciating what we have, understanding when "enough" is truly enough, and recognizing that the greatest utility often lies in variety, balance, and mindful living.

Post Comment