Credit Default Swaps: The Unseen Force Behind the 2008 Financial Crisis

The year 2008 stands as a stark reminder of the fragility of the global financial system. A crisis that began in the seemingly obscure world of subprime mortgages rapidly escalated, leading to bank failures, massive bailouts, and the deepest economic recession in generations. While many factors contributed to this catastrophe, one complex financial instrument played a particularly insidious role in amplifying the chaos: Credit Default Swaps (CDS).

Often described as the "financial weapons of mass destruction" by Warren Buffett, Credit Default Swaps were at the heart of the interconnected web of risk that brought the global economy to its knees. But what exactly are they, and how did they wield such devastating power? This article will demystify CDS, exploring their mechanics, their widespread use, and their catastrophic impact during the 2008 financial meltdown.

What Exactly is a Credit Default Swap (CDS)? Demystifying the "Insurance Policy"

To understand the impact of Credit Default Swaps, we first need to grasp what they are. At their core, a CDS can be thought of as a form of insurance policy against default.

Imagine this scenario:

- You (the "Protection Buyer") own a bond issued by Company X. You’re worried that Company X might default on its debt (i.e., not pay back the bondholders).

- You approach Bank Y (the "Protection Seller"). You pay Bank Y a regular fee (like an insurance premium) for a set period.

- The Agreement: In exchange for these fees, Bank Y agrees to compensate you if Company X defaults on its bond. If Company X does default, Bank Y pays you the face value of the bond, or a similar agreed-upon settlement. If Company X doesn’t default, Bank Y keeps your fees, and the contract expires.

Key Components of a CDS:

- Protection Buyer: The entity that pays premiums and receives a payout if a default occurs.

- Protection Seller: The entity that receives premiums and is obligated to pay out if a default occurs.

- Reference Entity: The specific bond issuer or loan that the CDS is based on (e.g., Company X in our example).

- Reference Obligation: The specific debt instrument (e.g., Company X’s bond).

- Credit Event: The trigger for payout, typically a bankruptcy, failure to pay, or restructuring.

The Crucial Distinction: You Don’t Need to Own the Underlying Asset!

Here’s where CDS depart significantly from traditional insurance and where their potential for systemic risk truly emerged. Unlike a car insurance policy where you must own the car to insure it, with a CDS, you don’t actually have to own the underlying bond or debt to buy protection on it.

This seemingly minor detail opened the door to widespread speculation. Investors could effectively "bet" on whether a company or a specific debt instrument would default, without ever having a direct stake in it. This meant that the total value of CDS contracts outstanding could far exceed the actual amount of the underlying debt they were supposedly "insuring."

The Pre-2008 Landscape: MBS, CDOs, and the "Wild West" of Finance

To understand how CDS became so dangerous, we need to look at the financial products they were often linked to, particularly in the lead-up to 2008:

- Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS): These were created by pooling thousands of individual home mortgages and then selling shares of that pool to investors. The investors would receive payments from the mortgage holders.

- Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs): CDOs took the concept of MBS a step further. They bundled together various debt instruments, including MBS (often the riskiest "tranches" or slices of MBS), corporate bonds, and other loans. These bundles were then sliced into different "tranches" based on perceived risk, with the riskiest tranches offering higher returns.

The Fatal Connection: CDS on MBS and CDOs

As the housing market boomed in the early 2000s, financial institutions created vast quantities of MBS and CDOs. Many of these contained subprime mortgages – loans made to borrowers with poor credit histories or insufficient income, who were highly likely to default.

Sophisticated investors, including banks, hedge funds, and insurance companies, began to buy and sell CDS on these MBS and CDOs.

- Banks and investors who owned MBS/CDOs bought CDS to "insure" their holdings against potential defaults by the underlying mortgage borrowers.

- Other investors, who didn’t necessarily own the MBS/CDOs, bought CDS as a speculative bet that these complex instruments would fail. They were effectively betting against the housing market.

The Unregulated and Opaque Market:

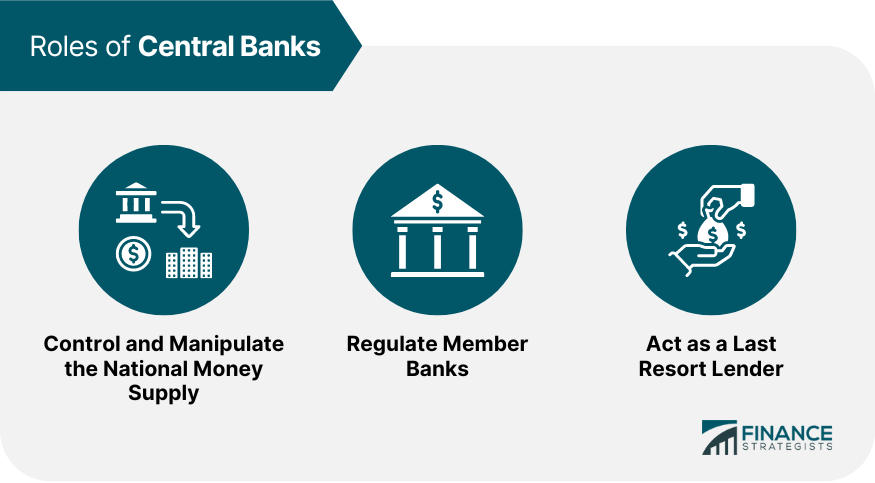

Crucially, the CDS market was largely unregulated and operated "over-the-counter" (OTC), meaning transactions happened directly between two parties without going through a centralized exchange. This led to:

- Lack of Transparency: No one had a clear picture of who owed what to whom.

- Massive Leverage: Institutions could take on enormous amounts of risk with relatively little capital.

- Counterparty Risk: If the protection seller (the "insurer") went bankrupt, the protection buyer was left with worthless insurance.

This environment was a ticking time bomb.

The Unraveling: How CDS Amplified the 2008 Crisis

The trigger for the 2008 crisis was the bursting of the U.S. housing bubble.

- Mortgage Defaults Skyrocket: As adjustable-rate mortgages reset and housing prices fell, millions of subprime borrowers began to default on their loans.

- MBS and CDO Values Plummet: With the underlying mortgages failing, the value of MBS and CDOs tied to these mortgages collapsed. What were once considered "safe" investments, particularly the higher-rated tranches, were suddenly worthless.

- CDS Protection Buyers Demand Payouts: As the value of MBS and CDOs evaporated, the "credit event" (default) occurred for countless reference entities. The protection buyers, who had paid their premiums, now demanded massive payouts from the protection sellers.

This is where the true power and danger of CDS became horrifyingly apparent.

Case Study 1: Lehman Brothers and Counterparty Risk

Investment bank Lehman Brothers was heavily involved in the MBS and CDO markets, both as an issuer and as a counterparty in countless CDS contracts. When the market crashed, Lehman found itself facing:

- Massive losses on its own holdings of MBS and CDOs.

- Enormous obligations as a protection seller on CDS contracts, as other institutions demanded payouts.

- Inability to collect on CDS contracts where they were the protection buyer, because their counterparties (other financial institutions) were also in distress or went bankrupt.

When Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008, it wasn’t just a bankruptcy; it sent shockwaves through the global financial system because of its vast network of CDS obligations. Other banks and institutions suddenly faced the terrifying prospect that the "insurance" they had bought from Lehman was now worthless, and they were left exposed to billions in losses. This counterparty risk created a terrifying domino effect.

Case Study 2: AIG and the "Too Big to Fail" Bailout

Perhaps no entity better exemplifies the catastrophic impact of CDS than the American International Group (AIG). AIG, a seemingly traditional insurance company, had a financial products division that had sold trillions of dollars in CDS protection, primarily on CDOs.

- Massive Exposure: AIG had guaranteed hundreds of billions of dollars worth of CDOs for banks around the world, essentially acting as the ultimate "insurer" against their default.

- No Collateral: In many cases, AIG did not have to post significant collateral for these guarantees when the market was booming, based on its AAA credit rating.

- The Calls for Collateral: When the underlying CDOs began to default, AIG’s credit rating plummeted. Under the terms of their CDS contracts, they were suddenly required to post billions in collateral to their counterparties (banks like Goldman Sachs, Société Générale, Deutsche Bank, and many others).

- Imminent Collapse: AIG simply did not have the cash to meet these collateral calls. Its collapse would have triggered a cascade of failures across the global financial system, as banks that had bought CDS protection from AIG would suddenly be exposed to trillions in losses.

This systemic threat led to the unprecedented $182 billion U.S. government bailout of AIG. It was not to save AIG itself, but to prevent the collapse of its counterparties and, by extension, the entire financial system. The bailout money essentially flowed through AIG to the banks that were its CDS counterparties.

The Aftermath: Lessons Learned and Regulatory Response

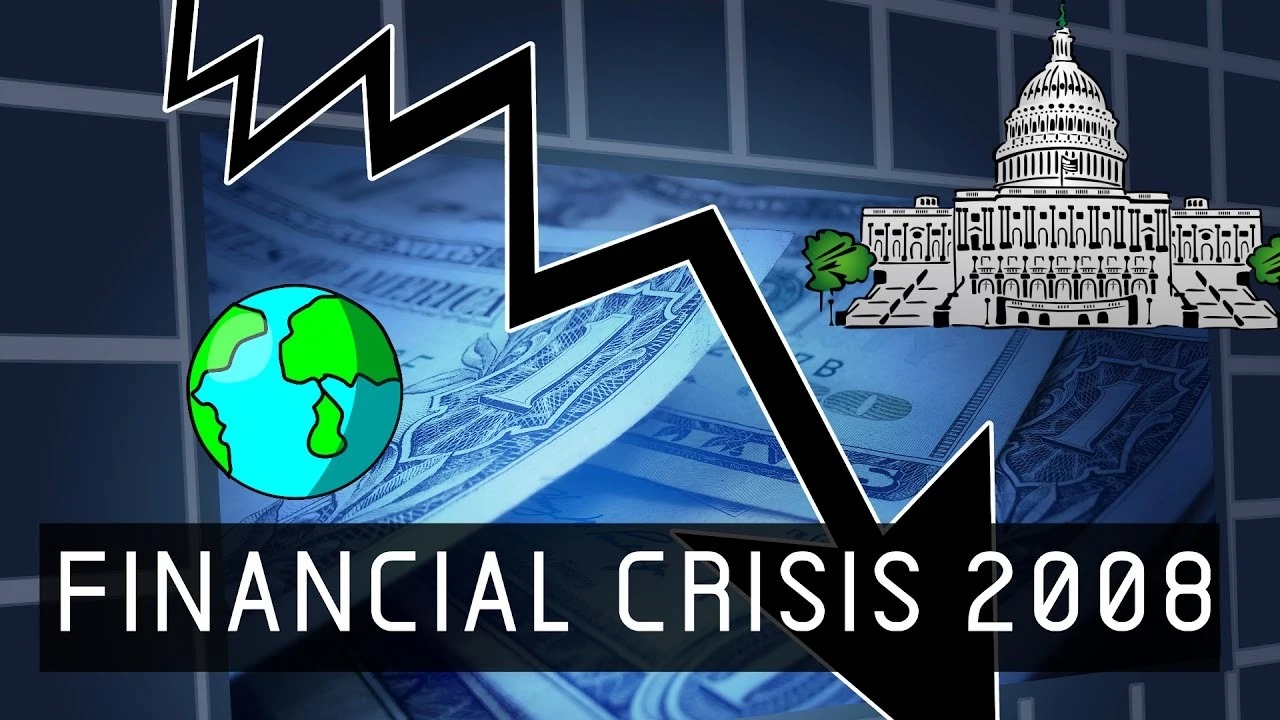

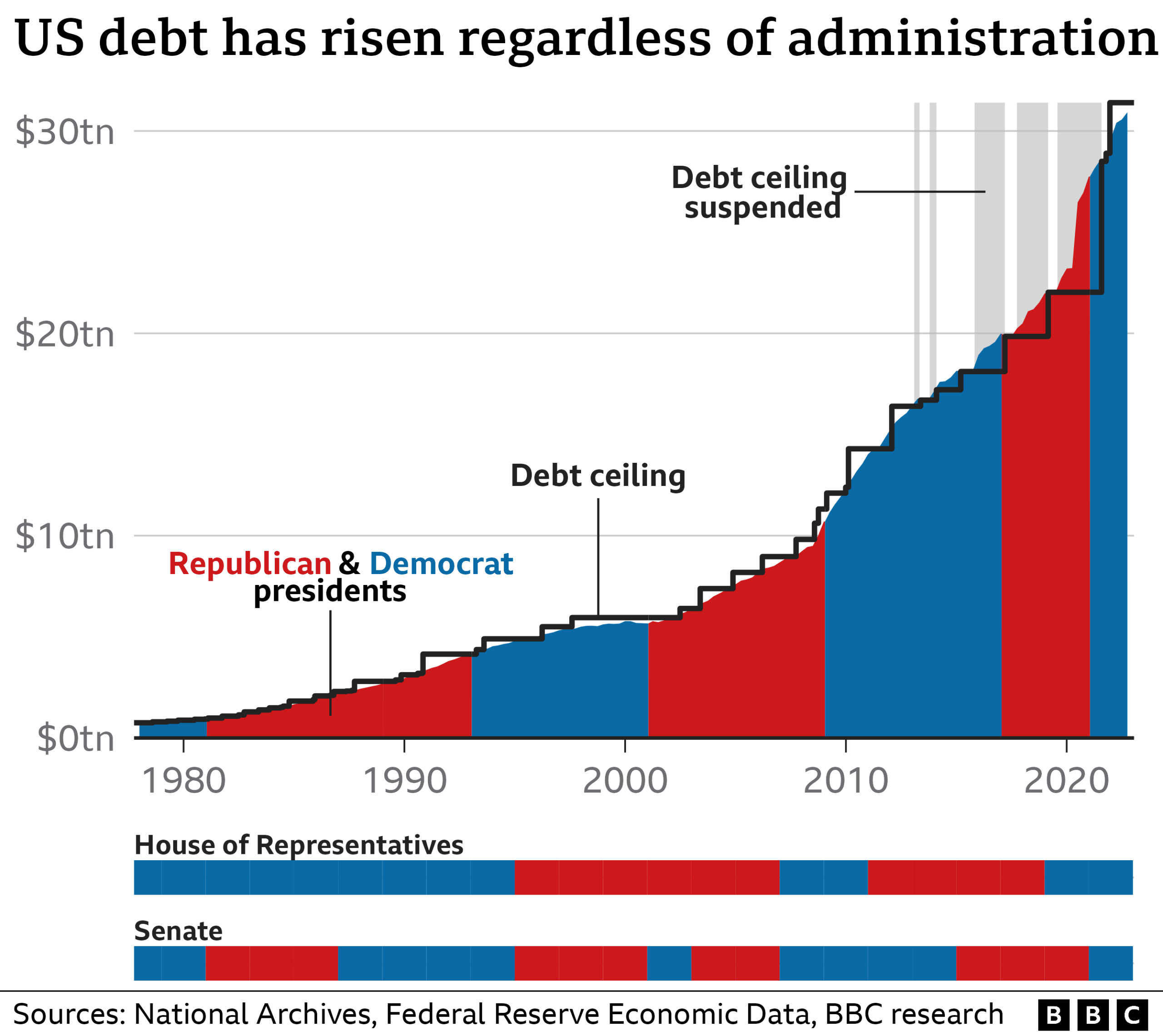

The 2008 crisis, heavily amplified by Credit Default Swaps, forced a painful reckoning with the dangers of an unregulated and opaque financial system. The immediate aftermath saw:

- A Freeze in Lending: Banks stopped lending to each other, fearing counterparty risk.

- Massive Government Interventions: Bailouts, quantitative easing, and stimulus packages became necessary to avert total collapse.

- Global Recession: Millions lost jobs, homes, and savings.

In response, governments and regulators around the world implemented significant reforms, most notably the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in the United States (2010). Key provisions aimed at regulating the derivatives market, including CDS, included:

- Central Clearing: Mandating that many standardized CDS contracts be cleared through central clearinghouses. This reduces counterparty risk by interposing a robust third party between buyers and sellers and ensuring that collateral is posted.

- Exchange Trading: Promoting the trading of standardized CDS on regulated exchanges to increase transparency and price discovery.

- Reporting Requirements: Requiring more data reporting on CDS transactions to regulators, providing greater oversight.

- Capital Requirements: Imposing stricter capital requirements on banks and financial institutions to ensure they have sufficient buffers against potential losses.

- The Volcker Rule: Aimed at limiting proprietary trading by banks (i.e., banks making speculative bets with their own money), including certain types of derivatives.

Conclusion: A Costly Lesson in Financial Innovation and Risk

Credit Default Swaps, initially conceived as a tool for managing risk, morphed into a powerful instrument for speculation and leverage that ultimately amplified one of the worst financial crises in history. Their unregulated nature, coupled with their widespread use in the opaque world of MBS and CDOs, created a dangerous web of interconnectedness that few understood and even fewer could control.

The 2008 crisis served as a profound and costly lesson about the perils of unchecked financial innovation and the critical importance of robust regulation. While reforms have been implemented to bring greater transparency and stability to the derivatives market, the memory of CDS’s impact in 2008 remains a powerful reminder of the potential for complex financial instruments to pose systemic risks to the global economy. Understanding their role is crucial for anyone seeking to comprehend the forces that shaped, and continue to shape, our financial world.

Post Comment