Balancing the Budget: Policy Choices, Economic Impact, and Future Consequences

Imagine your household budget. You have money coming in (your salary) and money going out (rent, groceries, bills). If you spend more than you earn, you go into debt. If you earn more than you spend, you save money.

A country’s government budget works in a very similar way, but on a much, much larger scale. It’s a fundamental aspect of a nation’s economic health, and how a government chooses to balance (or not balance) its budget has profound effects on every citizen, from the economy to social services, and even future generations.

This article will break down the complexities of balancing the budget, exploring the policy choices governments make, and the real-world consequences of those decisions.

Understanding the Government Budget: The Basics

Before we dive into balancing, let’s understand what a government budget actually is:

- Revenue (Income): This is the money the government collects. The vast majority comes from taxes.

- Income Tax: Paid by individuals on their earnings.

- Corporate Tax: Paid by businesses on their profits.

- Sales Tax: Added to the price of goods and services.

- Property Tax: Paid on real estate (often collected by local governments but contributes to overall public funds).

- Excise Taxes: Taxes on specific goods like tobacco, alcohol, or gasoline.

- Other Sources: Fees for government services, customs duties, earnings from state-owned enterprises, etc.

- Expenditure (Spending): This is how the government spends the money it collects. Government spending can be broadly categorized:

- Mandatory Spending: Programs where spending is automatically set by existing laws. This often includes major social safety nets.

- Social Security: Retirement and disability benefits.

- Medicare/Medicaid: Healthcare for the elderly, disabled, and low-income individuals.

- Interest on the National Debt: Payments made on money the government has borrowed in the past. This is a fixed cost that grows with the debt.

- Discretionary Spending: Funds that Congress (or the equivalent legislative body) decides each year during the annual appropriations process.

- Defense: Military spending, equipment, personnel.

- Education: Funding for schools, student aid, research.

- Infrastructure: Roads, bridges, public transport, utilities.

- Scientific Research: Funding for various scientific advancements.

- Environmental Protection: Agencies dedicated to preserving the environment.

- Foreign Aid: Assistance to other countries.

- Mandatory Spending: Programs where spending is automatically set by existing laws. This often includes major social safety nets.

Key Terms to Know:

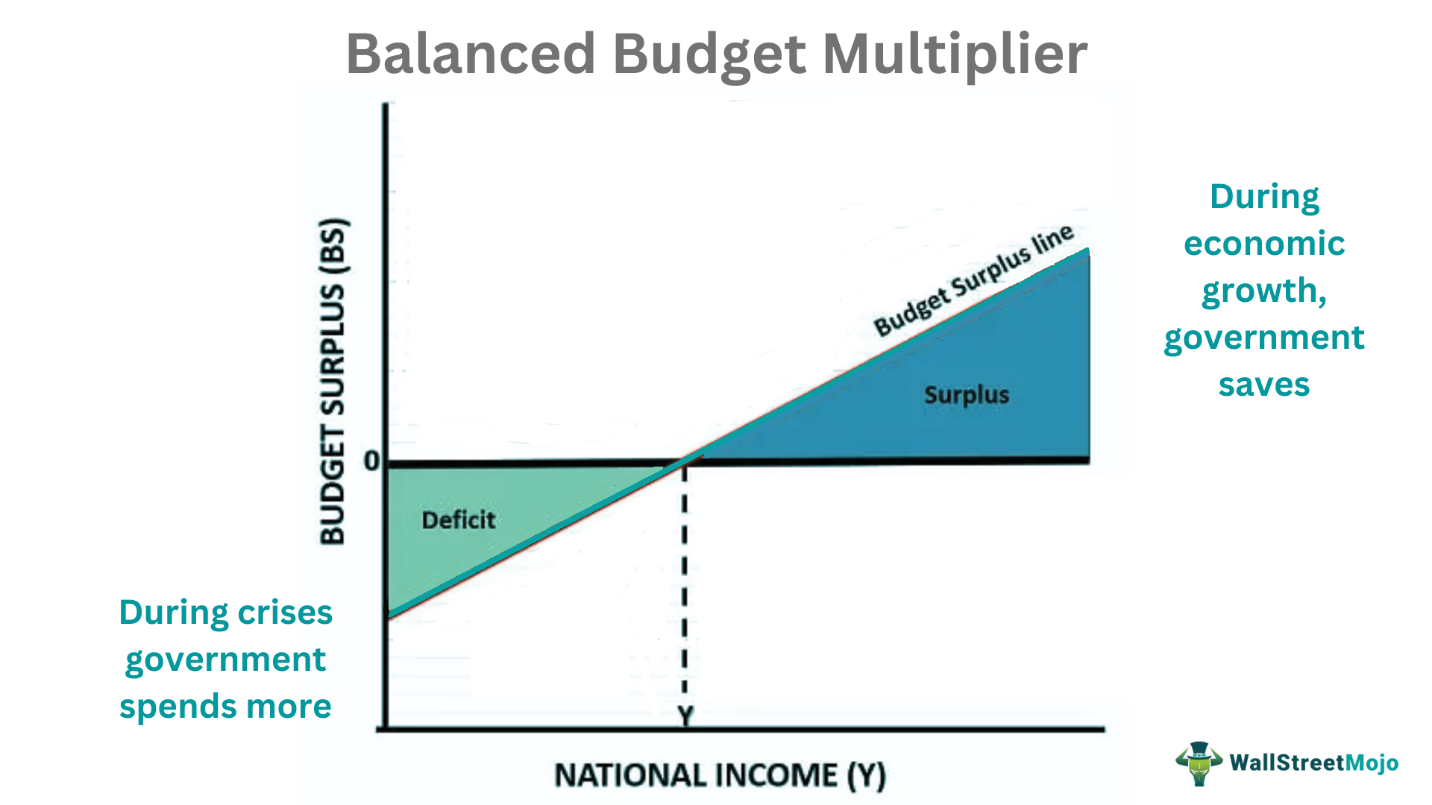

- Budget Deficit: Occurs when a government spends more money than it collects in a single year. This shortfall must be covered by borrowing.

- Budget Surplus: Occurs when a government collects more money than it spends in a single year. This extra money can be used to pay down debt, save, or fund new initiatives.

- National Debt: The total accumulation of all past budget deficits, minus any surpluses. It’s the total amount of money a government owes to its lenders (individuals, businesses, and other countries) over time.

Why Balance the Budget? The Importance of Fiscal Health

While it might seem abstract, a country’s budget balance has tangible effects on its present and future.

- Avoiding a Rising National Debt:

- Interest Payments: A larger debt means more money must be spent just to pay the interest, leaving less for essential services like education, healthcare, or infrastructure. It’s like having a huge credit card bill where most of your payment goes to interest, not the principal.

- Crowding Out: When the government borrows heavily, it competes with private businesses for available money. This can drive up interest rates, making it more expensive for businesses to borrow and invest, potentially slowing economic growth.

- Maintaining Economic Stability and Confidence:

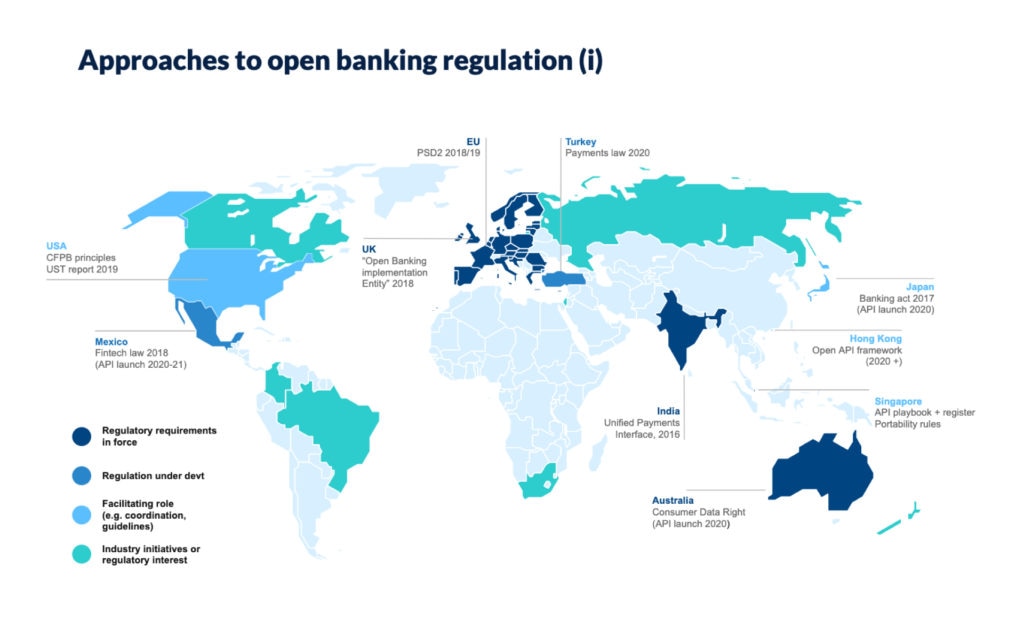

- Investor Confidence: Countries with uncontrolled debt can scare off investors, both domestic and international. If investors worry a country can’t repay its debts, they’ll demand higher interest rates or stop lending altogether.

- Credit Rating: Like individuals, countries have credit ratings. A lower rating means it costs more for the government to borrow, further increasing interest payments.

- Ensuring Future Flexibility:

- A high debt limits a government’s ability to respond to future crises (like recessions, pandemics, or natural disasters) because it has less room to borrow or stimulate the economy.

- It can also restrict investment in long-term growth areas like education and research.

- Intergenerational Equity: Unchecked borrowing can shift the burden of repayment to future generations, who will face higher taxes or reduced services.

Policy Choices: How Governments Balance the Budget

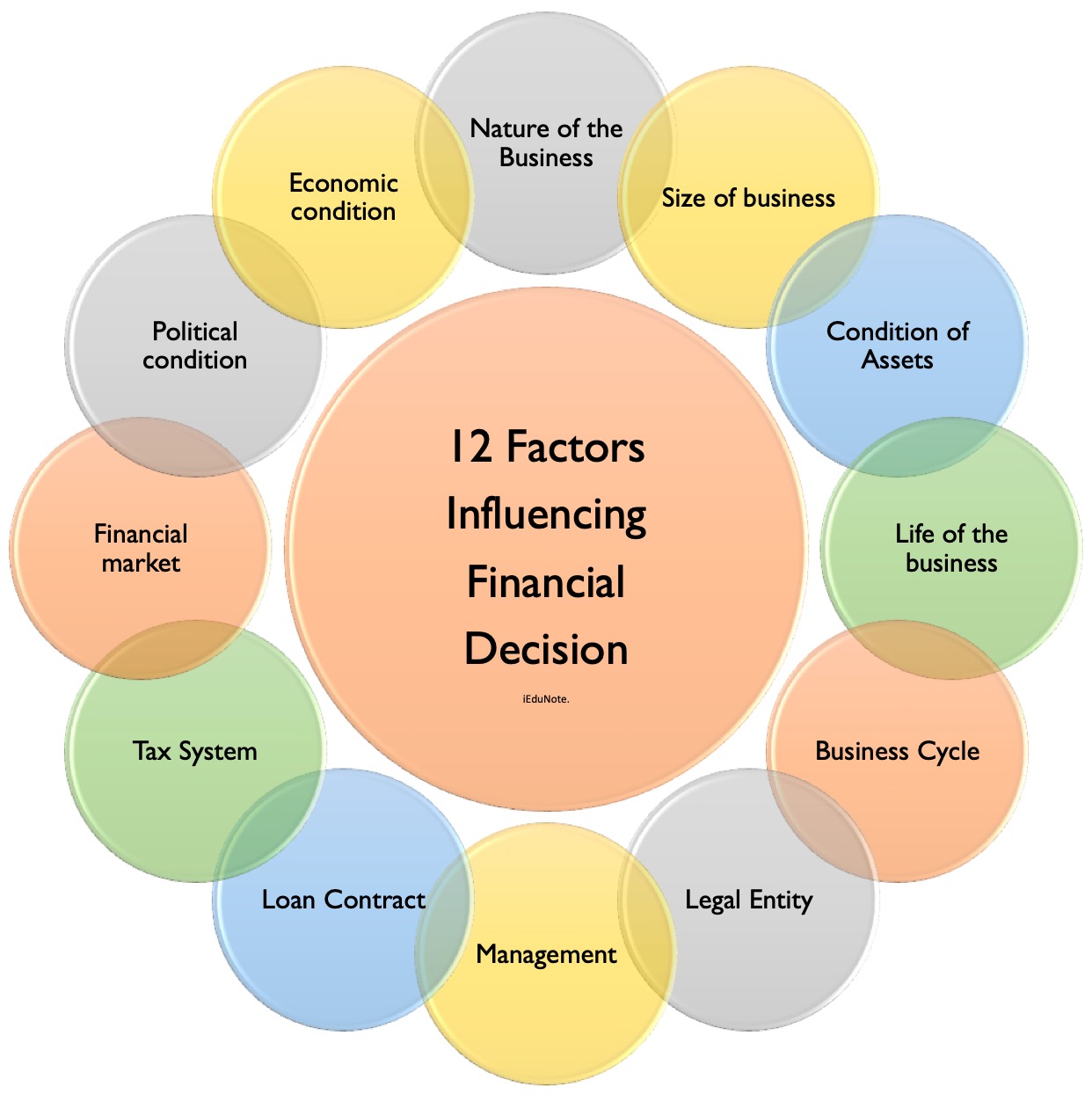

Governments have two main levers to pull when trying to balance the budget: increasing revenue or decreasing expenditure. Often, a combination of both is employed.

1. Increasing Revenue (The "Income" Side)

This primarily involves changes to the tax system.

- Raising Taxes:

- Pros: Can quickly increase government income, potentially funding needed programs or reducing debt.

- Cons: Can be unpopular, may reduce consumer spending (slowing the economy), and can disincentivize business investment if corporate taxes are too high. High income taxes might also prompt some skilled workers or businesses to leave the country.

- Examples: Increasing income tax rates, raising sales tax, adding new taxes (e.g., carbon tax).

- Broadening the Tax Base:

- Pros: Collects more revenue without necessarily raising existing tax rates, can make the tax system fairer by reducing loopholes.

- Cons: Can be politically difficult as it often involves eliminating tax breaks that benefit specific groups or industries.

- Examples: Closing tax loopholes, taxing previously untaxed goods or services.

- Promoting Economic Growth:

- Pros: This is often seen as the "best" way to increase revenue, as it naturally leads to more jobs, higher incomes, and greater corporate profits, all of which generate more tax revenue without raising tax rates.

- Cons: Economic growth is not entirely within the government’s direct control and can be influenced by global factors. Policies aimed at growth (like infrastructure investment) can take time to show results.

- Examples: Investing in education and infrastructure, fostering innovation, creating a stable business environment.

2. Decreasing Expenditure (The "Spending" Side)

This involves cutting back on government programs or services.

- Cutting Government Programs:

- Pros: Directly reduces spending, can free up funds for other priorities or debt reduction.

- Cons: Can be highly controversial and impact citizens directly. Cuts to social programs can hurt vulnerable populations. Cuts to defense or infrastructure might weaken national security or long-term economic potential.

- Examples: Reducing benefits for Social Security or Medicare, cutting funding for education, defense, or scientific research, reducing foreign aid.

- Reducing Waste and Inefficiency:

- Pros: Improves government efficiency, saves taxpayer money without cutting essential services. Generally popular with the public.

- Cons: While important, the total savings from waste reduction often represent a small fraction of the overall budget, making it difficult to significantly balance the budget through this method alone.

- Examples: Streamlining bureaucratic processes, auditing government agencies, negotiating better prices for government contracts.

Consequences of Budget Choices: The Ripple Effect

The choices governments make regarding revenue and expenditure have wide-ranging consequences, often creating a delicate balance between short-term pain and long-term gain (or vice versa).

1. Economic Consequences:

- Impact on GDP (Economic Growth):

- Austerity (Spending Cuts/Tax Hikes): Can slow economic growth in the short term as less money circulates in the economy. Businesses might reduce investment due to lower demand.

- Stimulus (Increased Spending/Tax Cuts): Can boost economic growth in the short term by increasing demand and encouraging investment. However, if not funded, it can increase the national debt.

- Inflation:

- Excessive spending (especially if financed by printing money) can lead to too much money chasing too few goods, causing prices to rise (inflation).

- Severe spending cuts can, in rare cases, lead to deflation (falling prices), which can also be harmful to the economy.

- Interest Rates:

- Large deficits requiring significant borrowing can push up interest rates, making it more expensive for everyone (businesses and individuals) to borrow money.

- Unemployment:

- Spending cuts can lead to job losses in government sectors or industries that rely on government contracts.

- Stimulus spending can create jobs, particularly in infrastructure or public works.

- Business Confidence:

- A clear, sustainable budget plan can increase business confidence, encouraging investment and hiring. Uncertainty or uncontrolled debt can have the opposite effect.

2. Social Consequences:

- Impact on Vulnerable Populations:

- Cuts to social safety nets (like unemployment benefits, food assistance, or housing subsidies) can disproportionately affect the poor, elderly, and disabled, increasing poverty and inequality.

- Access to Services:

- Reductions in funding for healthcare, education, or public transportation can lead to decreased quality or access to these essential services for all citizens.

- Income Inequality:

- Tax policies can either exacerbate or alleviate income inequality. Regressive taxes (like sales taxes, which take a larger percentage of income from the poor) can worsen it, while progressive taxes (like income taxes, which take more from higher earners) can help reduce it.

3. Long-Term Consequences:

- National Debt Burden:

- Persistent deficits lead to a growing national debt, increasing interest payments and potentially crowding out future investments.

- Credit Rating:

- A deteriorating fiscal situation can lead to a downgrade in a country’s credit rating, making future borrowing more expensive.

- Intergenerational Equity:

- Leaving a large national debt for future generations means they will either face higher taxes, fewer public services, or both, to pay for current consumption.

- Future Flexibility:

- A high debt limits a government’s ability to respond to future challenges or invest in long-term projects (like climate change adaptation or advanced research) without significant economic pain.

The Challenges and Trade-offs

Balancing the budget is rarely a simple math problem. It involves complex trade-offs, political considerations, and often, difficult choices.

- Political Difficulty: Cutting popular programs or raising taxes is almost always politically unpopular, making it challenging for elected officials to implement necessary changes, especially in the short term.

- Short-Term vs. Long-Term Thinking: Policies that might benefit the economy in the long run (like investing in education or infrastructure) might require short-term spending increases, while immediate budget cuts might have negative long-term consequences.

- Economic Conditions: Balancing the budget during a recession is very different from doing so during an economic boom. During a recession, governments often increase spending (stimulus) to support the economy, which can worsen deficits temporarily.

- Global Factors: A country’s budget is also affected by global economic conditions, international trade, and geopolitical events, which are beyond its direct control.

Conclusion: A Continuous Balancing Act

Balancing the budget is not a one-time event but a continuous process of policy choices and adjustments. It requires a clear understanding of economic principles, a willingness to make difficult decisions, and often, a public consensus on priorities.

For citizens, understanding these choices and their potential consequences is crucial. An informed populace can engage in more meaningful discussions about government spending, taxation, and the long-term fiscal health of their nation. While the numbers might seem daunting, at its heart, balancing the budget is about deciding what kind of future a country wants to build – and how it plans to pay for it.

Post Comment