Unlocking the Fundamentals: A Beginner’s Guide to Foundational Economic Concepts

Have you ever wondered why some things are expensive while others are cheap? Why governments make certain decisions about spending, or why companies choose to produce specific goods? The answers to these questions lie in the fascinating world of economics. Far from being a dry, complicated subject, economics is all about understanding how people, businesses, and governments make choices when faced with limitations.

This comprehensive guide will demystify the foundational economic concepts that underpin our world. Whether you’re a student, an aspiring entrepreneur, or simply curious about how the economy works, understanding these core principles is your first step towards making more informed decisions in your personal and professional life.

I. The Pillars of Economic Thought: Scarcity, Choice, and Opportunity Cost

At the very heart of all economic thinking lies a fundamental problem: we have unlimited wants but limited resources. This simple truth gives rise to the most crucial concepts in economics.

1. Scarcity: The Core Problem

- Definition: Scarcity is the basic economic problem of having seemingly unlimited human wants and needs in a world of limited resources. It’s not about poverty; even the wealthiest individuals and nations face scarcity.

- Why it Matters: Because resources (time, money, natural resources, labor, technology) are finite, we can’t have everything we want. This forces us to make choices.

- Examples:

- Time: You have only 24 hours in a day. You can’t study for an exam, work a full shift, and binge-watch a new series all at the same time.

- Money: Your monthly income is limited. You can’t buy every gadget, take every trip, and eat out every night.

- Natural Resources: Oil, clean water, and fertile land are finite resources.

2. Choice: The Inevitable Consequence of Scarcity

- Definition: Since resources are scarce, every individual, business, and government must make choices about how to allocate them. Every decision we make involves choosing one thing over another.

- The "What, How, and For Whom" Questions: Societies must answer three basic economic questions:

- What to produce? (e.g., more cars or more public transportation?)

- How to produce? (e.g., using more labor or more machinery?)

- For whom to produce? (e.g., who gets the goods and services?)

3. Opportunity Cost: The True Cost of Every Decision

- Definition: Opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative that you give up when you make a choice. It’s not just the monetary cost, but the real cost in terms of what you forgo.

- Why it’s Important: Understanding opportunity cost helps us make better, more rational decisions by considering the trade-offs involved.

- Examples:

- Going to College: The opportunity cost isn’t just tuition and books; it’s also the income you could have earned if you had worked full-time instead.

- Government Spending: If a government decides to build a new highway, the opportunity cost might be a new hospital or improved schools that could have been built with the same funds.

- Leisure Time: Choosing to spend an evening watching TV means giving up the opportunity to exercise, read a book, or socialize.

II. How Decisions Are Made: Rationality, Incentives, and Marginal Thinking

Economics assumes that people behave in predictable ways, driven by their self-interest and in response to various factors.

4. Rationality and Incentives: Driving Human Behavior

- Rationality (or Rational Self-Interest): In economics, "rational" means that individuals make choices that they believe will maximize their satisfaction or achieve their goals, given the information available to them. It doesn’t mean perfect knowledge, but rather purposeful behavior.

- Incentives: These are factors that motivate individuals and firms to act in a certain way. They can be positive (rewards) or negative (penalties).

- Examples:

- Positive Incentive: A bonus for exceeding sales targets encourages employees to work harder.

- Negative Incentive: A tax on sugary drinks might discourage consumption.

- Rational Choice: A student studies harder for an exam because they are incentivized by the desire for a good grade and future career prospects.

5. Marginal Thinking: Decisions at the Edge

- Definition: Marginal thinking involves making decisions by considering the additional (or "marginal") benefits and costs of one more unit of an activity. It’s about thinking in small, incremental steps, rather than all-or-nothing choices.

- Why it’s Useful: Most decisions in life aren’t "all or nothing" but rather "a little more" or "a little less."

- Examples:

- Studying: You don’t decide whether to study for 0 or 10 hours; you decide whether to study for one more hour. What’s the marginal benefit (better grade) versus the marginal cost (lost sleep or leisure)?

- Production: A company decides whether to produce one more unit of a product. Does the additional revenue from selling that unit outweigh the additional cost of producing it?

III. Understanding Markets and Production: Supply, Demand, and Efficiency

Markets are the primary mechanism through which resources are allocated in most modern economies. Understanding how they work is fundamental.

6. Economic Systems: Organizing Society’s Choices

Different societies organize themselves in different ways to answer the basic economic questions (What, How, For Whom).

- Traditional Economy: Decisions are based on customs, traditions, and beliefs, often passed down through generations. (e.g., some indigenous communities).

- Command Economy (or Planned Economy): A central authority (like the government) makes all major economic decisions. (e.g., Cuba, North Korea).

- Market Economy (or Free Market/Capitalism): Decisions are made by individuals and businesses interacting in markets, driven by supply and demand, with minimal government intervention. (e.g., largely theoretical, closest are countries like Hong Kong).

- Mixed Economy: A combination of market and command elements, where most decisions are made by individuals and businesses, but the government plays a significant role in regulating and providing public services. (Most countries today, including the USA, Canada, UK).

7. Supply and Demand: The Invisible Hand of the Market

Supply and demand are the forces that determine prices and quantities in a market economy.

-

Demand:

- Definition: The quantity of a good or service that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a specific period.

- Law of Demand: As the price of a good increases, the quantity demanded decreases (and vice-versa), assuming all other factors remain constant. This is why demand curves slope downward.

- Factors Affecting Demand (beyond price): Income, tastes/preferences, price of related goods (substitutes/complements), expectations, number of buyers.

-

Supply:

- Definition: The quantity of a good or service that producers are willing and able to offer for sale at various prices during a specific period.

- Law of Supply: As the price of a good increases, the quantity supplied increases (and vice-versa), assuming all other factors remain constant. This is why supply curves slope upward.

- Factors Affecting Supply (beyond price): Input costs, technology, number of sellers, expectations, government policies (taxes/subsidies).

-

Market Equilibrium:

- Definition: The point where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. At this price (equilibrium price), there is no shortage or surplus, and the market "clears."

- Surplus: When supply exceeds demand (price is too high).

- Shortage: When demand exceeds supply (price is too low).

- Market Self-Correction: Markets naturally tend towards equilibrium through price adjustments.

8. Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF): Visualizing Trade-offs

- Definition: A graphical representation showing the maximum possible output combinations of two goods or services that an economy can produce, given its available resources and technology, assuming full efficiency.

- What it Illustrates:

- Scarcity: Points outside the curve are unattainable with current resources.

- Choice: Moving along the curve involves choosing different combinations.

- Opportunity Cost: The downward slope of the curve shows the trade-off. To produce more of one good, you must give up some of the other.

- Efficiency: Points on the curve represent efficient production (no wasted resources).

- Inefficiency: Points inside the curve indicate underutilization of resources.

- Economic Growth: An outward shift of the PPF represents economic growth (more resources or better technology).

IV. Broader Perspectives and Real-World Applications

Economics is broadly divided into two main branches, each focusing on different levels of analysis.

9. Microeconomics vs. Macroeconomics: Zooming In and Out

-

Microeconomics:

- Focus: The study of how individual households, firms, and industries make decisions and interact in markets.

- Questions Addressed: How does a price change affect consumer behavior? What factors determine a firm’s production decisions? How do wages impact employment in a specific industry?

- Topics: Consumer behavior, firm production, market structures (competition, monopoly), labor markets, specific industry analysis.

-

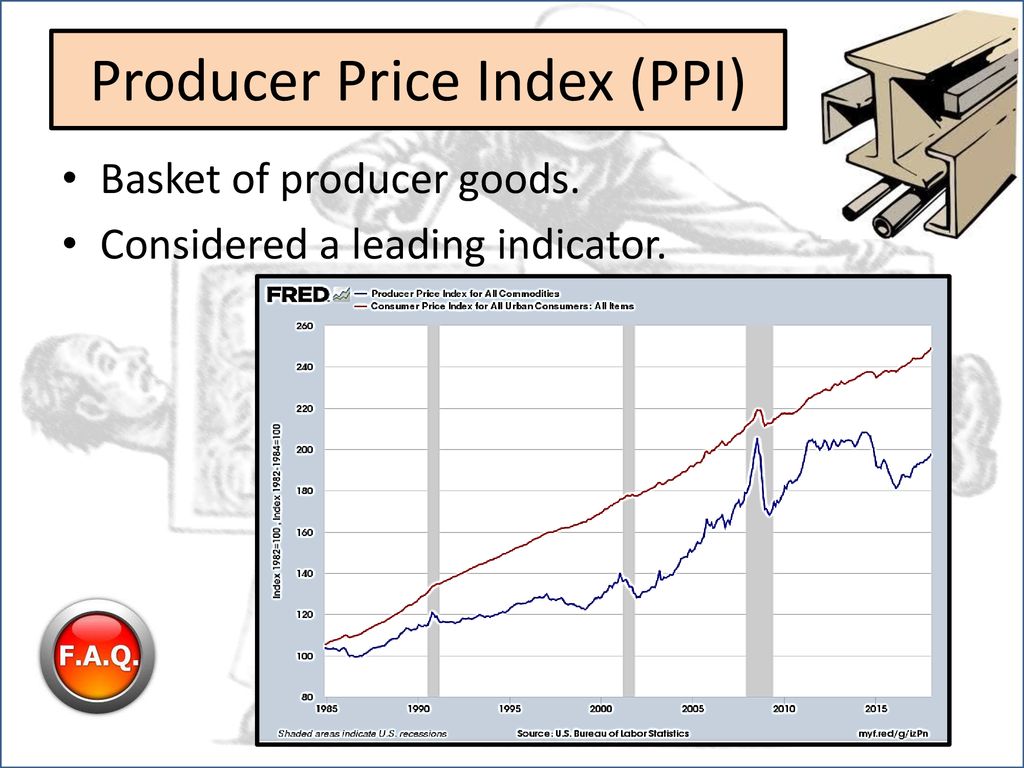

Macroeconomics:

- Focus: The study of the economy as a whole, looking at aggregate phenomena.

- Questions Addressed: What causes inflation? What are the factors that lead to economic growth or recession? How does government policy affect unemployment?

- Topics: Gross Domestic Product (GDP), inflation, unemployment, national income, monetary policy, fiscal policy, international trade balances.

10. Efficiency vs. Equity: The Balancing Act

-

Efficiency:

- Definition: Maximizing the output from available resources; getting the most out of what you have. In economics, this often refers to allocative efficiency (resources are allocated to produce the goods and services that society values most) and productive efficiency (goods are produced at the lowest possible cost).

- Example: A factory operating at full capacity with minimal waste is efficient.

-

Equity (or Equality):

- Definition: Refers to the fairness of the distribution of economic prosperity among the members of society. This is a normative concept, meaning it involves value judgments.

- Example: Debates about progressive taxation, social welfare programs, or minimum wage laws often revolve around equity concerns.

-

The Trade-off: There is often a trade-off between efficiency and equity. Policies designed to promote greater equality (e.g., high taxes on the wealthy) might reduce incentives for productivity and efficiency, while policies focused purely on efficiency might lead to greater income inequality.

11. Specialization and Trade: The Benefits of Cooperation

- Specialization:

- Definition: When individuals, firms, or countries focus on producing a limited range of goods or services in which they have a comparative advantage (can produce at a lower opportunity cost).

- Benefits: Leads to increased productivity and efficiency because people become experts at what they do.

- Trade:

- Definition: The voluntary exchange of goods and services.

- Benefits of Trade:

- Increased Variety: Consumers have access to a wider range of goods.

- Lower Costs: Goods can be produced where they are cheapest and then traded.

- Higher Standard of Living: By specializing and trading, countries can consume beyond their own production possibilities.

- Comparative Advantage: The fundamental reason for trade; countries benefit by specializing in and exporting goods they can produce at a lower opportunity cost, and importing goods that others can produce at a lower opportunity cost.

12. Market Failures and the Role of Government

While markets are powerful engines for allocating resources, they don’t always work perfectly. When they fail, there’s often a role for government intervention.

-

Market Failure:

- Definition: Situations where the free market fails to allocate resources efficiently, leading to a suboptimal outcome for society.

- Common Causes:

- Externalities: Costs or benefits imposed on a third party not directly involved in the transaction.

- Negative Externality: Pollution from a factory affects nearby residents.

- Positive Externality: Education benefits not just the student, but society as a whole (more informed citizens).

- Public Goods: Goods that are non-rival (one person’s consumption doesn’t diminish another’s) and non-excludable (difficult to prevent people from consuming them even if they don’t pay).

- Examples: National defense, street lights, clean air. Markets typically under-provide public goods because of the "free-rider problem."

- Imperfect Information: When one party in a transaction has more or better information than the other, leading to inefficient outcomes. (e.g., buying a used car).

- Monopolies/Market Power: When a single firm or a small group of firms dominates a market, they can restrict output and charge higher prices than in a competitive market, leading to inefficiency.

- Externalities: Costs or benefits imposed on a third party not directly involved in the transaction.

-

Role of Government:

- Correcting Market Failures:

- Externalities: Taxes on negative externalities (e.g., carbon tax), subsidies for positive externalities (e.g., research grants).

- Public Goods: Direct provision (e.g., military, roads).

- Imperfect Information: Regulations (e.g., food labeling, financial disclosure).

- Monopolies: Antitrust laws, regulation of natural monopolies.

- Providing a Legal and Social Framework: Enforcing property rights, contracts, and a stable legal system necessary for markets to function.

- Redistribution of Income: Through taxes and welfare programs to address equity concerns.

- Stabilizing the Economy: Using fiscal (government spending/taxes) and monetary (interest rates/money supply) policies to manage inflation, unemployment, and economic growth.

- Correcting Market Failures:

Conclusion: Economics is Everywhere

These foundational economic concepts are not abstract theories confined to textbooks. They are the very principles that govern our daily lives, from the choices we make about what to buy, to the policies our governments implement, and the global interactions between nations.

By understanding scarcity, choice, opportunity cost, the dynamics of supply and demand, and the broader interplay of micro and macroeconomic forces, you gain a powerful lens through which to view the world. You’ll begin to recognize the hidden economic drivers behind news headlines, business strategies, and even your own personal decisions.

This journey into foundational economics is just the beginning. The more you explore, the more you’ll appreciate the intricate and often surprising ways in which our economic world operates. So, keep asking questions, keep observing, and keep thinking like an economist!

Post Comment