Government Debt: When Does It Become a Crisis? A Beginner’s Guide

Government debt can sound like a scary, complex topic, but it’s a fundamental part of how modern economies work. Just like individuals or businesses, governments often borrow money to fund their activities. The real question isn’t if they borrow, but how much and when does that borrowing become a serious problem – a crisis?

This article will break down government debt in simple terms, explore why governments borrow, identify the warning signs that debt is becoming dangerous, and explain what happens when a country faces a debt crisis.

What Exactly Is Government Debt? (The Basics)

Imagine your household budget. Sometimes, your expenses (bills, groceries, rent) are more than your income (salary). To cover the difference, you might put it on a credit card or take out a loan.

Government debt works in a very similar way:

- Income: This comes primarily from taxes (income tax, sales tax, corporate tax, etc.) and other fees.

- Expenses: This includes everything a government spends money on: healthcare, education, defense, infrastructure (roads, bridges), social security, salaries for public workers, and much more.

- Budget Deficit: If a government spends more than it collects in taxes in a given year, it has a budget deficit.

- Government Debt (or National Debt/Public Debt): To cover that deficit, the government borrows money. The accumulation of all past deficits (minus any surpluses) is the total government debt.

Who do governments borrow from? Mostly from investors (both domestic and international) who buy "government bonds" or "treasury bills." These are essentially "IOUs" where the government promises to pay back the borrowed money with interest after a certain period.

Why Do Governments Borrow Money? (It’s Not Always Bad!)

Borrowing isn’t inherently bad. In fact, it’s often a necessary and even beneficial tool for a country’s development and stability. Here are the main reasons governments take on debt:

-

Funding Essential Public Services:

- Healthcare: Building hospitals, funding medical research, covering health insurance.

- Education: Schools, universities, teacher salaries.

- Infrastructure: Roads, bridges, airports, public transport, internet networks. These are long-term investments that boost economic growth.

-

Responding to Crises and Emergencies:

- Recessions: During economic downturns, tax revenues fall, and governments often increase spending (e.g., unemployment benefits, stimulus packages) to prevent a deeper collapse.

- Wars: Military spending can skyrocket during conflicts.

- Natural Disasters: Rebuilding after hurricanes, earthquakes, or floods.

- Pandemics: Funding vaccines, emergency relief, supporting businesses and individuals (e.g., the COVID-19 response).

-

Smoothing the Economy (Stimulus):

- When the economy is slow, governments can borrow and spend to create jobs and boost demand, helping the economy recover. This is often called "fiscal stimulus."

-

Managing Short-Term Cash Flow:

- Just like a business, a government’s tax income doesn’t always perfectly align with its spending needs throughout the year. Borrowing helps manage these gaps.

-

Investing for Future Generations:

- Large infrastructure projects or research initiatives can benefit a country for decades. Borrowing allows current generations to pay some, but future generations who also benefit contribute to the cost.

When Does Government Debt Become a Problem? (Warning Signs)

While borrowing is normal, too much debt, or debt that grows too quickly, can become a serious problem. Here are the key warning signs that a country’s debt might be heading towards a crisis:

-

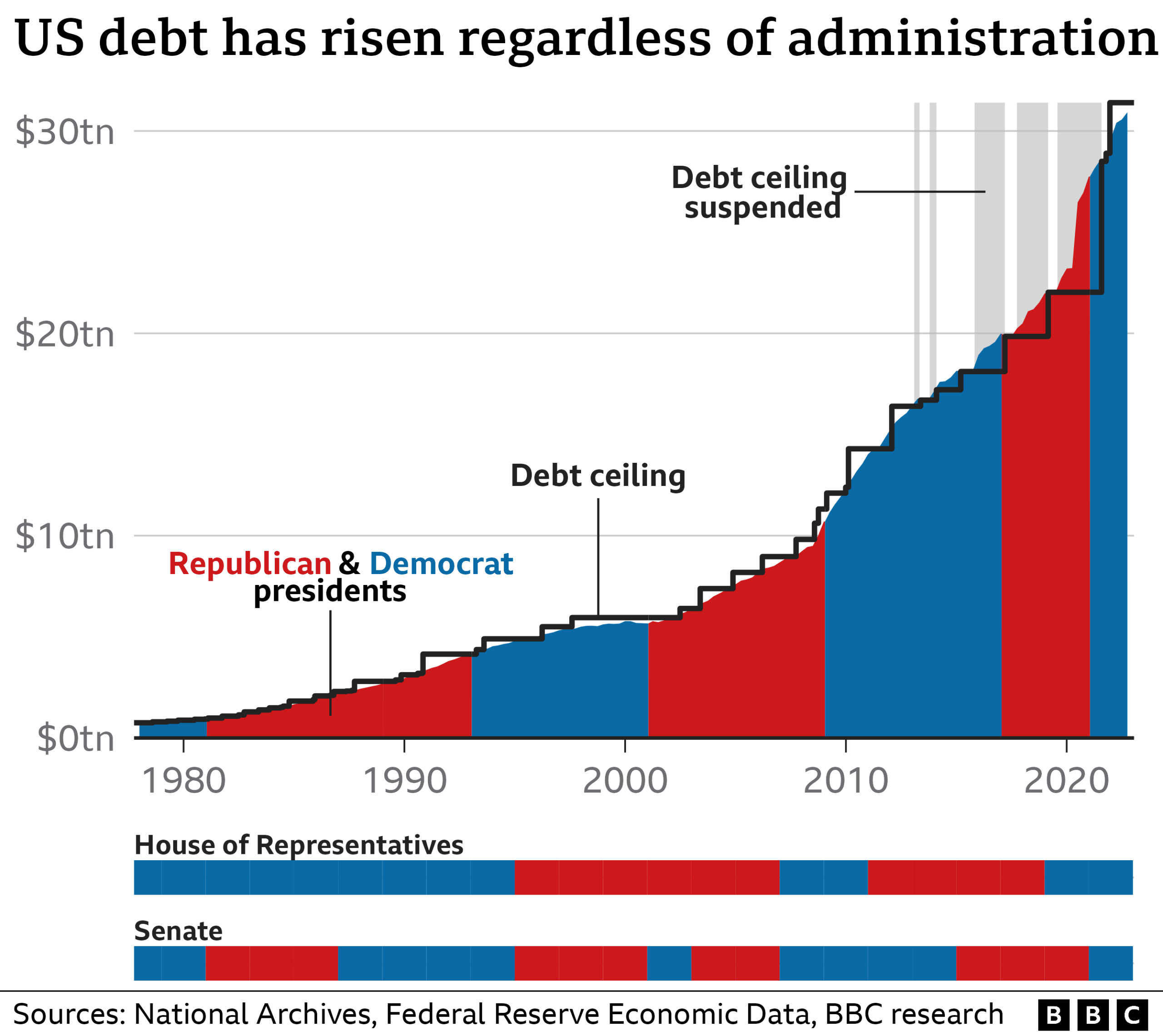

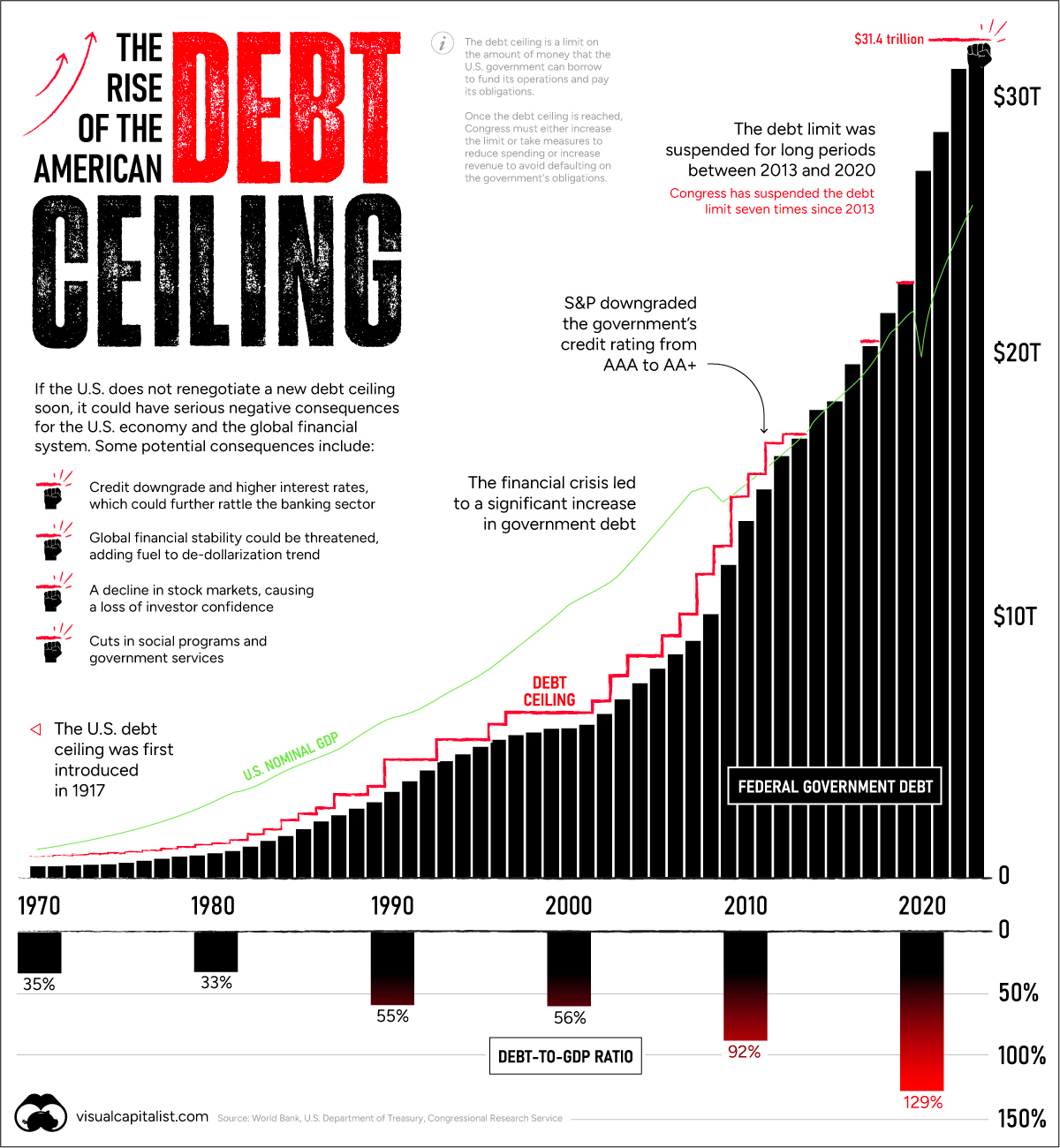

High Debt-to-GDP Ratio:

- What it is: This is the most common metric. It compares a country’s total government debt to its total economic output (Gross Domestic Product, or GDP) for a year. Think of it like comparing your total debt to your annual salary.

- Why it matters: A high ratio means the country’s debt is large relative to its ability to pay it back. There’s no magic number, but when this ratio gets very high (e.g., above 100-120% for developed nations, or much lower for developing ones), it can signal trouble.

- Example: If a country has a GDP of $1 trillion and a debt of $1.2 trillion, its debt-to-GDP ratio is 120%.

-

Rapidly Rising Interest Payments:

- What it is: Like any loan, governments have to pay interest on their debt.

- Why it matters: If the debt grows, or if interest rates rise, a larger portion of the government’s budget has to go towards paying interest, leaving less money for essential services like healthcare, education, or infrastructure. This can create a vicious cycle where borrowing more just covers interest.

-

Loss of Investor Confidence (and Higher Borrowing Costs):

- What it is: When investors (who buy government bonds) start to worry that a country might not be able to pay back its debt, they become less willing to lend money.

- Why it matters: To entice investors, the government has to offer higher interest rates on its new bonds. This makes borrowing even more expensive, worsening the debt problem and making it harder to fund future needs. A country’s "credit rating" (like a personal credit score) can be downgraded, further signaling risk.

-

Currency Devaluation:

- What it is: If investors lose faith in a country’s economy due to high debt, they might sell off that country’s currency. This causes the currency’s value to drop compared to other currencies.

- Why it matters:

- Imports become more expensive: This can lead to higher prices for everyday goods if the country relies on imports.

- Inflation: Rising import prices can contribute to general price increases (inflation) across the economy.

- Loss of purchasing power: Citizens’ money buys less internationally.

-

Inability to Borrow or "Rollover" Debt:

- What it is: Governments constantly issue new debt to pay off old debt as it matures (this is called "rolling over" debt).

- Why it matters: If investors refuse to buy new bonds, or demand impossibly high interest rates, the government can’t repay its old debt. This is a critical point that can quickly lead to a crisis.

The "Crisis Point": What Happens Then?

When the warning signs are ignored or spiral out of control, a country can hit a full-blown debt crisis. The consequences can be severe:

-

Default:

- What it is: This is when a government simply cannot (or will not) pay back its debts. It’s like a person declaring bankruptcy.

- Consequences: Default is devastating. It destroys a country’s reputation in financial markets, making it almost impossible to borrow again for a long time, except at extremely high interest rates. It can lead to:

- Bank runs: People lose faith in banks holding government debt.

- Economic collapse: Businesses can’t get loans, foreign investment flees, and the economy grinds to a halt.

- International isolation: Other countries may be wary of trading or dealing with a defaulting nation.

-

Austerity Measures:

- What it is: Even if a government avoids outright default, it might be forced to undertake drastic measures to reduce its debt. This often involves severe spending cuts and/or tax increases.

- Consequences: While necessary to restore financial health, austerity can be very painful in the short term:

- Reduced public services: Cuts to healthcare, education, social welfare.

- Job losses: In the public sector and in industries reliant on government spending.

- Economic recession: Austerity can further slow down an already struggling economy, leading to higher unemployment and lower living standards.

- Social unrest: Citizens often protest against cuts that affect their daily lives.

Real-World Examples:

- Greece (2010s): Faced a severe debt crisis after years of high spending and insufficient tax collection. It required massive bailout packages from the Eurozone and IMF, coupled with harsh austerity, to avoid default and stay in the Euro.

- Argentina (multiple times): Has defaulted on its debt several times throughout its history, leading to currency crashes, high inflation, and deep recessions.

Is All High Debt Bad? (The Nuance)

It’s important to remember that a high debt-to-GDP ratio alone doesn’t always mean a crisis is imminent. Context matters:

- Developed vs. Developing Nations: Richer countries (like Japan or the US) can often sustain higher debt levels because their economies are stable, they can borrow in their own currency, and they have strong institutions. Developing nations are much more vulnerable.

- Purpose of Debt: Debt taken on for productive investments (like infrastructure or education) that boost future economic growth is generally more sustainable than debt used just to fund current consumption or inefficient spending.

- Interest Rates: If a government can borrow at very low interest rates, even a large debt can be manageable. If rates spike, the situation can quickly become unsustainable.

- Economic Growth: A growing economy helps manage debt. As GDP increases, the debt-to-GDP ratio naturally improves, and the government’s ability to collect taxes (and thus pay down debt) increases.

Managing Government Debt: What Can Be Done?

Governments have several tools to manage and reduce their debt:

-

Fiscal Discipline:

- Spending Cuts: Reducing government expenditures in various areas.

- Tax Increases: Raising taxes to increase revenue.

- Budget Surpluses: Aiming to collect more in taxes than is spent, which can then be used to pay down debt.

-

Economic Growth:

- Policies that stimulate economic activity (e.g., investment in R&D, business-friendly regulations) increase GDP and tax revenues, making debt easier to manage.

-

Debt Restructuring:

- Negotiating with creditors to change the terms of the debt, such as extending repayment periods or reducing the interest rate. This can avoid default but often involves difficult negotiations.

-

Monetary Policy:

- Central banks (like the Federal Reserve in the US) can influence interest rates. Lower rates make it cheaper for governments to borrow, but very low rates for too long can lead to inflation.

The Bottom Line for Citizens

Government debt might seem like an abstract concept, but it directly affects your life:

- Your Taxes: If debt needs to be reduced, it often means higher taxes or cuts to services you rely on.

- Public Services: Less money for schools, hospitals, roads, and other essential services.

- Economic Stability: A debt crisis can lead to job losses, currency devaluation, and a general decline in living standards.

- Future Generations: High debt passed on means future taxpayers will bear the burden of repayment or face reduced public services.

Understanding government debt empowers you to be a more informed citizen and to hold your elected officials accountable for responsible fiscal management. It’s a delicate balancing act – borrowing to invest and respond to crises is necessary, but allowing debt to spiral out of control can lead to severe economic pain. The crisis point is reached when a government can no longer service its debt without causing severe harm to its economy or resorting to default.

Post Comment