Unlocking True Worth: A Beginner’s Guide to Company Valuation Methods and Techniques

Ever wondered how companies like Google, Apple, or even your local bakery get their "price tag"? It’s not magic, but a careful blend of art and science known as company valuation. Whether you’re an aspiring investor, a budding entrepreneur, or simply curious about the business world, understanding how companies are valued is a fundamental skill.

This comprehensive guide will demystify the world of company valuation, breaking down complex concepts into easy-to-understand language. We’ll explore why valuation matters, the core methods used, and the techniques financial experts employ to estimate a company’s true worth.

What Exactly is Company Valuation?

At its core, company valuation is the process of determining the economic value of a whole business or company unit. Think of it like trying to figure out how much a house is worth before you buy or sell it. You wouldn’t just guess, right? You’d look at its features, its condition, what similar houses in the area sold for, and what kind of rental income it could generate.

Similarly, valuing a company involves analyzing various factors, including its assets, earnings, market conditions, and future potential, to arrive at a reasonable estimated value.

Why is Company Valuation Crucial?

Valuation isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s a critical tool used in a multitude of real-world scenarios. Here are some of the most common reasons why companies are valued:

- Investment Decisions: For investors, valuation helps determine if a company’s stock is undervalued (a good buy) or overvalued (a risky buy). It’s key to making informed choices.

- Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A): When one company wants to buy another, valuation helps the buyer determine a fair purchase price and the seller understand what their business is truly worth.

- Fundraising (for Startups & Growth Companies): Startups seeking capital from venture capitalists or angel investors need a clear valuation to determine how much equity (ownership) to give up for a given investment.

- Selling a Business: If you’re looking to sell your business, a professional valuation gives you a strong basis for negotiation and helps you set a realistic asking price.

- Strategic Planning: Companies use internal valuations to understand their own performance, identify areas for improvement, and make strategic decisions about future growth, divestitures, or resource allocation.

- Legal & Tax Purposes: Valuations are often required for legal disputes, estate planning, divorce settlements, and tax reporting.

- Initial Public Offerings (IPOs): Before a company goes public, investment banks perform extensive valuations to set the initial stock price.

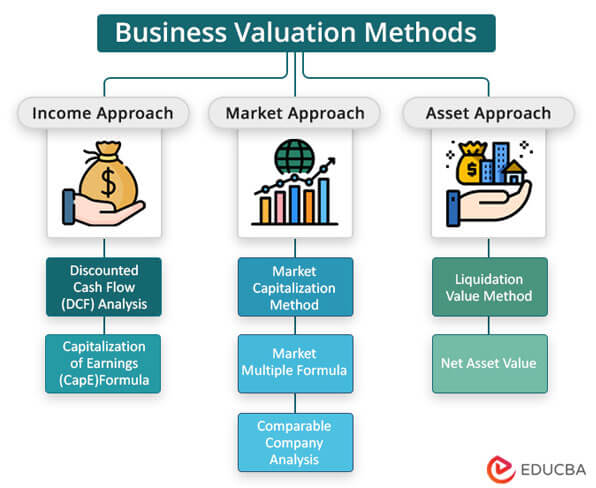

The Three Pillars of Valuation: Core Approaches

While there are many techniques, most valuation methods fall into three broad categories. Understanding these categories is the first step to grasping company valuation.

1. Asset-Based Valuation (What the Company Owns)

This approach focuses on the value of a company’s underlying assets (what it owns) minus its liabilities (what it owes). It’s like valuing a car by adding up the cost of its engine, chassis, tires, etc., and then subtracting any outstanding loans.

When is it typically used?

- Companies with significant tangible assets (e.g., manufacturing, real estate).

- Companies in distress or liquidation, where future earnings are uncertain.

- Early-stage startups with few revenues but valuable intellectual property (IP) or specialized equipment.

Common Techniques:

- Book Value: This is the simplest. It’s the value of assets as recorded on the company’s balance sheet (assets – liabilities – intangible assets). It’s often historical cost and may not reflect current market value.

- Liquidation Value: This estimates what the company’s assets would fetch if they were sold off quickly, often below market value, in a forced sale. It’s a "worst-case scenario" valuation.

- Replacement Cost: This estimates the cost to replace a company’s existing assets with new, similar assets.

Pros:

- Relatively straightforward and objective, especially for tangible assets.

- Useful for companies with predictable asset values.

Cons:

- Doesn’t account for a company’s future earning potential or intangible assets (like brand reputation, customer base, or patents) unless specifically valued.

- Book values can be outdated due to accounting practices.

2. Market-Based Valuation (What Similar Companies are Worth)

This approach, also known as Relative Valuation, compares the target company to similar companies (its "peers" or "comparables") that have recently been sold or are publicly traded. It’s like valuing your house by looking at what similar houses in your neighborhood recently sold for.

When is it typically used?

- Publicly traded companies, where a lot of comparable data is available.

- Companies in mature industries with many similar businesses.

- As a sanity check for other valuation methods.

Common Techniques (using Multiples):

The core idea is to find a relevant financial metric (like earnings or sales) for comparable companies and apply a "multiple" derived from those companies to the target company’s equivalent metric.

- Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio:

- Formula: Share Price / Earnings Per Share (EPS)

- How it works: If comparable companies trade at a P/E of 20x, and your company has EPS of $2, then its estimated share price would be $40 (20 * $2).

- Best for: Mature, profitable companies with stable earnings.

- Enterprise Value to EBITDA (EV/EBITDA):

- Formula: Enterprise Value / Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization

- How it works: EV/EBITDA is often preferred over P/E because it’s less affected by different capital structures and accounting policies. It’s a good measure of operating profitability.

- Best for: Companies across various industries, especially those with significant depreciation/amortization, as it gives a clearer picture of operational cash flow.

- Price-to-Sales (P/S) Ratio:

- Formula: Share Price / Sales Per Share

- How it works: Useful for companies that are not yet profitable but have significant revenue.

- Best for: Growth companies, startups, or companies in industries with high sales volatility but predictable revenue streams.

- Other Multiples: Depending on the industry, you might use Price-to-Book (P/B), Price-to-Free Cash Flow, or industry-specific multiples (e.g., Price per Subscriber for SaaS companies, Revenue per Room for hotels).

Pros:

- Simple and easy to understand.

- Reflects current market sentiment and conditions.

- Provides a quick estimate.

Cons:

- Relies heavily on finding truly comparable companies, which can be challenging.

- Doesn’t account for unique strengths or weaknesses of the target company.

- Market sentiment can be irrational, leading to over or undervaluation.

3. Income-Based Valuation (What the Company Can Earn)

This approach, also known as Intrinsic Valuation, values a company based on its ability to generate future economic benefits, typically cash flow or earnings. It’s considered the most theoretically sound method because a company’s true value lies in the money it can generate for its owners over time.

When is it typically used?

- Most common for established businesses with predictable cash flows.

- For M&A deals, where future synergies are a key consideration.

- For internal strategic planning and capital budgeting.

Key Concepts:

- Time Value of Money: A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow due to inflation and the opportunity to invest it. Income-based methods account for this by "discounting" future cash flows back to their present value.

- Discount Rate: This is the rate used to bring future cash flows back to their present value. It reflects the risk associated with receiving those future cash flows. A higher risk means a higher discount rate and a lower present value. The most common discount rate is the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC).

Common Techniques:

-

a) Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Analysis:

-

This is arguably the most widely used and respected valuation method. It projects a company’s future free cash flows (cash available to investors after all expenses and reinvestments) and discounts them back to their present value using a discount rate (usually WACC).

-

The Logic: A company’s value is the sum of all the cash it’s expected to generate in the future, adjusted for the time value of money and risk.

-

Steps in DCF:

- Forecast Free Cash Flows (FCF): Project the company’s FCF for a specific period (e.g., 5-10 years) based on detailed financial models (revenue growth, expenses, capital expenditures, working capital).

- Calculate Terminal Value (TV): This represents the value of all cash flows beyond the explicit forecast period, assuming the company continues to operate indefinitely. It’s often calculated using a perpetuity growth model or an exit multiple.

- Determine the Discount Rate (WACC): Calculate the company’s Weighted Average Cost of Capital, which reflects the average rate it pays to finance its assets (debt and equity).

- Discount Future Cash Flows: Use the WACC to discount each year’s projected FCF and the Terminal Value back to their present value.

- Sum the Present Values: Add up all the discounted FCFs and the discounted Terminal Value to arrive at the company’s enterprise value. Adjust for debt and cash to get equity value.

-

Pros:

- Considered the most comprehensive and theoretically sound method.

- Accounts for future growth and specific company characteristics.

- Forces detailed analysis of the business.

-

Cons:

- Highly sensitive to assumptions (growth rates, discount rate, terminal value). Small changes can lead to large valuation differences.

- Requires extensive data and financial modeling expertise.

- Less reliable for companies with unpredictable cash flows (e.g., early-stage startups).

-

-

b) Dividend Discount Model (DDM):

- Values a company based on the present value of its future dividend payments.

- Best for: Mature companies with a consistent history of paying dividends. Less useful for companies that reinvest most of their earnings or don’t pay dividends.

-

c) Capitalization of Earnings (Cap of Earnings):

- A simpler income-based method, often used for smaller, stable businesses. It takes a single year’s earnings (or average earnings) and divides it by a "capitalization rate" (which is essentially a required rate of return).

- Formula: Value = Annual Earnings / Capitalization Rate

- Best for: Small businesses with very stable, predictable earnings.

Other Important Considerations in Valuation

Valuation isn’t just about plugging numbers into formulas. There’s a significant "art" to it, which involves understanding qualitative factors and market dynamics.

-

Qualitative Factors:

- Management Team: The quality, experience, and vision of the leadership team.

- Brand Strength: A strong, recognized brand can command a premium.

- Competitive Landscape: The presence of strong competitors or unique competitive advantages.

- Industry Trends: Is the industry growing or declining? Is it facing disruption?

- Intellectual Property (IP): Patents, trademarks, copyrights, and proprietary technology can be hugely valuable.

- Customer Relationships: A loyal, diverse customer base adds significant value.

- Regulatory Environment: Favorable or unfavorable regulations can impact future operations.

-

Assumptions and Sensitivity Analysis:

- Every valuation relies on assumptions about future growth, costs, and market conditions. These assumptions are inherently uncertain.

- Sensitivity analysis involves testing how the valuation changes if key assumptions vary. For example, "What if our revenue growth is 5% instead of 10%?" This helps identify the most critical assumptions and the range of possible values.

-

The "Art" vs. "Science":

- The "science" is the formulas and calculations. The "art" is in selecting the right method, choosing appropriate comparable companies, making reasonable assumptions, and interpreting the results in context. No single valuation number is perfect; it’s always an estimate.

Choosing the Right Valuation Method

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. The best method depends on the specific circumstances of the company and the purpose of the valuation:

- Early-Stage Startups (pre-revenue): Often rely on Asset-Based (for IP/assets), market multiples based on user growth or potential, or venture capital methods (e.g., pre-money/post-money valuation based on funding rounds). DCF is usually difficult due to lack of predictable cash flows.

- Mature, Stable Businesses: DCF and Market Multiples are highly relevant due to predictable cash flows and available comparable data.

- Companies with Significant Tangible Assets: Asset-Based valuation becomes more important.

- Companies in Niche Industries: Market multiples can be challenging if few true comparables exist. DCF might be more reliable.

- For a Quick Estimate: Market multiples are often used.

- For a Deep Dive & Investment Decision: DCF is usually preferred, often cross-checked with market multiples.

It’s common practice to use multiple valuation methods and then reconcile the results to arrive at a fair value range. This "triangulation" helps provide a more robust and reliable estimate.

Conclusion: Your Journey into Valuation

Company valuation is a cornerstone of finance and business. While it might seem daunting at first, breaking it down into its core components – asset, market, and income-based approaches – makes it much more accessible.

Remember that valuation is more than just crunching numbers; it’s about understanding the underlying business, its industry, its competitive advantages, and its future potential. By grasping these fundamental methods and techniques, you’ll be better equipped to make informed decisions, whether you’re looking to invest, raise capital, or simply understand the true worth of a business.

The journey to mastering valuation is continuous, but with this guide, you’ve taken a significant first step into unlocking the true worth of companies.

Post Comment