What is Inflation? Understanding Its Causes, Effects, and How It’s Measured (A Beginner’s Guide)

Have you ever noticed that your favorite candy bar seems to shrink while its price stays the same, or that a gallon of milk costs more than it did a few years ago? This common experience is a direct symptom of something called inflation. It’s a word you hear often in the news, but what does it really mean, and why does it matter to your wallet?

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll demystify inflation, breaking down its definition, exploring the various forces that cause prices to rise, examining its profound effects on individuals and the economy, and explaining how economists measure this crucial economic indicator. Whether you’re a student, a consumer, or just curious, this article will equip you with a solid understanding of inflation.

Table of Contents

- What Exactly Is Inflation?

- The "Invisible Tax"

- Understanding Purchasing Power

- The Main Types of Inflation

- Demand-Pull Inflation

- Cost-Push Inflation

- What Causes Inflation? Unpacking the Drivers

- Too Much Money Chasing Too Few Goods (Demand-Pull)

- Rising Production Costs (Cost-Push)

- Government Spending and Fiscal Policy

- Monetary Policy and the Money Supply

- Inflationary Expectations

- Supply Chain Disruptions and Global Events

- The Effects of Inflation: Good, Bad, and Ugly

- Negative Effects:

- Reduced Purchasing Power & Cost of Living Crisis

- Uncertainty and Reduced Investment

- Erosion of Savings

- Fixed Income Earners Suffer

- Redistribution of Wealth

- International Competitiveness

- Potential Positive Effects (Why a Little is Okay):

- Encourages Spending and Investment

- Reduces the Real Burden of Debt

- Provides Flexibility for Wages

- Negative Effects:

- How Is Inflation Measured? The Economist’s Toolkit

- The "Basket of Goods and Services"

- Key Inflation Metrics:

- Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- Producer Price Index (PPI)

- Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index

- Calculating the Inflation Rate

- Who Benefits and Who Loses from Inflation?

- Managing Inflation: What Can Be Done?

- Monetary Policy

- Fiscal Policy

- Supply-Side Policies

- Conclusion: Navigating the Economic Waters

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Inflation

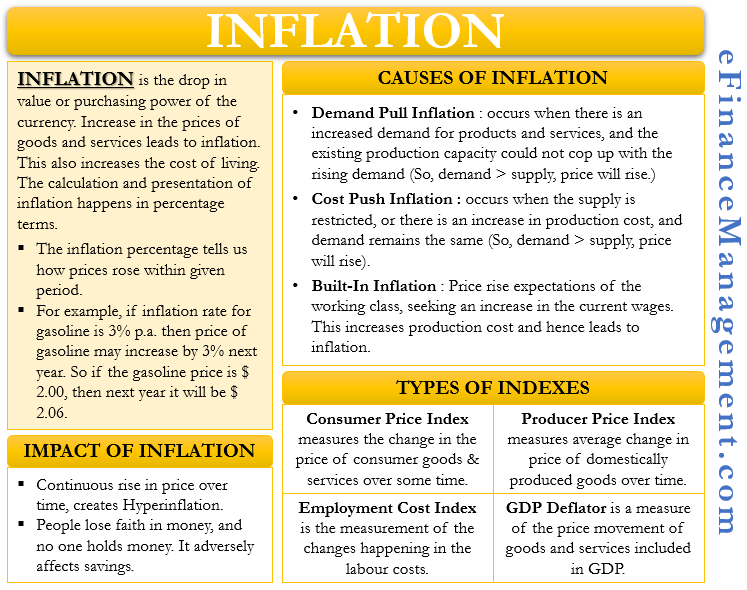

1. What Exactly Is Inflation?

At its core, inflation is the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and consequently, the purchasing power of currency is falling. Think of it as your money buying less and less over time.

Imagine you have $100. If a basket of groceries that cost $100 last year now costs $105, then inflation has occurred. Your $100 can no longer buy that same basket of groceries.

The "Invisible Tax"

Many economists refer to inflation as an "invisible tax." Unlike a direct tax on your income or purchases, inflation silently erodes the value of your money. You don’t see a specific deduction, but your hard-earned dollars simply don’t go as far as they used to.

Understanding Purchasing Power

The most critical concept to grasp when thinking about inflation is purchasing power.

- Purchasing power refers to the amount of goods and services that can be bought with a unit of currency.

- When inflation is high, your currency’s purchasing power decreases, meaning you need more money to buy the same items.

- When inflation is low or non-existent, your money retains its value, or even increases in value (in the case of deflation).

In simple terms: Inflation means your money is worth less tomorrow than it is today.

2. The Main Types of Inflation

While many factors can contribute to rising prices, economists generally categorize the causes of inflation into two main types:

Demand-Pull Inflation

This type of inflation occurs when there is too much money chasing too few goods. It happens when the overall demand for goods and services in an economy outstrips the available supply. Think of it like a popular concert where everyone wants tickets, driving up the price because demand is so high.

- Key characteristic: Strong consumer demand, often fueled by increased money supply or government spending.

- Analogy: A bidding war – buyers are eager, so sellers can raise prices.

Cost-Push Inflation

Cost-push inflation happens when the cost of producing goods and services increases, leading businesses to raise their prices to maintain profit margins. It’s not about too much demand, but about higher expenses for the producers.

- Key characteristic: Rising input costs (e.g., raw materials, wages, energy).

- Analogy: A baker’s flour and sugar prices go up, so they have to charge more for a loaf of bread.

3. What Causes Inflation? Unpacking the Drivers

Now, let’s dive deeper into the specific factors that can lead to demand-pull or cost-push inflation.

Too Much Money Chasing Too Few Goods (Demand-Pull)

This is the classic explanation for inflation. When people have more money to spend (or can borrow more easily), they tend to buy more. If the supply of goods and services doesn’t increase at the same pace, prices will naturally rise.

- Examples:

- Government Stimulus Checks: When governments inject money directly into the economy, consumers have more cash, boosting demand.

- Increased Consumer Confidence: If people feel secure about their jobs and the economy, they’re more likely to spend and borrow.

- Rapid Economic Growth: A booming economy with low unemployment often leads to higher wages and more consumer spending.

Rising Production Costs (Cost-Push)

When the cost of producing goods and services goes up, businesses face a choice: absorb the higher costs (and potentially reduce profits) or pass them on to consumers through higher prices. Most often, they choose the latter.

- Examples:

- Higher Raw Material Prices: An increase in the price of oil, metals, or agricultural products makes everything from transportation to manufacturing more expensive.

- Increased Wages: If workers demand and receive higher wages, businesses’ labor costs rise, which can be passed on to consumers.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Events like natural disasters, pandemics, or geopolitical conflicts can disrupt the flow of goods, making components or finished products scarcer and thus more expensive.

- Higher Taxes or Regulations: New taxes on businesses or stricter environmental regulations can increase operating costs.

Government Spending and Fiscal Policy

When a government spends more than it collects in taxes (runs a deficit), it often has to borrow money or, in some cases, print more money (though this is less common in modern developed economies).

- Increased Demand: Large government spending projects (e.g., infrastructure, defense) directly increase demand for goods and services.

- Money Supply Expansion: If the government prints more money without a corresponding increase in goods and services, the value of each unit of currency falls.

Monetary Policy and the Money Supply

Central banks (like the Federal Reserve in the U.S. or the European Central Bank) control the money supply in an economy. They use tools to influence how much money is available and how easily it can be borrowed.

- Lower Interest Rates: When central banks lower interest rates, borrowing becomes cheaper for businesses and consumers. This encourages spending and investment, increasing the money supply and potentially leading to demand-pull inflation.

- Quantitative Easing (QE): This involves the central bank buying large quantities of government bonds or other financial assets, injecting money directly into the financial system.

Inflationary Expectations

One of the trickiest causes of inflation is inflationary expectations. If people expect prices to rise in the future, they might:

- Demand higher wages: Workers will ask for more pay to compensate for anticipated higher living costs.

- Businesses raise prices: Companies might preemptively increase prices, assuming their costs will go up.

- Consumers buy now: People might accelerate purchases to beat future price hikes.

This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy, where the expectation of inflation actually causes inflation.

Supply Chain Disruptions and Global Events

In an increasingly interconnected world, events far away can have a direct impact on local prices.

- Wars or Conflicts: Can disrupt trade routes, reduce production of key commodities (like oil or grain), and lead to sanctions that limit supply.

- Pandemics: As seen with COVID-19, widespread illness can shut down factories, ports, and transportation networks, creating bottlenecks and driving up prices.

- Natural Disasters: Hurricanes, floods, or earthquakes can destroy crops, infrastructure, or production facilities, limiting supply and raising prices.

4. The Effects of Inflation: Good, Bad, and Ugly

Inflation is a double-edged sword. While hyperinflation can be catastrophic, a small, controlled amount of inflation is often considered healthy for an economy.

Negative Effects of High or Uncontrolled Inflation:

When inflation gets out of control, its negative impacts become very apparent:

- Reduced Purchasing Power & Cost of Living Crisis:

- This is the most direct and painful effect. Your money simply buys less.

- Salaries may not keep pace with rising prices, leading to a decline in real income (what you can actually afford).

- This can lead to a cost of living crisis, where essential goods become unaffordable for many.

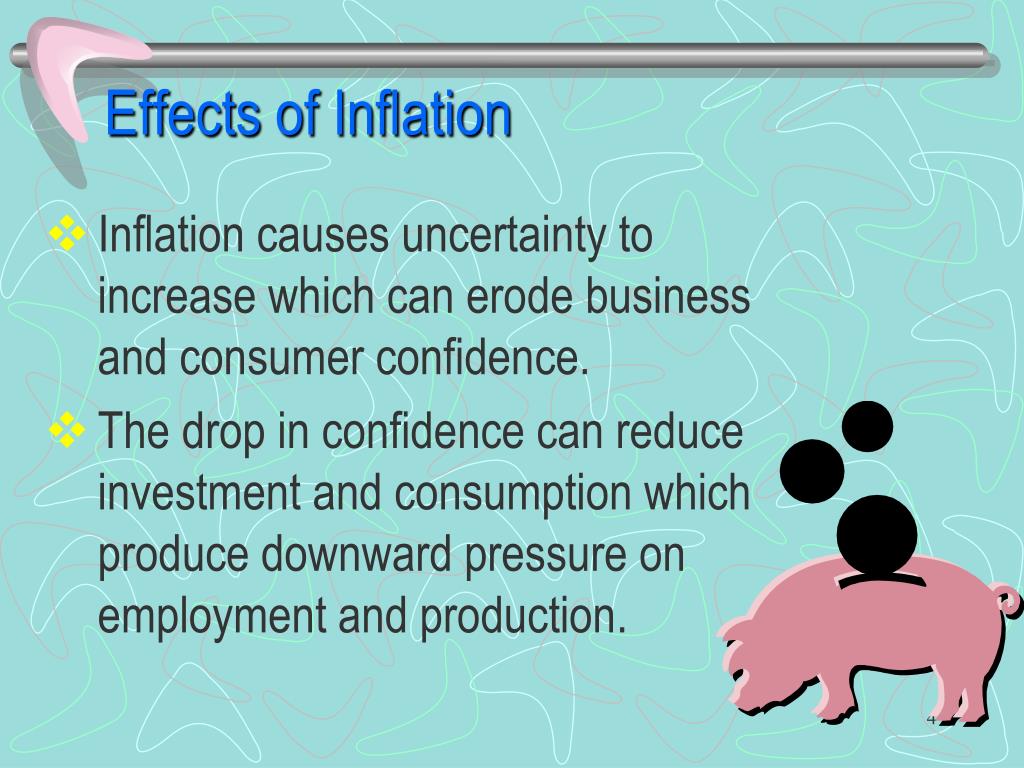

- Uncertainty and Reduced Investment:

- Businesses become hesitant to invest in new projects when future costs and revenues are unpredictable.

- Consumers may delay large purchases due to economic uncertainty.

- This can slow down economic growth and job creation.

- Erosion of Savings:

- Money held in savings accounts or under the mattress loses value over time if the interest rate earned is lower than the inflation rate.

- Savers, especially retirees on fixed incomes, see their life savings diminish in real terms.

- Fixed Income Earners Suffer:

- Individuals on fixed pensions, annuities, or long-term contracts (where payments don’t adjust for inflation) find their real income shrinking.

- Redistribution of Wealth:

- Inflation tends to benefit borrowers at the expense of lenders. If you borrow money at a fixed interest rate, and inflation rises, the money you pay back is worth less than the money you borrowed.

- It can also redistribute wealth from the poor (who often hold cash or have fewer inflation-protected assets) to the rich (who may own assets like real estate or stocks that tend to appreciate with inflation).

- International Competitiveness:

- If a country’s inflation rate is higher than its trading partners, its goods become relatively more expensive for foreign buyers.

- This can hurt exports and worsen the trade balance.

Potential Positive Effects (Why a Little Inflation is Okay):

A moderate, predictable level of inflation (often around 2-3% per year) is generally considered healthy and desirable by central banks for several reasons:

- Encourages Spending and Investment:

- Knowing that money will be worth slightly less in the future encourages people to spend or invest it now rather than hoard cash. This keeps money flowing through the economy.

- Reduces the Real Burden of Debt:

- For individuals, businesses, and governments with fixed-rate debt, inflation effectively reduces the "real" (inflation-adjusted) amount they owe. This can make debt more manageable.

- Provides Flexibility for Wages:

- In a low-inflation environment, it can be difficult for companies to cut nominal wages (the actual dollar amount paid) without causing resentment.

- With moderate inflation, companies can effectively reduce "real" wages (what the wage can buy) even if nominal wages stay the same or rise slightly, without needing to cut the dollar amount, which can help adjust to economic downturns.

- Avoids Deflation:

- Deflation (falling prices) is generally considered much worse than moderate inflation. It encourages people to delay purchases (waiting for prices to fall further), leading to reduced demand, production cuts, unemployment, and economic stagnation.

5. How Is Inflation Measured? The Economist’s Toolkit

Measuring inflation isn’t as simple as checking the price of a single item. Economists use sophisticated methods to track the general price level across a wide range of goods and services.

The "Basket of Goods and Services"

The core concept behind inflation measurement is the "basket of goods and services." Imagine a typical shopping cart filled with items that an average household buys regularly. This basket includes:

- Food and beverages

- Housing (rent, mortgage payments, utilities)

- Transportation (gas, car prices, public transport)

- Medical care

- Education

- Apparel

- Recreation

- Other goods and services

Economists track the prices of these items over time to see how much the cost of this "typical" basket changes.

Key Inflation Metrics:

Several indices are used to measure inflation, each with a slightly different focus:

1. Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- What it is: The most widely cited measure of inflation. It tracks the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services.

- Who compiles it: In the U.S., the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

- Why it matters: It directly reflects changes in the cost of living for most people and is used to adjust Social Security benefits, pension payments, and other government programs.

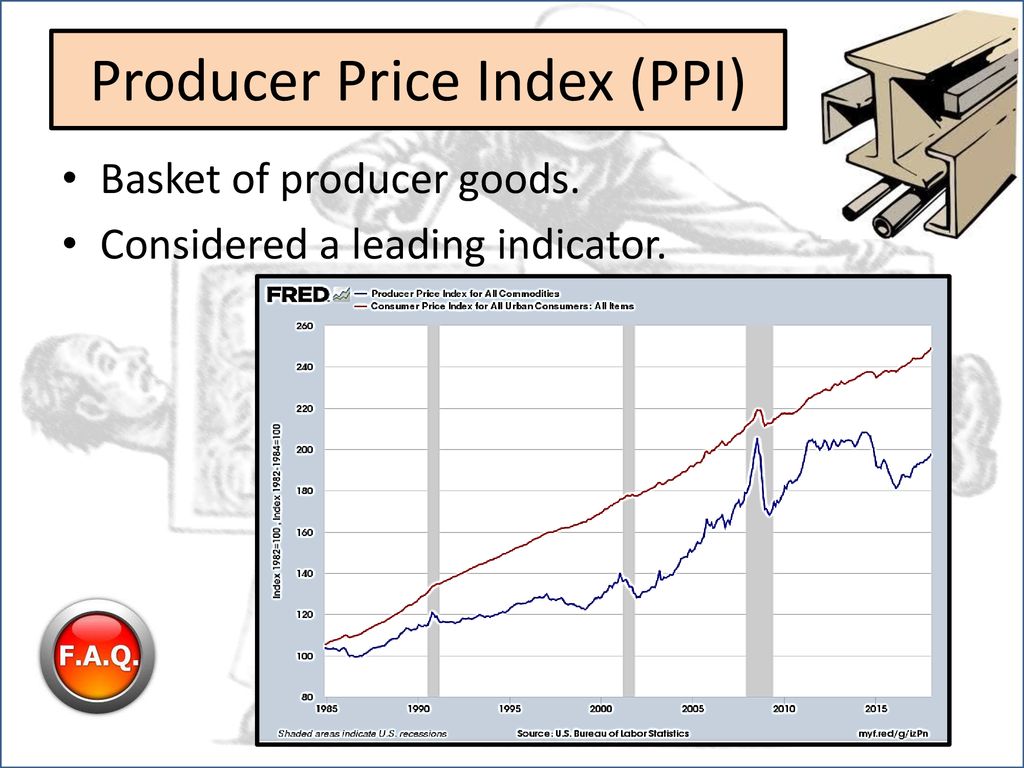

2. Producer Price Index (PPI)

- What it is: Measures the average change over time in the selling prices received by domestic producers for their output. It tracks prices at the wholesale level.

- Why it matters: PPI can be a leading indicator for future CPI. If producers’ costs are rising, they will likely pass those costs on to consumers eventually.

3. Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index

- What it is: A measure of the prices of goods and services purchased by consumers, similar to CPI, but with some key differences. It’s compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

- Why it matters: The Federal Reserve (U.S. central bank) often prefers the PCE index as its primary inflation gauge because:

- It accounts for changes in consumer behavior (e.g., if the price of beef rises, consumers might switch to chicken, and PCE reflects this substitution).

- It has a broader coverage of goods and services than CPI.

Calculating the Inflation Rate

Once the price of the "basket" is tracked over time, the inflation rate is calculated as the percentage change in the price index from one period to another.

Simple Formula:

$$ textInflation Rate = fractext(Current Index Value – Previous Index Value)textPrevious Index Value times 100% $$

For example, if the CPI was 280 in January 2022 and 290 in January 2023, the annual inflation rate would be:

$$ fractext(290 – 280)text280 times 100% = frac10280 times 100% approx 3.57% $$

This means that, on average, prices rose by about 3.57% over that year.

6. Who Benefits and Who Loses from Inflation?

Inflation doesn’t affect everyone equally. Its impact depends heavily on your financial situation and how you hold your assets.

Losers from Inflation:

- Savers: If the interest rate on their savings account is lower than the inflation rate, their money loses purchasing power.

- Fixed Income Earners: Retirees, pensioners, and anyone on a fixed salary or payment schedule will see their real income decline.

- Creditors/Lenders: Those who lend money (e.g., banks, bondholders) receive back money that is worth less in real terms than when they lent it.

- People Holding Cash: The value of physical cash erodes with inflation.

Winners (or Less Affected) by Inflation:

- Borrowers/Debtors: Those who have borrowed money at fixed interest rates benefit because the real value of their debt decreases over time. The money they pay back is worth less than the money they originally borrowed.

- Asset Owners (sometimes): Owners of real assets like real estate, commodities, or stocks may see the value of their assets rise with inflation, acting as a hedge. However, this is not guaranteed, and asset prices can fluctuate for many reasons.

- Governments: As large debtors, governments can benefit from inflation as it reduces the real burden of their national debt. They can also collect more tax revenue if nominal incomes and prices rise.

7. Managing Inflation: What Can Be Done?

Controlling inflation is a primary goal of economic policymakers. They primarily use two sets of tools:

Monetary Policy (Central Banks)

Central banks are the frontline defenders against high inflation. Their main tools include:

- Interest Rate Adjustments: The most common tool. Raising interest rates makes borrowing more expensive, which discourages spending and investment, thus cooling down demand. Lowering rates does the opposite.

- Controlling the Money Supply: Central banks can buy or sell government bonds (Open Market Operations) to increase or decrease the amount of money circulating in the economy.

- Reserve Requirements: Adjusting the percentage of deposits banks must hold in reserve can influence how much money banks have available to lend.

Fiscal Policy (Government)

Governments can also influence inflation through their spending and taxation policies:

- Reduced Government Spending: If the government cuts back on its own spending, it reduces overall demand in the economy.

- Increased Taxes: Raising taxes leaves consumers and businesses with less disposable income, which can curb spending and demand.

Supply-Side Policies

These policies aim to increase the economy’s productive capacity, thereby increasing the supply of goods and services to meet demand. These are typically long-term solutions.

- Investment in Infrastructure: Improved roads, ports, and communication networks can make production and distribution more efficient.

- Education and Training: A more skilled workforce can increase productivity.

- Deregulation: Reducing unnecessary regulations can lower business costs and encourage production.

- Promoting Competition: Breaking up monopolies can prevent price gouging.

8. Conclusion: Navigating the Economic Waters

Inflation is a fundamental concept in economics that directly impacts your daily life and financial well-being. It’s not just a number on a chart; it dictates how far your money goes, influences your savings, and shapes your economic decisions.

While rampant inflation can be destructive, a moderate, stable level is often seen as a sign of a healthy, growing economy. Understanding its causes, effects, and how it’s measured empowers you to make informed financial choices and better comprehend the economic news that shapes our world. By keeping an eye on inflation, you’re better equipped to navigate the ever-changing economic waters.

9. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Inflation

Q1: What is a "good" inflation rate?

Most central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, aim for an annual inflation rate of around 2%. This level is considered healthy because it’s high enough to avoid deflation (which is generally worse for the economy) but low enough to maintain price stability and not erode purchasing power too quickly.

Q2: Is inflation always bad?

No, not necessarily. While high or unpredictable inflation is detrimental, a small, stable amount of inflation (e.g., 2-3%) is often considered beneficial. It encourages spending and investment, reduces the real burden of debt, and provides economic flexibility, helping to avoid the pitfalls of deflation.

Q3: What is the difference between inflation, deflation, and disinflation?

- Inflation: A general increase in prices and a fall in the purchasing value of money.

- Deflation: A general decrease in prices and an increase in the purchasing value of money. This can sound good but often leads to reduced spending, production cuts, and higher unemployment as people delay purchases waiting for prices to fall further.

- Disinflation: A slowdown in the rate of inflation. Prices are still rising, but at a slower pace than before. For example, if inflation drops from 5% to 3%, that’s disinflation.

Q4: What is hyperinflation?

Hyperinflation is an extremely rapid, out-of-control increase in prices. It’s usually defined as inflation exceeding 50% per month. Hyperinflation causes money to rapidly lose its value, leading to economic collapse, social unrest, and a return to bartering. Examples include Weimar Germany in the 1920s, Zimbabwe in the 2000s, and Venezuela more recently.

Q5: How can I protect my savings from inflation?

While no strategy is foolproof, here are some common ways people try to protect their money from inflation:

- Invest in Inflation-Protected Securities: Like Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) in the U.S., which adjust their principal value based on inflation.

- Invest in Real Assets: Real estate, commodities (like gold or oil), and some types of stocks (especially those of companies that can easily pass on higher costs to consumers) can sometimes act as a hedge against inflation.

- Diversify Your Investments: A well-diversified portfolio across different asset classes can offer some protection.

- Consider Shorter-Term Debt: If interest rates are rising due to inflation, holding shorter-term bonds or savings accounts that reset rates more frequently can be beneficial.

- Invest in Yourself: Enhancing your skills and earning potential can help your income keep pace with or exceed inflation.

Post Comment