Central Bank Interest Rate Policies Explained: A Beginner’s Guide to Monetary Policy

Have you ever wondered why your mortgage rate changes, or why news anchors constantly discuss "interest rate hikes" or "cuts" from the Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank? These discussions revolve around one of the most powerful levers in the global economy: Central Bank Interest Rate Policies.

Far from being an arcane topic reserved for economists, understanding how central banks manage interest rates is crucial for anyone looking to grasp the dynamics of their personal finances, the housing market, stock investments, and even job prospects.

This comprehensive guide will demystify central bank interest rate policies, breaking down complex concepts into easy-to-understand language. We’ll explore what central banks are, why interest rates matter, how they are controlled, and the profound ripple effects their decisions have on your everyday life.

What Exactly is a Central Bank? The Economy’s Orchestra Conductor

Before diving into interest rates, let’s establish what a central bank is. Think of a central bank as the financial backbone and conductor of a country’s (or a region’s) economy. Unlike commercial banks (like your local bank where you have an account), central banks don’t typically deal directly with the public. Their clients are commercial banks and the government itself.

Key Roles of a Central Bank:

- Issuing Currency: They are responsible for printing and distributing a nation’s money.

- Banker to the Government: They manage the government’s accounts and debt.

- Banker to Banks: They provide services to commercial banks, including lending them money and holding their reserves.

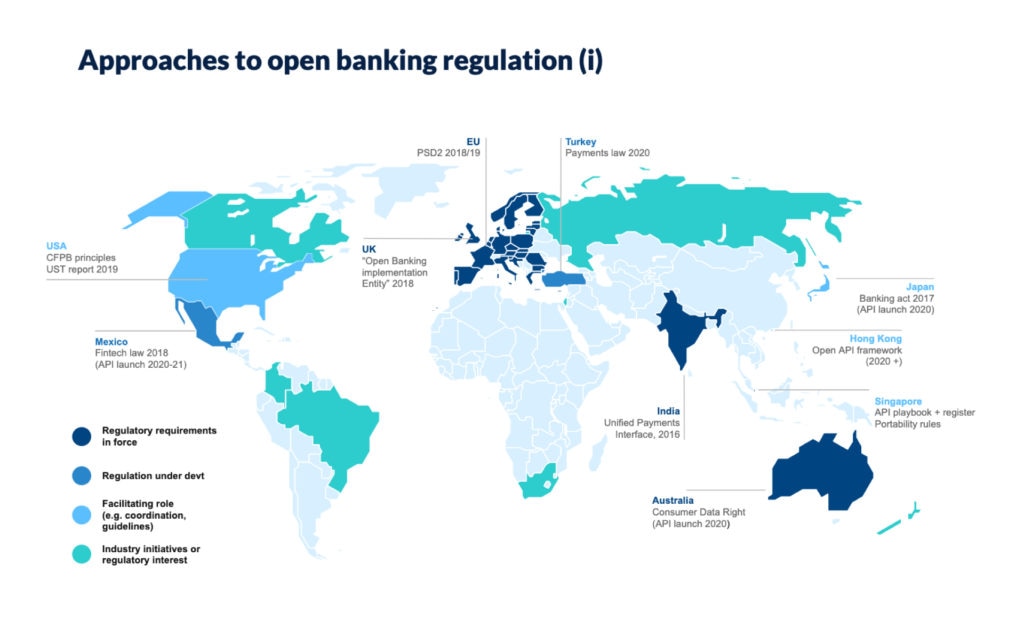

- Regulating the Banking System: They set rules and oversee banks to ensure stability and protect consumers.

- Maintaining Financial Stability: Their most critical role, often achieved through monetary policy.

Examples of Major Central Banks:

- The Federal Reserve (The Fed): For the United States.

- The European Central Bank (ECB): For the Eurozone countries.

- The Bank of England (BoE): For the United Kingdom.

- The Bank of Japan (BoJ): For Japan.

- The People’s Bank of China (PBOC): For China.

Understanding Interest Rates: The Price of Money

At its simplest, an interest rate is the cost of borrowing money or the return on saving money.

- When you borrow money (e.g., a mortgage, car loan), the interest rate is the extra amount you pay on top of the principal amount.

- When you save money (e.g., in a savings account, bond), the interest rate is the return you earn on your deposit.

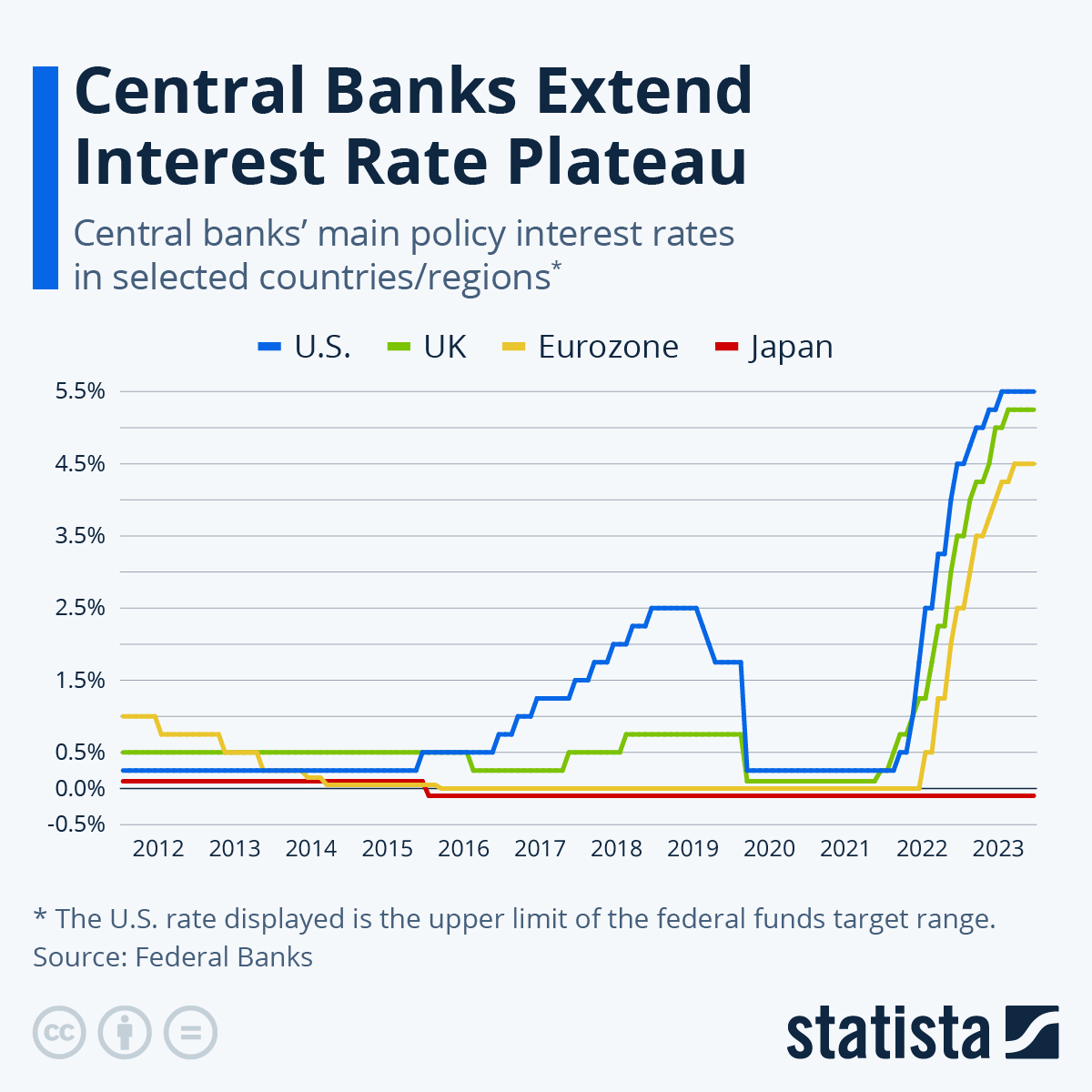

Central banks don’t directly set the interest rate on your car loan or savings account. Instead, they influence a very specific, foundational interest rate known as the "policy rate" (or sometimes the "benchmark rate" or "key interest rate"). This policy rate then acts as a ripple, influencing all other interest rates throughout the economy.

Think of it like this: If the central bank sets the price of money for banks, then banks will adjust their own lending and saving rates to reflect that cost.

The Primary Goals of Central Bank Interest Rate Policies (Monetary Policy)

Central banks use interest rate policies as part of their broader monetary policy toolkit to achieve specific macroeconomic goals. While exact mandates can vary slightly by country, the core objectives are generally the same:

-

Price Stability (Controlling Inflation): This is often considered the primary goal. Inflation is the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and purchasing power is falling.

- Too much inflation erodes savings and makes economic planning difficult.

- Too little inflation (deflation) can also be harmful, leading to delayed spending and economic stagnation.

- Central banks typically aim for a low, stable rate of inflation (e.g., around 2% per year).

-

Maximum Sustainable Employment: Central banks also strive to foster conditions that lead to low unemployment and a healthy job market.

- When the economy is growing robustly, businesses hire more, leading to lower unemployment.

-

Moderate Long-Term Interest Rates: While they directly influence short-term rates, central banks also aim for an environment where long-term interest rates (like those on mortgages) are stable and conducive to investment and growth.

The Balancing Act: Often, these goals can be in tension. For example, boosting employment might risk higher inflation, and controlling inflation might temporarily slow job growth. Central bankers constantly walk a tightrope, trying to find the optimal balance.

How Central Banks Influence Interest Rates: The Tools of the Trade

Central banks have several powerful tools at their disposal to influence the policy rate and, by extension, the broader economy.

1. The Policy Rate (The Most Important Tool)

This is the rate that receives the most attention. Different central banks have different names for their policy rate:

- Federal Funds Rate (U.S. Federal Reserve): The target rate for overnight lending between banks.

- Main Refinancing Operations Rate (European Central Bank): The rate at which commercial banks can borrow money from the ECB for one week.

- Bank Rate (Bank of England): The interest rate the BoE charges banks for secured overnight lending.

How it works:

When the central bank changes this rate, it directly affects the cost of borrowing for commercial banks.

- Higher Policy Rate: Banks pay more to borrow from each other or the central bank, so they charge their customers (businesses and individuals) more for loans.

- Lower Policy Rate: Banks pay less, so they can offer cheaper loans to their customers.

This is the primary way central banks signal their stance on monetary policy.

2. Open Market Operations (OMOs)

OMOs are the buying and selling of government securities (like bonds) in the open market. This is the most frequently used tool to manage the money supply.

-

To Lower Interest Rates (Increase Money Supply): The central bank buys government bonds from commercial banks.

- When the central bank buys bonds, it pays banks by crediting their reserve accounts.

- This increases the amount of money banks have available to lend, pushing down the interest rate on those loans.

- Analogy: Injecting more water into a pool makes the water cheaper to access.

-

To Raise Interest Rates (Decrease Money Supply): The central bank sells government bonds to commercial banks.

- When the central bank sells bonds, banks pay for them by drawing down their reserve accounts.

- This reduces the amount of money banks have available to lend, making money scarcer and thus more expensive.

- Analogy: Draining water from a pool makes the remaining water more valuable.

3. Reserve Requirements

This tool dictates the minimum amount of money that commercial banks must hold in reserve (either in their vaults or at the central bank) against their deposits, rather than lending out.

- Increasing Reserve Requirements: Banks have less money to lend, which tends to push interest rates up.

- Decreasing Reserve Requirements: Banks have more money to lend, which tends to push interest rates down.

Note: This tool is used less frequently than OMOs or policy rate changes because it can be quite disruptive to banks’ operations.

4. The Discount Window / Standing Facilities

This refers to the facility where commercial banks can borrow money directly from the central bank, usually for very short periods (e.g., overnight) to meet sudden liquidity needs. The interest rate charged on these loans is called the discount rate (or marginal lending facility rate in the Eurozone).

- How it works: While banks prefer to borrow from each other at the policy rate, the discount window provides a backstop.

- The discount rate is typically set slightly higher than the policy rate to discourage overuse and to act as a ceiling for short-term interbank rates. A change in the discount rate can also signal the central bank’s stance.

5. Unconventional Tools (Especially Post-2008 & COVID-19)

When traditional tools aren’t enough (e.g., during severe recessions when policy rates are already at or near zero), central banks may resort to unconventional measures:

-

Quantitative Easing (QE): The central bank buys large quantities of long-term government bonds or other assets from the market.

- Goal: To push down long-term interest rates (like mortgage rates) and inject massive amounts of liquidity directly into the financial system, stimulating lending and investment.

- Think of it as: A much larger, broader version of Open Market Operations, often targeting longer-term assets.

-

Quantitative Tightening (QT): The opposite of QE. The central bank reduces its holdings of bonds, either by selling them or by letting them mature without reinvesting the proceeds.

- Goal: To reduce the money supply, withdraw liquidity, and allow long-term interest rates to rise, often used to combat high inflation.

-

Forward Guidance: Central banks communicate their future intentions regarding interest rates and monetary policy.

- Goal: To influence market expectations and provide clarity, helping to stabilize markets and guide economic behavior.

The Ripple Effect: How Interest Rate Changes Impact You and the Economy

Changes in the central bank’s policy rate don’t just affect banks; they send ripples throughout the entire economy, impacting businesses, consumers, and financial markets.

1. Borrowing Costs for Consumers & Businesses

- Mortgages: When the central bank raises rates, banks typically raise their prime lending rate, which influences variable-rate mortgages and makes new fixed-rate mortgages more expensive. Lower rates mean cheaper mortgages.

- Car Loans, Personal Loans, Credit Cards: Interest rates on these types of consumer credit also tend to rise or fall in line with central bank policy.

- Business Loans: Companies seeking loans for expansion, new equipment, or inventory will face higher or lower borrowing costs, impacting their investment decisions.

2. Savings & Investments

- Savings Accounts & CDs: When central banks raise rates, banks typically offer higher interest rates on savings accounts and Certificates of Deposit (CDs), making saving more attractive. Lower rates mean lower returns on savings.

- Bonds: Bond prices and interest rates move inversely. When interest rates rise, newly issued bonds offer higher yields, making older, lower-yielding bonds less attractive (their price falls).

- Stocks: The impact on stocks is more complex:

- Higher Rates: Can make borrowing more expensive for companies (reducing profits), make bonds more attractive than stocks, and can reduce consumer spending. Generally seen as negative for stock prices.

- Lower Rates: Can boost corporate profits (cheaper borrowing), make stocks more attractive than bonds, and encourage consumer spending. Generally seen as positive for stock prices.

3. Consumer Spending & Economic Growth

- Higher Rates: Make borrowing more expensive and saving more attractive. This tends to reduce consumer spending and business investment, slowing down economic growth and cooling inflation. (Think: putting the brakes on the economy).

- Lower Rates: Make borrowing cheaper and saving less rewarding. This encourages consumers to spend (e.g., buy a house, car) and businesses to invest, stimulating economic growth and potentially leading to higher employment. (Think: stepping on the gas).

4. Exchange Rates

- Higher Rates: Can attract foreign investment seeking better returns, increasing demand for the domestic currency and strengthening its value relative to other currencies.

- Lower Rates: Can make a country less attractive for foreign investment, potentially leading to a weaker currency.

- Impact: A stronger currency makes imports cheaper and exports more expensive, affecting international trade.

5. Inflation

- Higher Rates (Anti-Inflationary): By slowing down the economy, reducing demand, and making borrowing more expensive, higher rates help to bring down inflation.

- Lower Rates (Inflationary Pressure): By stimulating demand and making money cheaper, lower rates can contribute to higher inflation.

When Do Central Banks Raise Rates? (The "Tightening" Cycle)

Central banks typically raise interest rates (a process known as monetary tightening or a rate hike cycle) when:

- Inflation is too high or rising rapidly: This is the primary trigger. If prices are spiraling out of control, higher rates are used to cool down demand and bring inflation back to target.

- The economy is "overheating": This means economic growth is very strong, unemployment is very low, and there’s a risk of inflation accelerating.

- To curb speculative bubbles: Sometimes, rising asset prices (like in housing or stocks) can become unsustainable. Higher rates can help deflate such bubbles.

The Goal: To slow down the economy just enough to control inflation without triggering a recession. It’s a delicate balancing act.

When Do Central Banks Lower Rates? (The "Easing" Cycle)

Central banks typically lower interest rates (a process known as monetary easing or a rate cut cycle) when:

- Economic growth is slowing down or entering a recession: Lower rates encourage borrowing and spending, providing a boost to economic activity.

- Unemployment is rising or too high: Stimulating the economy helps create jobs.

- Inflation is too low (deflation risk): If prices are falling, lower rates can encourage demand and help bring inflation back to target.

- During financial crises: Lower rates can provide liquidity and stability to financial markets.

The Goal: To stimulate economic activity, encourage investment, and boost employment.

Navigating the Nuances: Challenges and Considerations

Central bank interest rate policy isn’t a simple science. Several factors make it complex:

- Lag Effects: Monetary policy decisions don’t impact the economy immediately. There’s a significant time lag (often 12-18 months) before the full effects are felt. This makes timing decisions very difficult.

- Global Economy: A country’s economy is not isolated. Global economic conditions, trade wars, and international capital flows can all influence the effectiveness of domestic interest rate policies.

- Market Expectations: Financial markets often "price in" anticipated rate changes even before the central bank makes them. This can sometimes front-run the central bank’s intentions.

- Political Pressure: Central banks aim to be independent, but they can face political pressure, especially during economic downturns or periods of high inflation.

- Uncertainty: Economic data can be volatile and difficult to interpret, making it challenging to predict future economic conditions with certainty.

Conclusion: Why Central Bank Decisions Matter to You

Central bank interest rate policies are the invisible hand guiding much of our economic lives. From the size of your monthly mortgage payment to the returns on your savings, and from the hiring decisions of local businesses to the stability of the entire financial system, these decisions resonate deeply.

By understanding the basic principles of how central banks operate and the tools they use, you gain a valuable perspective on economic news, financial markets, and the forces that shape your personal financial landscape. It’s not just for economists; it’s essential knowledge for anyone navigating the modern economy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is "monetary policy"?

A1: Monetary policy refers to the actions undertaken by a central bank to influence the availability and cost of money and credit to help promote national economic goals. Interest rate policies are a key component of monetary policy.

Q2: Who sets the interest rates at a central bank?

A2: Typically, a committee within the central bank. For example, in the U.S., it’s the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve. In the Eurozone, it’s the Governing Council of the ECB. These committees meet regularly to assess economic conditions and make policy decisions.

Q3: How often do central banks change interest rates?

A3: It varies, but major central banks usually have scheduled meetings (e.g., every 6-8 weeks) where they review economic data and decide on policy changes. In times of crisis, they can make unscheduled announcements.

Q4: What is a "rate hike" versus a "rate cut"?

A4:

- Rate Hike: When a central bank increases its policy interest rate, making borrowing more expensive and encouraging saving.

- Rate Cut: When a central bank decreases its policy interest rate, making borrowing cheaper and encouraging spending and investment.

Q5: Does a central bank’s interest rate decision directly affect my mortgage rate?

A5: Yes, indirectly but significantly. While the central bank doesn’t set your specific mortgage rate, its policy rate heavily influences the rates that commercial banks offer. Variable-rate mortgages will often adjust quickly, while fixed-rate mortgages are influenced by long-term interest rate trends, which are also shaped by central bank policy and expectations.

Q6: What happens if a central bank lowers rates too much?

A6: Lowering rates too much can lead to excessive inflation, asset bubbles (e.g., in housing or stock markets), and can create financial instability by encouraging excessive risk-taking.

Q7: What happens if a central bank raises rates too much?

A7: Raising rates too much can stifle economic growth, lead to a recession, and increase unemployment. It can also make debt more expensive for governments and businesses, potentially leading to financial distress.

Post Comment