The Evolution of Global Economic Models: A Journey Through Humanity’s Economic Story

Have you ever wondered why some countries are rich and others poor? Or why governments sometimes spend a lot and other times cut back? The answers often lie in the underlying "economic model" a society adopts. An economic model is essentially the framework a society uses to organize the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. It dictates who owns what, how decisions are made, and how wealth is created and shared.

Understanding these models isn’t just for economists; it’s crucial for anyone wanting to make sense of our interconnected world. From ancient bartering systems to today’s complex digital economies, humanity has constantly experimented with different ways to manage its resources. This article will take you on a fascinating journey through the evolution of global economic models, breaking down complex ideas into easy-to-understand concepts for beginners.

What is an Economic Model, Anyway?

Before we dive in, let’s simplify. Imagine a family deciding how to share chores, manage money, and buy food. Their unspoken rules and habits form their "economic model." On a global scale, it’s the same, but much bigger!

An economic model answers fundamental questions like:

- What goods and services will be produced?

- How will they be produced (e.g., by individuals, companies, or the government)?

- For whom will they be produced (who gets to consume them)?

- How will resources (like land, labor, and capital) be allocated?

Over centuries, these answers have changed dramatically, shaping civilizations, causing conflicts, and driving innovation.

1. The Early Beginnings: Barter, Subsistence, and Feudalism (Pre-16th Century)

For most of human history, economic activity was simple and localized.

- Barter Systems: Before money, people traded goods and services directly. A farmer might swap wheat for a carpenter’s services or a hunter’s furs. This worked for small communities but was inefficient for large-scale trade.

- Subsistence Economies: Most societies were based on subsistence, meaning people produced just enough to meet their basic needs (food, shelter, clothing). There was little surplus, and trade was limited.

- Feudalism: In medieval Europe, feudalism became a dominant economic and social system.

- Land as Wealth: Land was the primary source of wealth and power.

- Hierarchical Structure: Lords owned the land, knights protected it, and serfs (peasants) worked the land in exchange for protection and a small share of the harvest.

- Limited Trade: Most goods were produced locally, and long-distance trade was risky and uncommon.

- Key Takeaway: These early models were characterized by self-sufficiency, limited trade, and rigid social structures. Wealth was primarily tied to land and labor, not financial capital.

2. The Rise of Mercantilism: Nations Accumulating Wealth (16th – 18th Century)

As nation-states began to form and exploration opened up new trade routes, a new economic philosophy emerged: Mercantilism. This was arguably the first truly "global" economic model, driven by the desire of European powers to become rich and powerful.

Core Principles of Mercantilism:

- Wealth is Finite: Mercantilists believed there was a fixed amount of wealth in the world, typically measured in gold and silver.

- National Accumulation: The goal of a nation was to accumulate as much of this wealth as possible.

- Export More, Import Less: To gain gold and silver, a country needed to export more goods than it imported, creating a "trade surplus."

- Colonialism: Colonies were vital. They provided cheap raw materials (like timber, cotton, spices) to the "mother country" and served as captive markets for manufactured goods.

- Government Control: Governments heavily regulated trade, imposed tariffs (taxes on imports), and granted monopolies to favored companies to achieve national economic goals.

- Example: Great Britain’s control over its American colonies, forcing them to sell raw materials only to Britain and buy finished goods from Britain.

Impact: Mercantilism fueled exploration, colonization, and often, conflicts between nations competing for resources and trade routes. It laid the groundwork for global trade but was inherently protectionist and often exploitative.

3. The Classical Economics Revolution: Laissez-Faire & The Invisible Hand (Late 18th – 19th Century)

The inefficiencies and restrictions of Mercantilism eventually led to a powerful counter-movement: Classical Economics, spearheaded by the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith. His 1776 book, "The Wealth of Nations," is considered the foundation of modern economics.

Key Ideas of Classical Economics:

- Laissez-Faire (Let Do): Smith argued that governments should interfere as little as possible in the economy. "Laissez-faire" means "let do" or "let go" in French.

- The Invisible Hand: Smith’s most famous concept. He proposed that individuals, pursuing their own self-interest in a free market, unintentionally benefit society as a whole. It’s like an "invisible hand" guides resources to where they are most needed.

- Free Trade: Instead of hoarding gold, nations should specialize in producing what they do best and trade freely with others. This leads to greater overall wealth for everyone.

- Division of Labor: Breaking down production into specialized tasks makes workers more efficient and lowers costs.

- Supply and Demand: Prices and quantities of goods are determined naturally by the interaction of buyers and sellers.

- Impact: This model championed free markets, individual liberty, and limited government. It fueled the Industrial Revolution, leading to unprecedented economic growth and innovation. However, it also led to significant wealth inequality and poor working conditions in early factories, as there were few regulations to protect workers or the environment.

4. The Keynesian Revolution: Government Intervention (Mid-20th Century)

The early 20th century saw massive economic upheavals, most notably the Great Depression (1929-1939). Classical economics, with its belief in self-correcting markets, struggled to explain or fix such a prolonged downturn. This paved the way for the ideas of British economist John Maynard Keynes.

Core Tenets of Keynesian Economics:

- Market Failure: Keynes argued that free markets don’t always self-correct quickly, especially during severe recessions or depressions. They can get stuck in a rut of low demand and high unemployment.

- Government Role: He proposed that governments have a crucial role to play in stabilizing the economy.

- Demand-Side Economics: When the economy slows down, the government should increase its spending (e.g., on infrastructure projects, unemployment benefits) or cut taxes to boost "aggregate demand" (total spending in the economy). This stimulates production and job creation.

- Fiscal Policy: Using government spending and taxation to influence the economy.

- Monetary Policy: Central banks using interest rates and money supply to influence the economy (Keynes influenced this, though it developed further).

- Impact: Keynesian ideas became dominant in many Western economies after World War II, leading to the "Golden Age of Capitalism" (1950s-1970s) characterized by stable growth, low unemployment, and the development of welfare states (government-provided social safety nets).

5. The Age of Neoliberalism: Return to the Market (Late 20th Century)

By the 1970s, many Western economies faced "stagflation" – a puzzling combination of high inflation and high unemployment. Keynesian policies seemed less effective. This led to a resurgence of ideas emphasizing free markets and limited government, often called Neoliberalism. Influential figures included economists Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek.

Key Principles of Neoliberalism:

- Deregulation: Reducing government rules and regulations on businesses and industries.

- Privatization: Selling state-owned enterprises (like utility companies or airlines) to private companies.

- Free Trade: Further opening up international markets by reducing tariffs and trade barriers.

- Reduced Government Spending: Cutting social welfare programs and other public expenditures to reduce government debt and promote efficiency.

- Monetarism: A strong belief in controlling the money supply as the primary way to manage inflation.

- Individual Responsibility: Emphasizing individual choice and responsibility over collective welfare.

- Prominent Leaders: Policies inspired by neoliberalism were famously implemented by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the UK and President Ronald Reagan in the US during the 1980s.

- Impact: Neoliberal policies led to significant economic restructuring, increased global trade, and often, higher corporate profits. However, critics argue they also contributed to rising income inequality, financial instability, and reduced social safety nets in many countries.

6. Globalization and Interconnectedness (Late 20th – Early 21st Century)

While not a distinct economic model in itself, globalization is a defining feature of the world economy that has profoundly shaped how economic models operate. It refers to the increasing interconnectedness and interdependence of countries through the flow of goods, services, capital, technology, and information.

Drivers of Globalization:

- Technological Advancements: The internet, faster shipping, and cheaper communication made it easier and faster to do business across borders.

- Reduced Trade Barriers: International agreements (like the creation of the World Trade Organization, WTO) aimed to lower tariffs and quotas.

- Rise of Multinational Corporations: Companies operating in many countries, optimizing supply chains globally.

- Increased Capital Flows: Money moving freely across borders for investment.

Impact of Globalization:

- Increased Efficiency and Lower Costs: Companies can produce goods where labor is cheapest, leading to lower prices for consumers.

- Spread of Innovation: Ideas and technologies can spread rapidly around the world.

- Emergence of New Economic Powers: Countries like China and India integrated into the global economy and experienced rapid growth.

- Challenges: Increased competition for domestic industries, job losses in some sectors, exploitation of labor in developing countries, environmental concerns, and vulnerability to global economic shocks (e.g., financial crises spreading rapidly).

7. Modern Challenges & Emerging Models (21st Century and Beyond)

Today, the dominant global economic model is largely a mix of market capitalism (influenced by classical and neoliberal ideas) with varying degrees of government intervention (a nod to Keynesianism). However, this model faces unprecedented challenges, prompting discussions about new approaches.

Key Challenges:

- Rising Inequality: The gap between the rich and poor has widened in many countries.

- Climate Change and Environmental Degradation: The current model’s reliance on endless growth and consumption is unsustainable.

- Technological Disruption: Automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and the digital economy are changing the nature of work and value creation.

- Financial Crises: The interconnectedness of global markets means a crisis in one region can quickly spread worldwide.

- Geopolitical Shifts: Trade wars, nationalism, and pandemics highlight the vulnerabilities of global supply chains.

- Aging Populations: Many developed countries face challenges with fewer workers supporting a growing number of retirees.

Emerging Ideas and Discussions for Future Models:

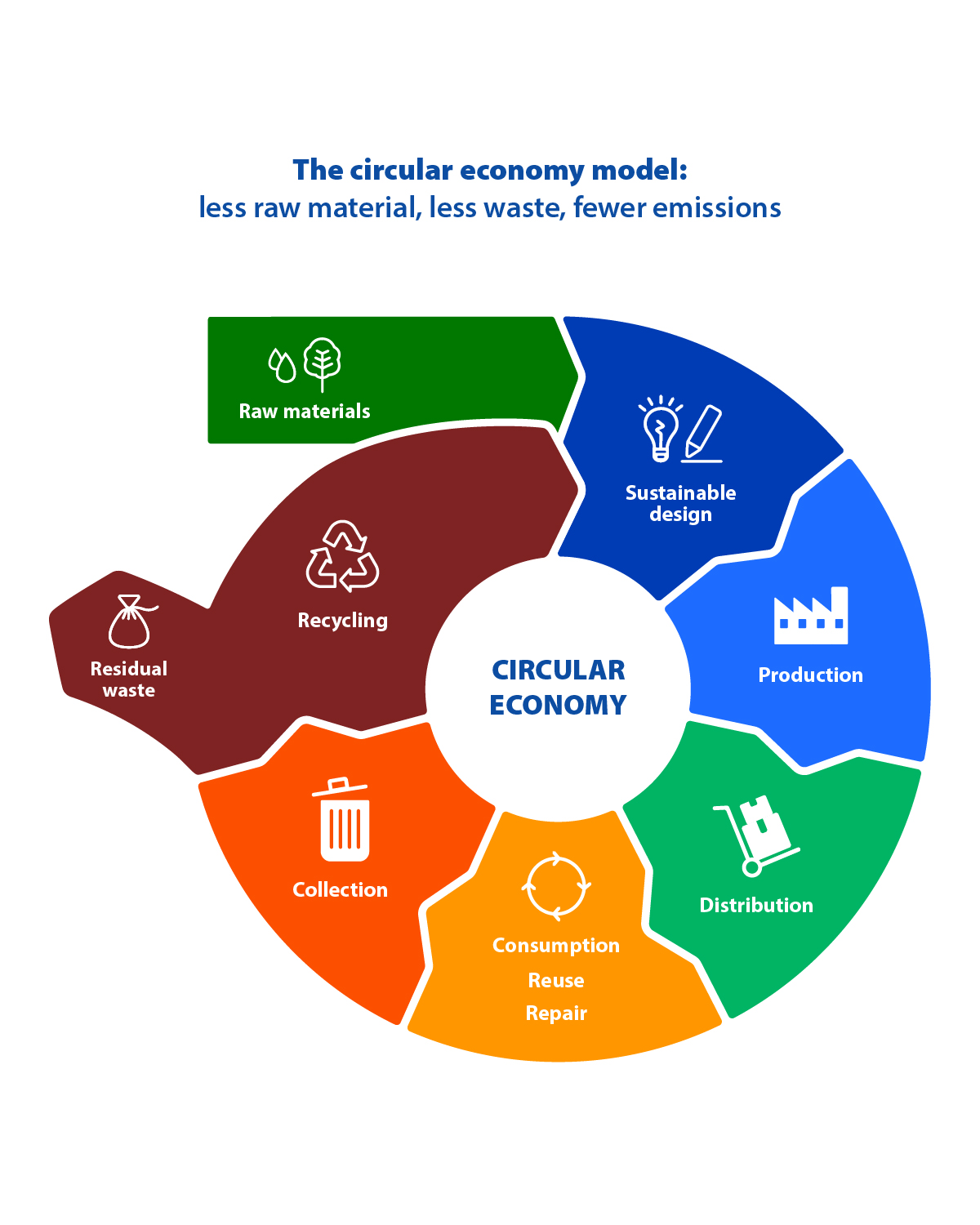

- Sustainable and Green Economies: Shifting to renewable energy, circular economy principles (reduce, reuse, recycle), and valuing natural capital.

- Inclusive Capitalism/Stakeholder Capitalism: Moving beyond just maximizing shareholder profit to considering the well-being of employees, customers, communities, and the environment.

- Universal Basic Income (UBI): Providing a regular, unconditional income to all citizens, often discussed as a response to automation and job displacement.

- Deglobalization/Reshoring: A potential shift away from highly integrated global supply chains towards more localized production, driven by resilience and national security concerns.

- Digital Economy Governance: Developing new rules and regulations for data, AI, and platform monopolies.

- Social Market Economy: A model (common in parts of Europe) that combines elements of free markets with strong social welfare provisions and worker protections.

Conclusion: An Ever-Evolving Story

The evolution of global economic models is a continuous story of human adaptation, innovation, and sometimes, struggle. From the localized simplicity of barter to the complex interconnectedness of today’s digital world, each model has emerged as a response to the challenges and opportunities of its time.

There’s no single "perfect" economic model. Each has its strengths and weaknesses, creating wealth for some while leaving others behind. As we face the unique challenges of the 21st century – from climate change to technological disruption and persistent inequality – societies around the world will continue to experiment, adapt, and redefine how we organize our economic lives. Understanding this ongoing evolution is the first step towards participating in the conversation about shaping the economic future we want to build.

Post Comment