Understanding Liquidity Crises in Financial Markets: A Beginner’s Guide

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you needed cash urgently, but all your money was tied up in assets you couldn’t sell quickly, like a house or a car? That feeling of being "cash-poor" but "asset-rich" is a simple, relatable way to understand the core concept of a liquidity crisis in the vast and complex world of financial markets.

A liquidity crisis isn’t just a hiccup; it’s a severe disruption that can send shockwaves through economies, affecting everything from global banks to your local businesses. For beginners, the terminology can seem daunting, but breaking it down reveals a fascinating and crucial aspect of how our financial system works – and sometimes, falters.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll demystify liquidity crises, explaining what they are, why they happen, their devastating effects, and what measures are taken to prevent and mitigate them.

1. What Exactly is "Liquidity"? The Foundation of Finance

Before we dive into a crisis, let’s understand what "liquidity" means in finance. Think of it as how easily and quickly an asset can be converted into cash without losing significant value.

- Highly Liquid Assets:

- Cash: The most liquid asset.

- Checking account balances: Easily accessible.

- Stocks of major companies: Can usually be sold quickly on an exchange.

- Government bonds (especially short-term): Very easy to sell.

- Illiquid Assets:

- Real Estate (houses, land): Takes time, effort, and often price concessions to sell.

- Private company shares: Hard to find buyers quickly.

- Art or collectibles: Niche market, slow sales process.

Why is Liquidity Important?

Imagine a world without readily available cash or easy ways to sell assets. Transactions would grind to a halt. In financial markets, liquidity is the grease that keeps the gears turning.

- Facilitates Transactions: Buyers can find sellers, and vice versa, quickly and at fair prices.

- Reduces Risk: Investors know they can exit their positions if needed.

- Promotes Confidence: When markets are liquid, participants trust that they can manage their money effectively.

- Supports Economic Growth: Businesses can access financing, and consumers can make purchases, knowing their assets are convertible.

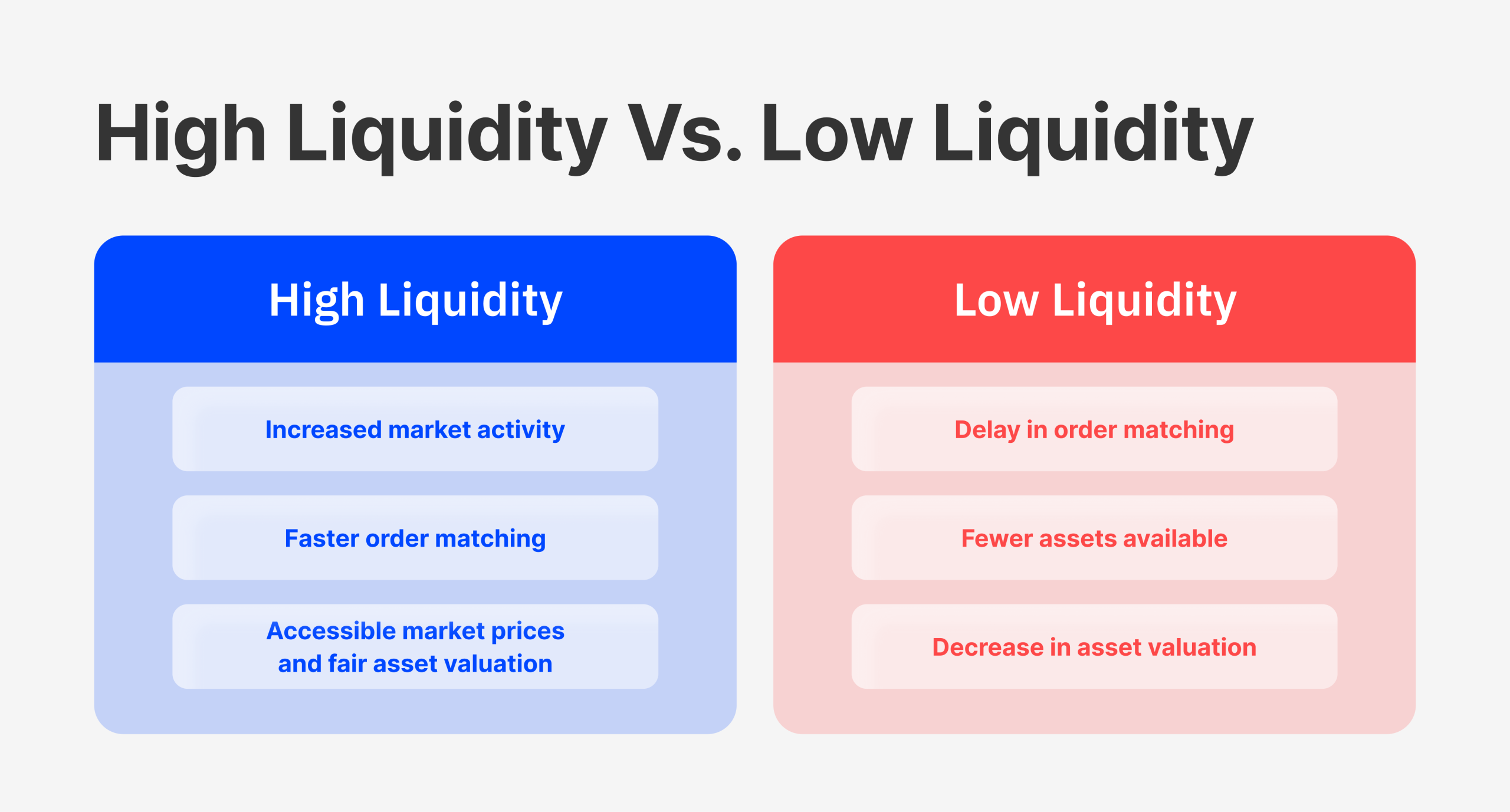

Two Key Types of Liquidity:

- Market Liquidity: This refers to how easily an asset can be bought or sold in the market without its price being significantly affected. A deep market with many buyers and sellers usually indicates high market liquidity.

- Funding Liquidity: This is about a firm’s (like a bank’s) ability to meet its short-term cash obligations. Do they have enough cash or easily convertible assets to pay their bills, meet withdrawal requests, and cover their debts?

Both types of liquidity are interconnected and vital for a healthy financial system.

2. What is a Liquidity Crisis? When the Well Runs Dry

A liquidity crisis occurs when there isn’t enough readily available cash or easily convertible assets in the financial system to meet demand. It’s like everyone suddenly needs to withdraw their money from the bank, but the bank doesn’t have enough physical cash on hand, even though it has plenty of assets (like loans to others).

Key Characteristics of a Liquidity Crisis:

- Loss of Confidence: This is often the spark. Investors, banks, and businesses lose faith in each other’s ability to pay debts or survive, leading them to hoard cash.

- Frozen Markets: It becomes difficult or impossible to buy or sell certain assets, even if they were previously liquid. Buyers disappear, and sellers are forced to drastically cut prices.

- Credit Crunch: Banks become unwilling to lend to each other or to businesses, fearing they won’t get their money back. This starves the economy of vital credit.

- "Fire Sale" Dynamics: To raise cash, institutions are forced to sell assets quickly, often at much lower prices than their true value. This further depresses asset prices, creating a vicious cycle.

- Contagion (Domino Effect): The problem spreads from one institution or market to another, much like a contagious disease.

Imagine a chain of dominoes: one falls, hitting the next, and soon a whole row is down. In a liquidity crisis, one financial institution’s inability to meet its obligations can cause others to panic, leading them to pull back funding or sell assets, which then hurts the next institution, and so on.

3. Common Causes of Liquidity Crises

Liquidity crises don’t just happen out of the blue. They typically arise from a combination of underlying vulnerabilities and specific triggers.

-

A. Loss of Confidence and Fear (The Core Problem):

- This is the most potent driver. If people fear an institution (like a bank) might fail, they’ll rush to withdraw their money. If they fear an asset’s value will plummet, they’ll rush to sell. This collective fear quickly depletes available cash.

- Example: A "bank run" – where many depositors try to withdraw their money at once, exceeding the bank’s available cash reserves.

-

B. Asset-Liability Mismatches:

- Financial institutions, especially banks, often borrow short-term (e.g., from depositors who can withdraw money anytime) and lend long-term (e.g., mortgages that are paid back over decades).

- If short-term funding dries up, they can’t meet their obligations, even if their long-term loans are performing well. They are "liquid" on the asset side but "illiquid" on the liability side.

-

C. Excessive Leverage:

- Leverage means borrowing money to amplify returns. While it can boost profits in good times, it magnifies losses in bad times.

- If asset values fall, leveraged institutions quickly become insolvent (debts exceed assets) and are forced to sell assets to cover their loans, adding to the "fire sale" pressure.

-

D. Bursting Asset Bubbles:

- An "asset bubble" occurs when the price of an asset (like housing or tech stocks) rises rapidly and unsustainably, far exceeding its intrinsic value.

- When the bubble bursts, prices crash. This can wipe out vast amounts of wealth, making it impossible for many to repay their loans or for institutions holding these assets to remain solvent, triggering a liquidity crunch.

-

E. Interconnectedness of the Financial System:

- Modern financial markets are highly interconnected globally. Banks lend to other banks, companies issue bonds that are bought by investment funds, and derivatives link different parts of the system.

- A problem in one corner of the market can quickly spread through these links, causing widespread distress.

-

F. Sudden, Unexpected Shocks (Black Swans):

- Events like natural disasters, terrorist attacks, or global pandemics (like COVID-19) can trigger sudden risk aversion and a flight to safety, causing investors to hoard cash and markets to seize up. These events are often impossible to predict.

4. The Domino Effect: How a Crisis Spreads and Impacts Everyone

A liquidity crisis rarely stays confined to one institution. Here’s a simplified chain reaction:

- Initial Spark: A bank, investment fund, or large company faces a funding shortage or a significant loss on its investments.

- Loss of Trust: Other financial institutions, fearing this entity might default, stop lending to it or demand immediate repayment of loans.

- Panic Spreads: This fear extends to other seemingly healthy institutions. Banks become wary of lending to any other bank, leading to a freeze in the interbank lending market (where banks lend to each other).

- Asset Fire Sales: To raise cash, institutions are forced to sell assets quickly. This floods the market, driving down asset prices further.

- Margin Calls: As asset values fall, institutions that borrowed against these assets face "margin calls," meaning they must put up more cash or sell more assets to cover their loans. This intensifies the fire sale.

- Credit Crunch: With banks hoarding cash and unwilling to lend, businesses and individuals find it impossible to get loans for expansion, investments, or even daily operations.

- Economic Slowdown: Without access to credit, businesses cut back on production, lay off workers, and halt investments. Consumers reduce spending. This leads to a recession or even a depression.

- Real-World Impact: Jobs are lost, bankruptcies rise, and the general standard of living declines.

5. Real-World Examples of Liquidity Crises

Understanding these crises through historical examples helps solidify the concepts.

-

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC):

- Cause: A bubble in the U.S. housing market fueled by subprime mortgages (loans to borrowers with poor credit). When the bubble burst, mortgage-backed securities (complex financial products based on these loans) lost massive value.

- Liquidity Aspect: Banks and financial institutions that held these securities became highly illiquid. They couldn’t sell these assets, and other banks stopped lending to them, fearing their own exposure. This led to the collapse of institutions like Lehman Brothers and a freeze in global credit markets.

- Impact: A severe global recession, government bailouts, and lasting changes to financial regulation.

-

The Asian Financial Crisis (1997-1998):

- Cause: Rapid capital inflows into Asian economies, leading to asset bubbles and excessive borrowing in foreign currencies. When investor confidence waned, capital fled quickly.

- Liquidity Aspect: Countries like Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea saw their currencies collapse as foreign investors pulled out their money. Their banks and companies, having borrowed heavily in U.S. dollars, found themselves unable to repay these debts with devalued local currencies, leading to widespread illiquidity and corporate defaults.

- Impact: Significant economic contraction, social unrest, and a reassessment of international capital flows.

-

The COVID-19 Market Turmoil (March 2020):

- Cause: A sudden, external shock from the global pandemic and associated lockdowns.

- Liquidity Aspect: As businesses shut down and uncertainty soared, investors worldwide rushed to sell almost everything – stocks, bonds, even gold – to hold cash. This created an unprecedented demand for U.S. dollars and threatened to freeze critical parts of the financial system.

- Impact: Central banks and governments had to intervene swiftly and massively (more on this below) to inject liquidity and prevent a full-blown financial collapse, demonstrating the fragility of the system even to non-financial shocks.

6. Who Gets Hit Hardest?

While liquidity crises affect everyone, some bear the brunt more directly:

- Financial Institutions (Banks, Investment Firms): They are at the heart of the system and are the first to experience funding shortfalls and asset value declines.

- Businesses: Small and large businesses alike rely on credit for operations, payroll, and expansion. A credit crunch starves them of vital capital, leading to layoffs and bankruptcies.

- Individuals:

- Job Losses: As businesses contract, unemployment rises.

- Loss of Savings/Investments: Stock market crashes can wipe out retirement savings.

- Difficulty Accessing Credit: Mortgages, car loans, and business loans become harder to get or more expensive.

- Reduced Spending Power: Economic downturns lead to less disposable income.

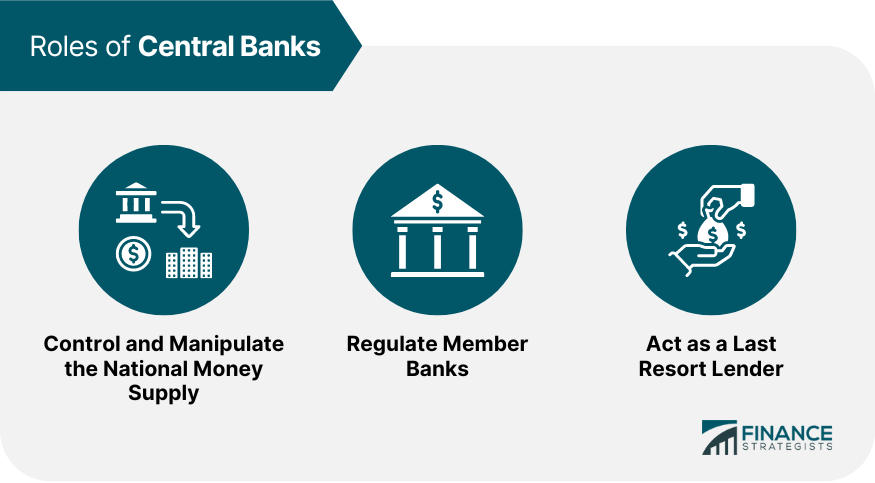

7. The Role of Central Banks and Governments: The "Lenders of Last Resort"

When a liquidity crisis hits, governments and central banks (like the Federal Reserve in the U.S. or the European Central Bank) are the primary responders. They act as the ultimate safety net for the financial system.

-

A. Lender of Last Resort:

- This is a central bank’s most crucial role during a crisis. If banks can’t borrow from each other, the central bank steps in to lend them money (often against collateral). This ensures banks have enough cash to meet withdrawals and obligations, preventing widespread failures and panic.

-

B. Interest Rate Adjustments:

- Central banks can drastically cut interest rates to make borrowing cheaper and encourage lending and economic activity.

-

C. Quantitative Easing (QE):

- During severe crises, central banks might buy large quantities of government bonds and other financial assets from banks. This injects massive amounts of cash directly into the financial system, boosting liquidity and lowering long-term interest rates.

-

D. Bailouts and Guarantees:

- Governments may step in to directly inject capital into struggling financial institutions (a "bailout") or guarantee their debts to restore confidence and prevent their collapse. This is controversial but often deemed necessary to prevent systemic collapse.

-

E. Regulatory Reforms:

- After a crisis, governments and regulators often implement new rules to make the financial system more resilient. Examples include:

- Higher Capital Requirements: Banks must hold more of their own funds, reducing their reliance on borrowed money.

- Stress Tests: Banks are regularly tested to see if they can withstand severe economic downturns.

- New Oversight Bodies: Agencies are created or strengthened to monitor financial risks.

- After a crisis, governments and regulators often implement new rules to make the financial system more resilient. Examples include:

8. Preventing Future Crises: Building a More Resilient System

While completely preventing financial crises is likely impossible, significant efforts are made to reduce their frequency and severity.

- Stronger Regulation and Oversight:

- Implementing and enforcing stricter rules for banks and other financial institutions to limit excessive risk-taking and leverage.

- Macroprudential Policies:

- These policies aim to protect the financial system as a whole, rather than just individual firms. Examples include limiting mortgage lending when housing prices are booming or increasing capital requirements during periods of high credit growth.

- Enhanced International Cooperation:

- Given the global nature of finance, countries work together to share information, coordinate policies, and develop common standards to address cross-border risks.

- Early Warning Systems:

- Regulators and central banks constantly monitor financial markets for signs of stress, such as unusual spikes in certain asset prices or strains in lending markets.

- Better Data Collection and Analysis:

- Understanding the complex interconnections within the financial system requires robust data to identify vulnerabilities before they become critical.

Conclusion: Understanding is the First Step

Liquidity crises are complex, but their core principles – the flow of money, trust, and the ability to convert assets into cash – are understandable. They serve as stark reminders of the interconnectedness of our global financial system and the critical role that central banks and governments play in maintaining stability.

For beginners, grasping these concepts is more than just academic; it’s about understanding the forces that shape our economies, influence our jobs, and impact our financial well-being. By understanding the dynamics of liquidity and its potential crises, we are better equipped to navigate the financial world and appreciate the ongoing efforts to build a more secure and resilient future.

Post Comment