Understanding EBITDA: A Key Metric for Investors

Navigating the world of financial statements can often feel like deciphering a complex code. With a myriad of acronyms and metrics, it’s easy for even seasoned investors to get lost. However, understanding a few core concepts can significantly empower your investment decisions. One such crucial metric, widely used across industries, is EBITDA.

For investors, EBITDA isn’t just another financial term; it’s a powerful lens through which to evaluate a company’s core operational health and potential. This comprehensive guide will demystify EBITDA, explaining what it is, why it matters, how it’s used, and its important limitations. By the end, you’ll be equipped to use EBITDA as a valuable tool in your investment analysis toolkit.

What is EBITDA? Breaking Down the Acronym

Let’s start with the basics. EBITDA stands for:

- Earnings

- Before

- Interest

- Taxes

- Depreciation

- Amortization

In simple terms, EBITDA represents a company’s profitability from its core operations before accounting for certain non-operating expenses and non-cash charges. Think of it as looking at the raw earning power of a business, stripped of factors that might obscure its true operational efficiency.

Let’s break down each component:

- Earnings: This is the starting point, typically the company’s net income or operating income.

- Before Interest: Interest expenses relate to a company’s debt. By adding this back, EBITDA aims to show profitability regardless of how a company is financed (i.e., how much debt it carries). This makes it easier to compare companies with different debt structures.

- Before Taxes: Taxes are government-imposed levies that can vary significantly based on location, tax laws, and specific company deductions. Excluding taxes allows for a cleaner comparison of operational performance across different tax jurisdictions or over time as tax laws change.

- Before Depreciation: Depreciation is an accounting method that spreads the cost of a tangible asset (like machinery, buildings, or vehicles) over its useful life. It’s a non-cash expense, meaning no actual money leaves the company’s bank account when depreciation is recorded.

- Before Amortization: Similar to depreciation, amortization is a non-cash expense that spreads the cost of an intangible asset (like patents, copyrights, or goodwill) over its useful life. Again, no cash changes hands when amortization is recorded.

The Big Idea: By excluding interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, EBITDA attempts to give investors a clearer picture of how much profit a company generates from its actual business activities, without the influence of financing decisions, tax strategies, or large non-cash accounting entries related to past investments.

Why is EBITDA Important for Investors? The "So What?" Factor

As an investor, you’re looking for companies that can consistently generate profits. EBITDA offers a unique perspective that can be incredibly insightful:

-

Focus on Core Operational Performance:

- EBITDA highlights how efficiently a company runs its main business. It strips away the effects of financing (interest) and government policies (taxes), which are often outside the day-to-day operational control of management.

- It also removes the impact of past investment decisions (depreciation and amortization), which can sometimes mask current operational strength.

-

Facilitates Cross-Company Comparisons:

- Imagine comparing a highly leveraged (debt-heavy) company to one that’s debt-free, or a company operating in a high-tax country versus one in a tax haven. Their net incomes might look vastly different, even if their core businesses are equally efficient.

- EBITDA levels the playing field, allowing investors to compare the operational profitability of companies regardless of their capital structure, tax situation, or significant past investments in assets. This is especially useful for comparing companies within the same industry.

-

Highlights Potential for Cash Flow:

- While not a direct measure of cash flow, EBITDA is often seen as a proxy for a company’s ability to generate cash from its operations. Since depreciation and amortization are non-cash expenses, adding them back to earnings helps bring us closer to the cash generated before debt payments and taxes.

- This is particularly valuable for capital-intensive industries (like manufacturing or telecommunications) where large depreciation charges can significantly reduce reported net income, even if the business is generating substantial cash.

-

Valuation Tool:

- EBITDA is frequently used in valuation multiples, most notably the Enterprise Value to EBITDA (EV/EBITDA) ratio.

- Enterprise Value (EV) represents the total value of a company, including its market capitalization, debt, and minority interest, minus cash and cash equivalents.

- EV/EBITDA is popular because it offers a "capital structure neutral" valuation metric, meaning it’s less affected by a company’s debt levels than price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios. This makes it useful for comparing companies with different financing structures.

-

Useful in Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A):

- In M&A deals, buyers often look at a target company’s EBITDA to quickly assess its earning potential and to determine a fair purchase price. It provides a common language for evaluating businesses regardless of their specific accounting policies or financing.

How to Calculate EBITDA (Simplified)

While you’ll often find EBITDA directly reported in a company’s financial statements (especially non-GAAP reporting), it’s useful to understand how it’s derived.

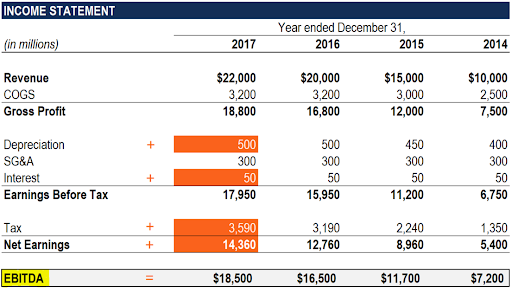

The most common way to calculate EBITDA is to start with Net Income and add back the excluded items:

EBITDA = Net Income + Interest Expense + Tax Expense + Depreciation + Amortization

Alternatively, you can start from Operating Income (EBIT), which is already before interest and taxes:

EBITDA = Operating Income (EBIT) + Depreciation + Amortization

Where to Find the Numbers:

- Net Income, Interest Expense, Tax Expense: All can be found on a company’s Income Statement.

- Depreciation and Amortization: These are typically found on the Income Statement (often combined with other operating expenses or listed separately) or explicitly detailed in the Cash Flow Statement (in the operating activities section, as they are non-cash adjustments to net income).

EBITDA vs. Other Profitability Metrics: A Quick Comparison

It’s important to understand how EBITDA fits into the broader picture of profitability:

-

Net Income (The "Bottom Line"): This is a company’s profit after all expenses, including interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. It’s the most comprehensive measure of profit and is often what investors focus on for dividends and overall financial health.

- Why EBITDA is different: EBITDA focuses solely on operational earnings before these specific deductions.

-

Gross Profit: Revenue minus the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). It shows how much profit a company makes directly from selling its products or services, before operating expenses.

- Why EBITDA is different: EBITDA goes deeper, considering operating expenses but excluding the non-operational and non-cash items.

-

Operating Income (EBIT – Earnings Before Interest & Taxes): This shows a company’s profit from its core operations after deducting operating expenses (like salaries, rent, marketing, and depreciation/amortization), but before interest and taxes.

- Why EBITDA is different: EBITDA adds back depreciation and amortization to EBIT, aiming for an even purer view of cash-generating operational efficiency, especially for capital-intensive businesses.

Think of it like peeling an onion:

- Gross Profit is the outer layer, showing profitability from sales.

- Operating Income (EBIT) is the next layer, showing profitability from core operations after typical running costs.

- EBITDA is even closer to the core, showing operational profitability before non-cash charges and financing/tax decisions.

- Net Income is the very center, representing the final profit available to shareholders after all expenses are accounted for.

The Pros: Advantages of Using EBITDA

When used correctly, EBITDA offers several powerful advantages for investors:

- Clearer View of Operational Performance: It strips away variables that can distort profitability, allowing you to see how well the core business is truly performing.

- Enhanced Comparability: Makes it easier to compare companies in the same industry, regardless of their debt levels, tax structures, or how old their assets are. This is particularly valuable for global comparisons.

- Good for Asset-Heavy Industries: Companies with significant fixed assets (e.g., manufacturing, airlines, real estate) often have high depreciation expenses, which can suppress net income. EBITDA provides a better measure of their operational cash-generating ability.

- Useful for Highly Leveraged Companies: When a company carries a lot of debt, its interest expenses can be very high, drastically reducing net income. EBITDA allows you to see the operational strength before debt servicing costs.

- Highlights Cash Flow Potential (Proxy): By adding back non-cash expenses, EBITDA gives an indication of the cash generated by operations that could potentially be used for debt repayment, capital expenditures, or growth initiatives.

- Standard in M&A and Private Equity: Due to its focus on operational earnings and comparability, EBITDA is a standard metric used in valuing and analyzing companies for acquisition.

The Cons: Limitations and Caveats of EBITDA

Despite its widespread use, EBITDA is not a perfect metric and has significant limitations that investors must be aware of. Using it in isolation can lead to misinformed decisions.

-

Not a GAAP Metric:

- Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) are a set of standardized accounting rules. EBITDA is not defined by GAAP. This means companies have some flexibility in how they calculate and present it, which can lead to inconsistencies.

- Always scrutinize how a company presents its "adjusted EBITDA" and understand what has been added or subtracted.

-

Ignores Capital Expenditures (CAPEX):

- This is perhaps its biggest flaw. Depreciation and amortization are removed, but these expenses reflect the wear and tear on assets that must eventually be replaced or maintained.

- EBITDA doesn’t account for the ongoing capital investments a company needs to make to simply maintain its current level of operations, let alone grow. A company with high EBITDA but also high, necessary CAPEX might not be generating much true free cash flow.

-

Not a True Measure of Cash Flow:

- While it’s a proxy for cash flow, EBITDA is not cash flow from operations. It doesn’t account for changes in working capital (like inventory or accounts receivable/payable) or other non-operating cash flows.

- A company can have high EBITDA but still struggle with cash flow if, for example, its customers aren’t paying on time (increasing accounts receivable).

-

Hides Debt Burden:

- By adding back interest expenses, EBITDA intentionally ignores a company’s debt obligations. A company might have fantastic EBITDA but be drowning in debt, making it highly risky.

- Investors must look at the balance sheet and cash flow statement to understand debt levels and repayment capabilities.

-

Ignores Tax Burden:

- Similarly, by ignoring taxes, EBITDA doesn’t reflect the actual tax payments a company has to make. Taxes are a real outflow of cash and a necessary cost of doing business.

-

Potential for Manipulation:

- Because it’s not GAAP, some companies might use "adjusted EBITDA" to paint a rosier picture of their financial health, excluding certain expenses they deem "non-recurring" or "non-operational." Always be skeptical of overly adjusted numbers.

When to Use EBITDA (And When Not To)

Use EBITDA When:

- Comparing companies in capital-intensive industries: Where depreciation can be a large and distorting factor.

- Analyzing highly leveraged companies: To assess their operational strength before debt service.

- Performing M&A analysis: As a standard metric for valuation and comparison.

- Looking at companies with diverse tax situations: To normalize for different tax rates.

- Evaluating early-stage companies or startups: Which might have significant upfront investments (leading to high D&A) but are starting to show operational profitability.

Do NOT Use EBITDA As:

- A substitute for Net Income: Net income tells you the true profit available to shareholders.

- A measure of free cash flow: You need to consider capital expenditures and changes in working capital for that.

- The only metric for investment decisions: Always use it in conjunction with other financial statements and metrics.

- A way to ignore debt: Always examine a company’s balance sheet and debt covenants.

- An excuse to overlook necessary capital expenditures: Depreciation and amortization reflect real asset decay that will require future cash outlays.

Key Takeaways for Investors

EBITDA is a powerful tool, but like any tool, its effectiveness depends on how well you understand its purpose and limitations.

- EBITDA is an operational profitability metric: It tells you how much money a company makes from its core business activities, before the impact of financing, taxes, and non-cash asset charges.

- It’s great for comparability: Especially across companies with different capital structures, tax environments, or asset bases.

- It’s NOT cash flow: Remember that depreciation and amortization are real costs of using assets that will eventually need to be replaced. Interest and taxes are also real cash outflows.

- Always use it in context: Never rely solely on EBITDA. Always examine the full set of financial statements – the Income Statement, Balance Sheet, and Cash Flow Statement – to get a complete picture of a company’s financial health.

- Beware of "adjusted EBITDA": Scrutinize any adjustments a company makes to its reported EBITDA.

By understanding EBITDA and integrating it thoughtfully into your analysis, you can gain a deeper, more nuanced understanding of a company’s true earning power and make more informed investment decisions. It’s not the silver bullet, but it’s certainly a valuable arrow in your quiver.

Post Comment