Moral Hazard in Economic Crises: Unpacking the Invisible Risk

Economic crises are complex beasts, often leaving a trail of questions about what went wrong and how to prevent future turmoil. While many factors contribute to these downturns – from speculative bubbles to geopolitical events – one subtle yet powerful concept plays a crucial role in amplifying risk and shaping responses: Moral Hazard.

If you’ve ever wondered why governments might bail out large corporations, or why some institutions seem to take excessive risks, understanding moral hazard is key. It’s not about morality in the traditional sense, but about the incentives that drive behavior, especially when the consequences of failure are softened.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll break down moral hazard in the context of economic crises, making it easy for anyone to grasp this vital concept.

What Exactly Is Moral Hazard? An Easy Explanation

At its core, moral hazard occurs when one party takes on more risk because they don’t have to bear the full costs of that risk. It’s like having a safety net that encourages you to jump higher, even if you might fall.

Think of it this way:

- You have full insurance on your new car. You might be less careful about where you park it or how fast you drive, knowing that if something happens, the insurance company will cover most of the damage. Your incentive to be cautious is reduced.

- A friend promises to pay for all your broken dishes. You might be more prone to juggling them or stacking them precariously, knowing the financial burden isn’t yours.

In both examples, the presence of a "safety net" (insurance, a generous friend) changes behavior. The person being protected (you, in the car or with the dishes) has less incentive to act carefully because someone else will absorb the cost of their potential mistakes.

Key characteristics of Moral Hazard:

- Altered Behavior: The protected party changes their actions, often becoming riskier.

- Reduced Incentive for Caution: The potential negative consequences are diluted or shifted.

- Often Involves a "Guarantor" or "Insurer": Someone else (an insurance company, a government, a central bank) is implicitly or explicitly ready to absorb losses.

Moral Hazard in Economic Crises: The "Too Big to Fail" Problem

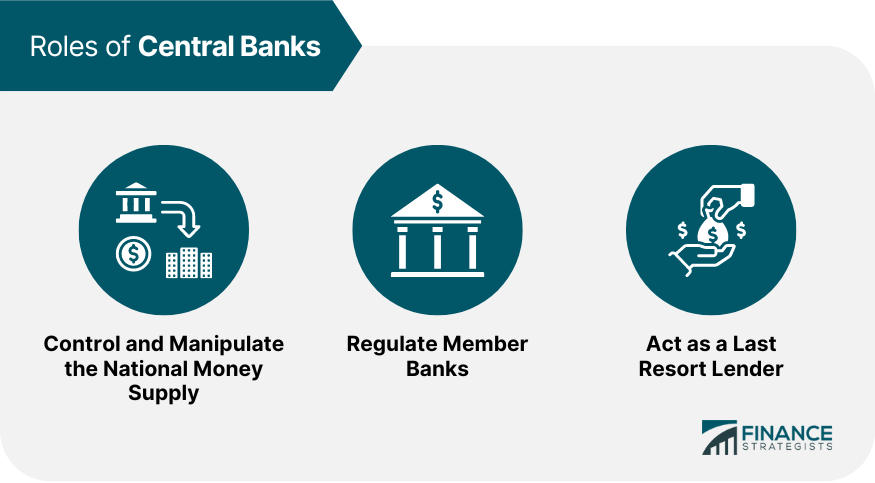

While moral hazard exists in everyday life, its impact becomes truly systemic and dangerous during economic crises, particularly within the financial sector. Here, the "safety net" is often provided by governments or central banks.

The most famous manifestation of moral hazard in this context is the "Too Big to Fail" (TBTF) problem.

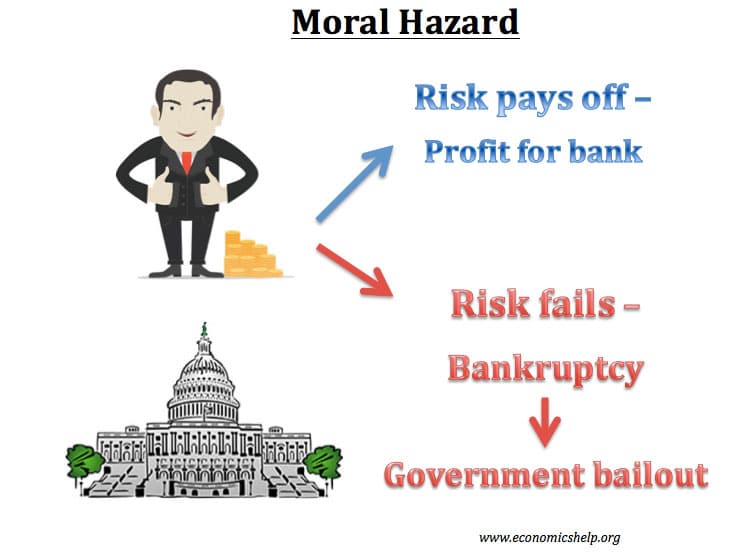

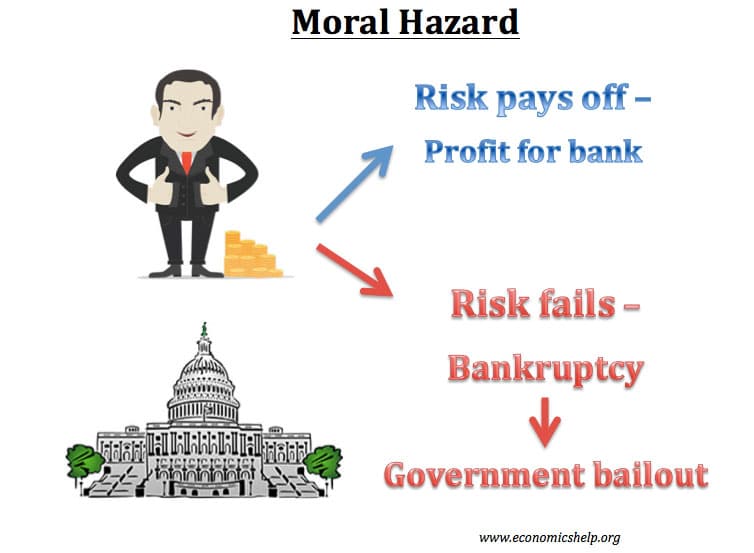

How "Too Big to Fail" Creates Moral Hazard:

- Implicit Guarantee: When a financial institution (like a large bank or insurance company) becomes so massive and interconnected that its failure could trigger a collapse of the entire financial system, governments often feel compelled to step in and prevent its demise. This creates an implicit guarantee – the market believes the government will bail out these institutions if they get into trouble.

- Shifted Risk: Knowing they are likely to be rescued, these "too big to fail" institutions have a powerful incentive to take on excessive risks. They can pursue high-reward, high-risk strategies because they expect to privatize their gains (keep the profits) but socialize their losses (have the government, and thus taxpayers, bear the costs of their failures).

- Distorted Competition: Smaller institutions, which don’t have the TBTF status, can’t take the same level of risk because they face the full consequences of failure. This puts them at a disadvantage and can concentrate even more power in the hands of the largest players.

In essence, the very act of protecting the system from collapse by rescuing large firms can, ironically, encourage those firms to take even greater risks in the future, setting the stage for the next crisis.

Real-World Examples of Moral Hazard in Crises

Let’s look at how moral hazard played out in some recent economic downturns:

1. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis

The 2008 crisis is a textbook example of moral hazard run wild.

- Mortgage Lenders: Many lenders issued "subprime" mortgages to borrowers with poor credit, knowing they could quickly sell these risky loans off to investment banks (a process called securitization). They didn’t bear the full risk if the borrowers defaulted, so they had little incentive to be careful about who they lent to.

- Investment Banks: These banks bought the risky mortgage-backed securities, often using complex financial instruments to amplify their exposure. They believed that if things went south, their sheer size and systemic importance would compel the government to rescue them – which indeed happened with institutions like Bear Stearns and AIG.

- AIG (American International Group): This massive insurance company sold credit default swaps (a form of insurance) on those risky mortgage-backed securities. When the housing market collapsed, AIG faced billions in losses. The U.S. government bailed out AIG with over $180 billion, fearing its collapse would trigger a wider financial meltdown. This rescue reinforced the idea that certain institutions were too big to fail, potentially encouraging future risk-taking by others.

2. Sovereign Debt Crises (e.g., Greece and the Eurozone)

Moral hazard also surfaces in the context of national economies.

- Lenders to Governments: When countries like Greece ran into severe debt problems, there was an expectation among some lenders (banks and investors) that other, stronger Eurozone countries or the European Central Bank (ECB) would step in to prevent a default. This expectation reduced the incentive for lenders to scrutinize Greece’s fiscal health as rigorously as they might have otherwise.

- Governments Themselves: Knowing that their larger European partners might come to their aid, some indebted Eurozone governments might have had less political incentive to implement unpopular austerity measures or structural reforms quickly. The perceived safety net softened the immediate consequences of their fiscal irresponsibility.

The Bailout Dilemma: A Rock and a Hard Place

Understanding moral hazard helps explain the agonizing decisions faced by governments and central banks during a crisis. When a major financial institution is on the brink of collapse, policymakers face a terrible choice:

- Option A: Let it Fail. This upholds market discipline and punishes reckless behavior, potentially reducing future moral hazard. However, it risks catastrophic contagion, leading to widespread job losses, frozen credit markets, and a deep recession.

- Option B: Bail it Out. This prevents immediate systemic collapse and mitigates short-term pain. However, it reinforces the "too big to fail" notion, creating moral hazard and potentially encouraging even riskier behavior in the future, while also burdening taxpayers.

There is no easy answer. The goal is often to find a way to stabilize the system without creating an incentive for future recklessness.

Consequences of Unchecked Moral Hazard

When moral hazard is allowed to run rampant, the results can be devastating for the economy and society:

- Increased Systemic Risk: Financial institutions take on more interconnected and complex risks, making the entire system more fragile and prone to collapse.

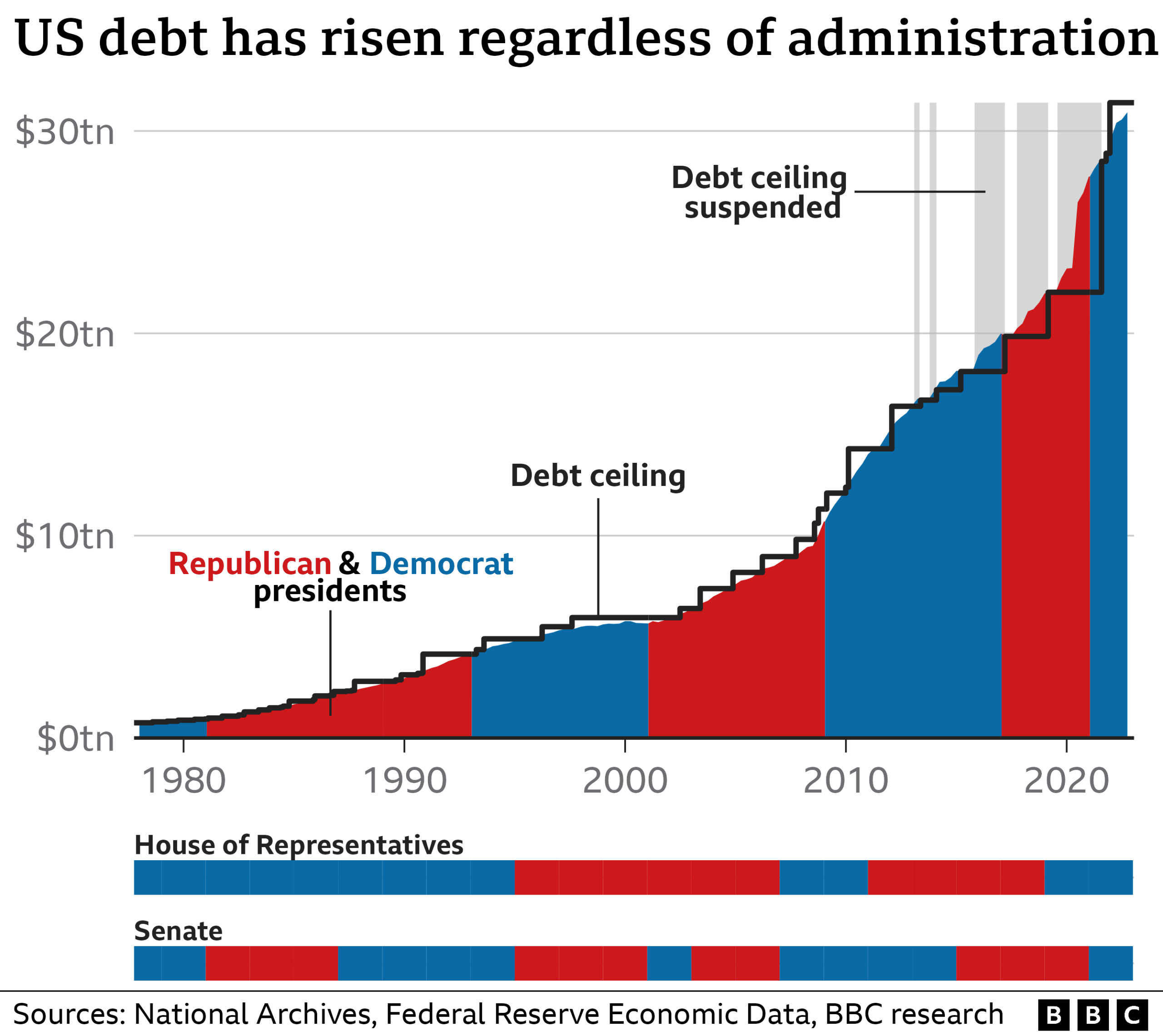

- Higher Costs for Taxpayers: When bailouts occur, the burden of cleaning up financial messes often falls on the public, diverting funds from other critical areas.

- Distorted Market Signals: Risk is mispriced because institutions don’t bear the full cost of their actions, leading to misallocation of capital and unsustainable growth.

- Erosion of Public Trust: Bailouts of large, seemingly irresponsible institutions can fuel public anger and resentment, undermining faith in financial markets and government.

- "Zombie Institutions": Sometimes, bailouts can prop up inefficient or poorly managed firms that should have been allowed to fail, preventing healthier competition and market cleansing.

Mitigating Moral Hazard: Strategies for a Safer System

Policymakers are acutely aware of moral hazard and have implemented various strategies to reduce its impact, though it’s an ongoing challenge:

-

Stricter Regulation and Oversight:

- Increased Capital Requirements: Banks are required to hold more capital (their own money) as a buffer against losses, meaning they have more "skin in the game" before needing a bailout. (e.g., Basel III accords).

- Liquidity Requirements: Rules to ensure banks have enough readily available cash to meet short-term obligations, reducing the risk of sudden collapse.

- Stress Tests: Regular simulations to assess how financial institutions would fare under severe economic downturns, forcing them to prepare for worst-case scenarios.

-

Resolution Authorities and "Bail-ins":

- Orderly Liquidation Authority: Governments are developing mechanisms (like the Dodd-Frank Act in the U.S.) to allow large, failing financial institutions to be wound down in an orderly fashion without resorting to a full taxpayer bailout.

- Bail-ins: Instead of taxpayers bailing out a failing bank, its own creditors (bondholders, and in some cases, large depositors) are forced to take losses. This shifts the burden of failure from the public to those who invested in the institution, increasing their incentive to monitor risk.

-

Executive Compensation Reforms:

- Clawback Provisions: Rules allowing companies to reclaim bonuses or compensation from executives if their actions lead to significant losses or misconduct.

- Long-Term Incentives: Shifting executive pay away from short-term profits towards long-term performance, discouraging excessive risk-taking for immediate gains.

-

Market Discipline:

- Transparency: Requiring financial institutions to disclose more information about their risks and operations allows investors to make more informed decisions and penalize overly risky behavior.

- No Implicit Guarantees: Explicitly stating that certain institutions are not "too big to fail" can help shift market expectations and encourage more cautious lending and investment.

Conclusion: The Enduring Challenge of Moral Hazard

Moral hazard is an intrinsic challenge in any system where risk is shared or mitigated. In the context of economic crises, it highlights the delicate balance between preventing immediate catastrophe and fostering long-term stability. While bailouts might be necessary to avert a deeper collapse, they carry the significant cost of potentially encouraging the very behavior they sought to contain.

Understanding moral hazard empowers us to critically analyze financial policies, question the incentives of powerful institutions, and advocate for regulations that promote responsibility and reduce systemic risk. It’s a reminder that even the most well-intentioned safety nets can have unintended consequences, and the pursuit of a stable financial system requires constant vigilance against the invisible risk of moral hazard.

Post Comment