The Paradox of Thrift: Saving Too Much During a Crisis – When Good Intentions Hurt the Economy

Imagine a severe economic crisis hits. Jobs are uncertain, businesses are struggling, and the future feels incredibly shaky. What’s the natural instinct for most people? To tighten their belts, cut back on spending, and save every penny they can. It sounds like a perfectly sensible, responsible thing to do, right? After all, personal financial prudence is always a good idea.

But what if everyone, or nearly everyone, does this at the same time? What if a collective, well-intentioned effort to save actually makes the economic crisis worse? This is the core idea behind a fascinating and often counter-intuitive economic concept known as The Paradox of Thrift.

In this long-form article, we’ll explore this paradox in detail, breaking down why saving too much during a crisis can be detrimental to the broader economy, using language that’s easy for anyone to understand. We’ll look at its mechanisms, historical examples, and what policymakers try to do to counteract its effects.

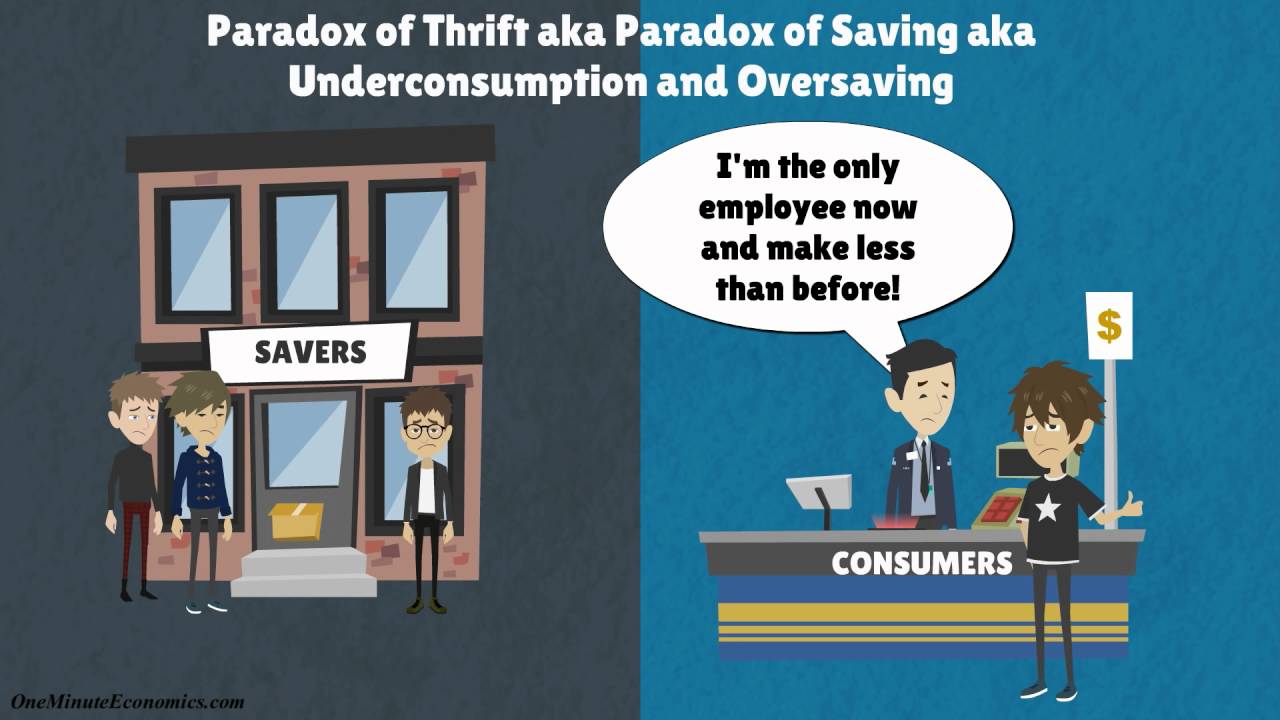

What Exactly is The Paradox of Thrift?

At its heart, the Paradox of Thrift highlights a crucial difference between what’s good for an individual and what’s good for the entire economy (or the "aggregate").

- For an individual: Saving money is wise. It builds an emergency fund, provides for future needs like retirement, and offers a sense of security. If you save more, you become more financially secure.

- For the entire economy (the "aggregate"): If everyone saves more and spends less simultaneously, it can lead to a significant drop in overall demand for goods and services. This widespread reduction in spending can cause a recession to deepen or last longer, making everyone collectively worse off, even those who saved diligently.

Simply put: While individual saving is a virtue, universal saving during a downturn can become a vice for the economy as a whole. It’s a situation where rational individual behavior leads to an irrational and undesirable collective outcome.

Why Do People Save So Much During a Crisis?

The reasons behind increased saving during a crisis are entirely understandable and rooted in basic human psychology and financial common sense:

- Fear and Uncertainty: When the future is unclear (e.g., will I lose my job? Will my investments plummet?), people naturally become more cautious. They hold onto cash as a safety net.

- Job Insecurity: If layoffs are happening or rumored, building up a financial cushion becomes paramount. People fear income loss and want to be prepared.

- Falling Asset Values: In a crisis, the value of stocks, real estate, and other investments might drop. People might feel "poorer" even if their income hasn’t changed, leading them to save more to restore their perceived wealth.

- Lack of Confidence: People might lose trust in banks, financial institutions, or even the government’s ability to fix things. This erosion of confidence drives them to hoard cash.

- Anticipation of Lower Prices (Deflation): If people expect prices to fall further in the future (a phenomenon called deflation, which we’ll discuss), they might delay purchases, hoping to get a better deal later. This waiting game reduces current spending.

How Does Saving Too Much Harm the Economy? The Vicious Cycle

When the collective desire to save overrides the willingness to spend, a dangerous economic chain reaction begins:

-

Reduced Consumer Spending (The First Domino):

- People buy fewer clothes, eat out less, delay buying new cars or appliances, and cancel vacations.

- This reduction in spending directly translates to less money flowing into businesses.

-

Businesses Suffer and Cut Back:

- With fewer customers, businesses experience lower sales and reduced revenue.

- Profits shrink, and some may even operate at a loss.

- To cope, businesses:

- Reduce production: They don’t need to make as many goods if no one is buying them.

- Lay off workers: Fewer sales mean less need for staff, leading to job losses.

- Freeze hiring: No new jobs are created.

- Delay investments: Why buy new machinery or expand facilities if demand is low?

-

Increased Unemployment and Lower Incomes:

- Layoffs mean more people are out of work, and those who remain employed might face wage cuts or reduced hours.

- This leads to even less money in people’s pockets, reinforcing the cycle of reduced spending.

-

The Deflationary Spiral (A Dangerous Outcome):

- With demand so low, businesses might try to attract customers by lowering prices.

- While lower prices sound good, widespread and persistent price drops (deflation) can be very damaging.

- Delayed Purchases: If you expect prices to keep falling, why buy today? You wait, further reducing demand.

- Increased Debt Burden: The real value of debts (mortgages, loans) goes up because the money you earn is worth less, but your debt remains the same. This makes it harder to pay off debts, leading to bankruptcies.

- Reduced Business Profits: Falling prices erode profit margins, making it even harder for businesses to survive, leading to more layoffs.

-

Lack of Business Investment:

- Why would a company invest in new equipment, research, or expansion if consumers aren’t buying, and the future looks bleak?

- This lack of investment hurts long-term economic growth and innovation.

The result: A self-reinforcing downward spiral. People save because they’re worried, but their collective saving causes businesses to suffer, leading to job losses, which makes people even more worried and prone to saving, further worsening the crisis. The economy gets stuck in a rut, unable to recover.

Historical Examples of The Paradox of Thrift in Action

The Paradox of Thrift isn’t just a theoretical concept; it has played out in real-world economic crises:

-

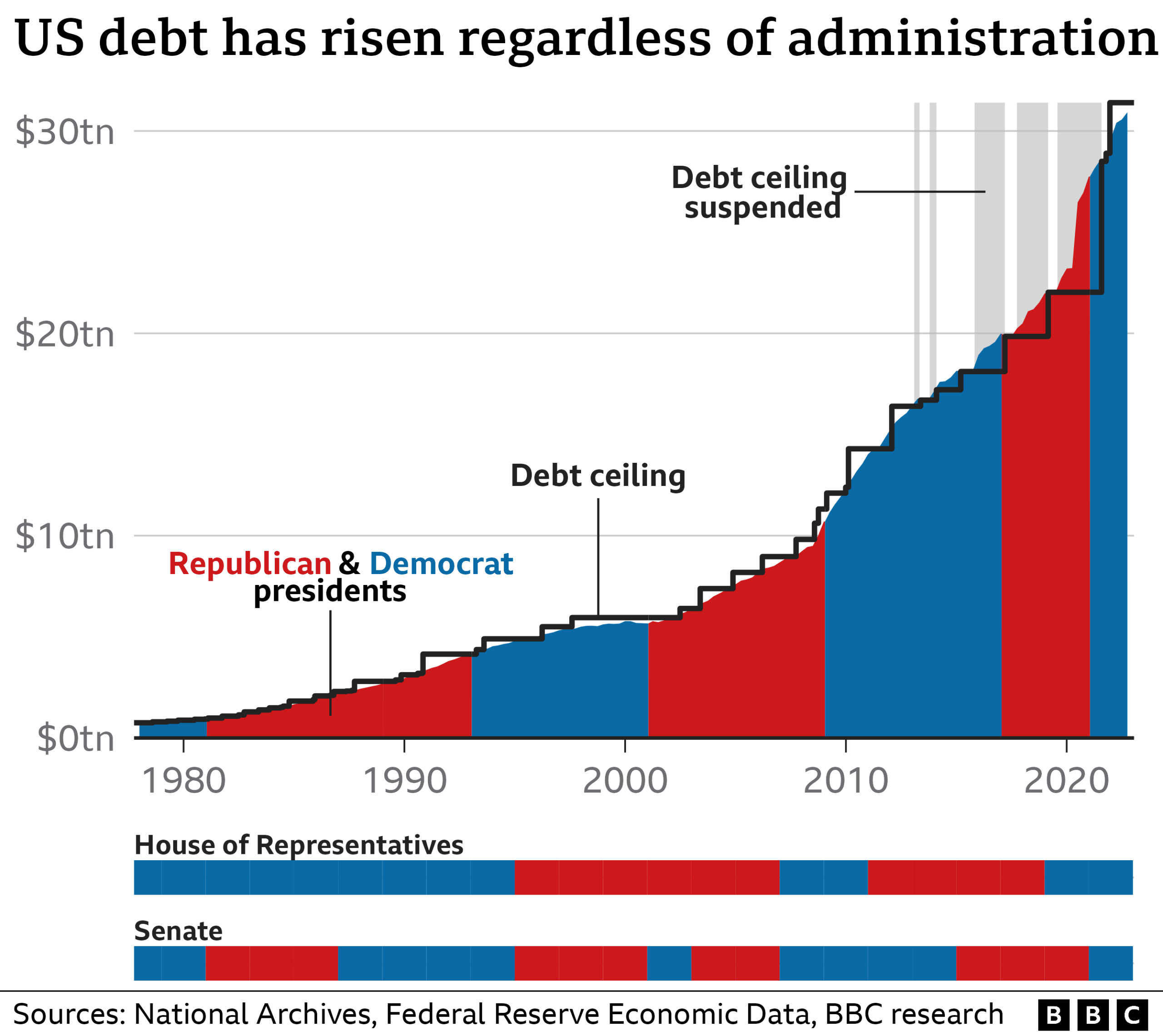

The Great Depression (1930s):

- Following the stock market crash of 1929 and widespread bank failures, fear gripped the nation. People lost trust in financial institutions and their economic future.

- Individuals and businesses drastically cut spending and hoarded cash.

- This massive drop in aggregate demand led to widespread business failures, mass unemployment (reaching 25% in the U.S.), and severe deflation. The collective attempt to save exacerbated the downturn.

- Economists like John Maynard Keynes famously argued that government intervention (public spending) was necessary to break this cycle.

-

The 2008 Financial Crisis and Great Recession:

- After the housing market collapse and the near-meltdown of the financial system, consumers and businesses became highly risk-averse.

- People paid down debt and increased their savings rates, while businesses hoarded cash rather than investing or hiring.

- Consumer spending, a major driver of the U.S. economy, plummeted, leading to significant job losses and a deep recession.

- Government stimulus packages and aggressive central bank actions were employed to counteract this lack of private spending.

-

The COVID-19 Pandemic (2020-2021):

- While unique due to forced shutdowns, the pandemic also saw a sharp increase in household savings, especially among those whose incomes were stable.

- Fear of the unknown, limited opportunities to spend (due to lockdowns), and government stimulus checks contributed to a surge in savings rates.

- While this provided a cushion for many, the initial drastic reduction in consumer spending still caused massive economic disruption, highlighting how a sudden collective pullback can cause severe damage. As economies reopened, this pent-up demand helped fuel recovery.

What Can Be Done? Counteracting The Paradox

Since individual saving is rational but collective saving can be problematic during a crisis, what steps do governments and central banks take to prevent or mitigate the Paradox of Thrift? Their main goal is to stimulate aggregate demand (get people and businesses spending again).

-

Government Intervention (Fiscal Policy):

- Increased Government Spending: The government can step in and spend money where individuals and businesses are not. This includes:

- Infrastructure projects: Building roads, bridges, and public transport creates jobs and boosts demand for materials.

- Social safety nets: Unemployment benefits, food stamps, and housing assistance put money directly into the hands of those most likely to spend it.

- Direct stimulus payments: Sending checks directly to citizens encourages spending.

- Tax Cuts: Reducing taxes leaves more money in people’s pockets, theoretically encouraging them to spend or invest.

- Increased Government Spending: The government can step in and spend money where individuals and businesses are not. This includes:

-

Central Bank Action (Monetary Policy):

- Lowering Interest Rates: Central banks (like the Federal Reserve in the U.S.) can cut interest rates.

- This makes it cheaper for businesses to borrow money for investment and expansion.

- It makes it cheaper for consumers to borrow for big purchases (houses, cars), encouraging spending.

- It also reduces the incentive to save, as returns on savings accounts are very low.

- Quantitative Easing (QE): In severe crises, central banks might buy large quantities of government bonds and other assets. This injects money directly into the financial system, aiming to lower long-term interest rates and encourage lending and investment.

- Lowering Interest Rates: Central banks (like the Federal Reserve in the U.S.) can cut interest rates.

-

Restoring Confidence:

- Often, the biggest hurdle is psychological. Governments and central banks try to reassure the public and businesses that things will improve.

- Clear communication, decisive policy actions, and visible efforts to stabilize the economy can help rebuild trust, which is essential for encouraging spending and investment.

These actions aim to break the downward spiral by injecting spending into the economy, creating jobs, and restoring the confidence needed for individuals and businesses to start spending and investing again.

The Nuance: Is All Saving Bad? The Balance Between Prudence and Prosperity

It’s absolutely critical to clarify that the Paradox of Thrift does NOT mean that saving is inherently bad, or that individuals shouldn’t save. Far from it!

- Individual Saving is Essential:

- Emergency Funds: Having 3-6 months of living expenses saved is crucial for personal financial stability.

- Retirement Planning: Saving for old age is a responsible and necessary long-term goal.

- Large Purchases: Saving for a down payment on a house, a child’s education, or a car is smart financial planning.

The Paradox of Thrift specifically applies to the aggregate effect of excessive and simultaneous saving during a severe economic downturn, especially when that saving comes at the expense of necessary economic activity.

The key is the destination of the savings:

- Productive Investment: If savings are channeled into productive investments (e.g., through banks lending to businesses for expansion, or individuals investing in stocks that fund company growth), they can fuel economic growth. This is good saving.

- Hoarding Cash: If savings are simply hoarded as idle cash (stuffed under a mattress, or sitting in a low-interest bank account when banks aren’t lending), they remove money from the active flow of the economy and contribute to the paradox.

A healthy economy needs a balance: enough individual saving for personal security and future investment, but also enough collective spending to keep businesses thriving and people employed.

Conclusion: Understanding the Delicate Economic Balance

The Paradox of Thrift serves as a powerful reminder that economics isn’t just about individual decisions; it’s about the complex interplay of millions of decisions and their collective impact. While our natural instinct during a crisis is to protect ourselves by saving, if everyone acts on that instinct simultaneously, the very act of saving can exacerbate the crisis, leading to a deeper recession, higher unemployment, and a longer path to recovery.

Understanding this paradox helps us appreciate why governments and central banks often pursue counter-intuitive policies during downturns, such as massive spending programs or extremely low interest rates. Their goal is to offset the collective desire to save and inject the necessary demand back into the economy, ultimately striving for a healthy balance between individual prudence and overall economic prosperity. It’s a delicate dance, but one that’s crucial for navigating the choppy waters of an economic crisis.

Post Comment